Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my parents

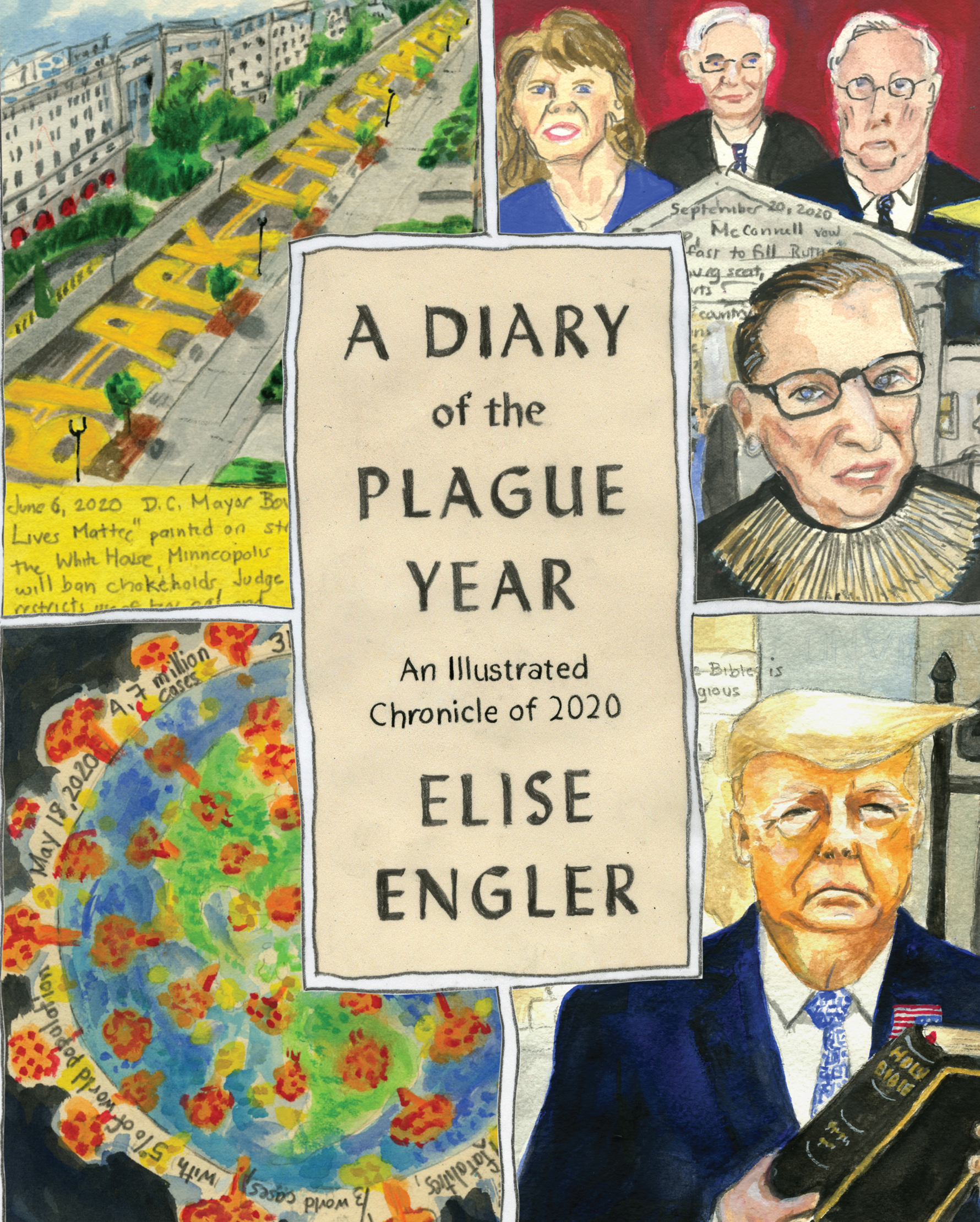

Was there ever such a year?

A global pandemic with millions dead, half a million Americans among them; a national uprising ignited by police killings of Black Americans; cities shut down, poverty soaring, a president inciting a riot to stop his election defeat, hellish wildfires, mass shootings. It was the worst year of our lives, people said, apocalyptic, unprecedented, biblical in the scale of its disasters.

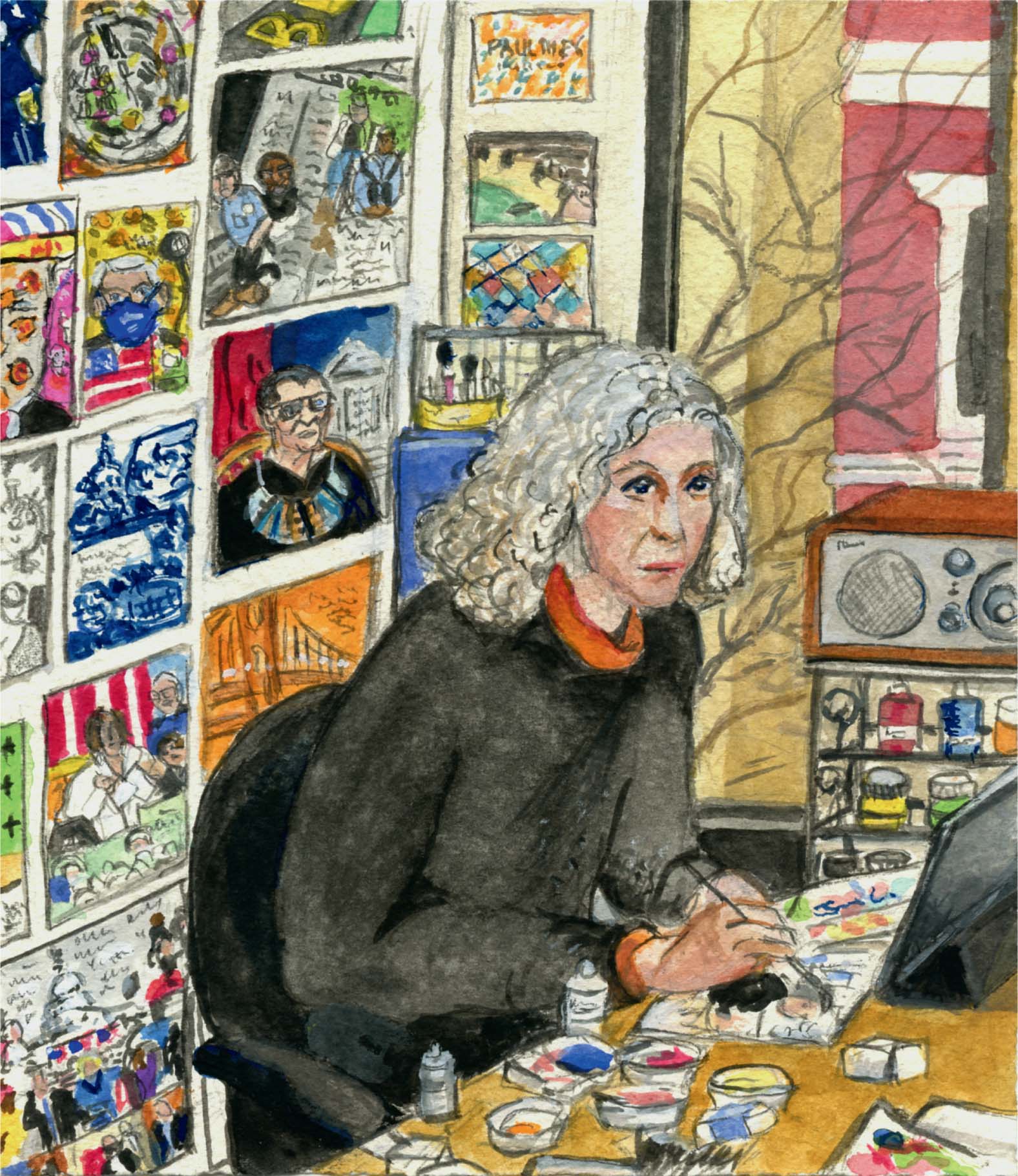

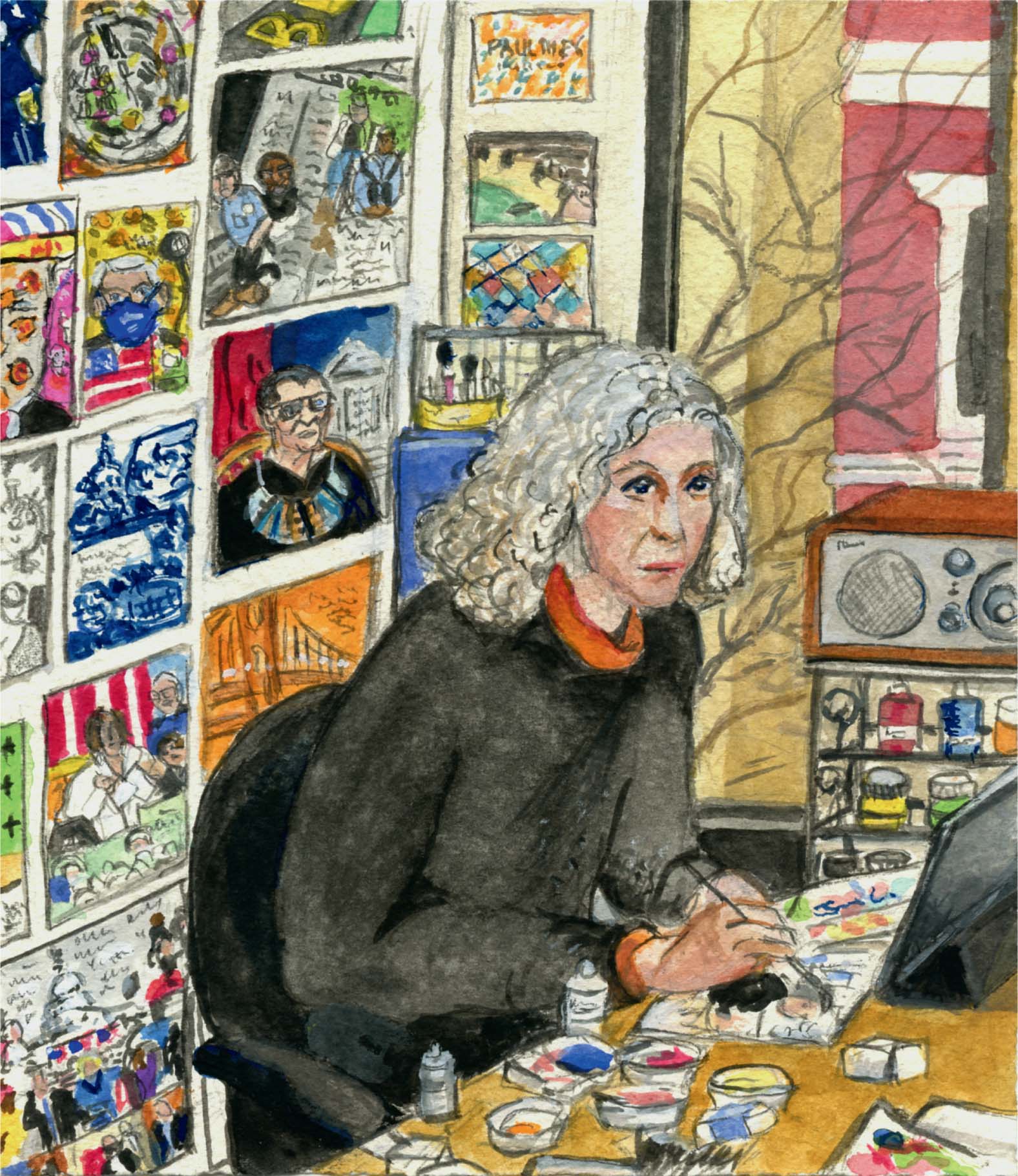

Throughout 2020 and into 2021, I painted the days headlines, making a picture of the first few news items I heard emitting from my wooden bedside radio when I woke up each morning. Viewed together here, these daily paintings, which include ordinary events along with the historic ones, ended up forming an unusual visual record of an epic, momentous year.

I did not set out to document this extraordinary time. The project that became this book began five years earlier. On November 22, 2015, I started painting a portrait of an ordinary year in American life. It would be an illustrated series called Diary of a Radio Junkie, and the idea was to do a small gouache or watercolor picture illustrating the lead headline I heard on WNYC at the start of each day. After the planned twelve months of making the paintings, I would stop and exhibit this portrait of a year.

For decades, my art had been about depicting the mundane or ordinary to create a big picture, working from the small and intimate to arrive at a greater whole. I had drawn the contents of seventy womens pocketbooks to give an intimate portrait of women who varied by race, ethnicity, class, and age. My series TaxOnomies displayed thousands of items purchased by tax dollars, from the everyday (elementary school chairs, everything on a fire truck) to the extreme (billion-dollar war planes), as a view into US government policy. Id recently finished a project showing all 252 blocks of Broadway in Manhattan, drawn on-site, day by day, block by block over a one-year period. My diary of daily headlines would be another similar assemblage, again taking place over the course of a single year.

I was not expecting to chronicle a drama. Yes, we were gearing up for a particularly belligerent presidential election, but Barack Obama had a little more than a year left in office and all seemed to be business as usual. Then Donald Trump was elected president, and I quickly realized this was not the time to stop my drawing. His would be a presidency like no other, and I wanted to continue to document it, day by day. So for the next five years, I carried on, rising at the crack of dawn to catch the mornings radio news.

Once Trump took office, there were too many outlandish and urgent headlines to be able to choose just one. Curating the news became increasingly challenging, as every day was jam-packed with possibilities. I had started with my single headline but increased that to as many as six, and I would cover local, national, and international news. Id begin at 5:00 a.m. with WNYCs twice-hourly newsbreaks and then move on to Democracy Now at 8:00 a.m. Id take notes as I listened and then choose my items: the most significant, the most underreported, and the most pictorial (sometimes one headline took care of two or three items). The same painting could include the Georgia governors race, a global Google work stoppage, and a rare species of duck in Central Park. Assembling an image from disparate parts was a compositional feat. My pencils and brushes worked to make all these pieces fit inside a small rectangular piece of paper along with the embedded headlines.

As the Trump presidency cut its operatic path through the first, second, and third years, I made portraits of the revolving-door cabinet, of world despots and dictators cavorting on the golf course, and of Trumps tweetsan oft-featured motif. There were the many faces of the Me Too movement, and the appearance of machine guns and shotguns in the tragic stories of mass shootings. I drew children in tears as they were separated from their families at the border, natural and unnatural disasters, midterm elections, impeachment hearings. Fleeting events were depicted alongside the momentous: on the day Trump insulted the venerable African American congressman John Lewis, Barnum & Bailey announced that it was closing the circus after 127 yearswhat a juxtaposition, those circus elephants and that chaotic White House.

By the end of 2019, my work formed a record of one of the most turbulent periods in our history. I didnt know that the coming year would top it.

The plague entered my drawings quietly. On January 20, 2020, COVID-19 appeared in a small portion of a pencil drawing. The rest of that days page featured the New York Times endorsement of Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar for president, as well as protests in Iraq and a flooded New York subway station. In the right-hand corner, a medically masked woman stood beneath a sign that read, in English and Chinese, Wuhan Medical, and the newspapers headline read, Coronavirus in China, cases triple as infection spreads to Beijing and Shanghai.

But it was events such as the death of basketball player Kobe Bryant, the 2020 primaries, and Democratic efforts to call witnesses in Trumps impeachment trial that drew my attention, although the coronavirus started making more regular appearances. It was on the news every few days, and then, soon, every day. On January 27, there were 2,700 cases in Wuhan, and eighty people reported dead. Now there were five cases in the United States. In early February, Trump dedicated twenty seconds to the coronavirus in his State of the Union address, but House Speaker Nancy Pelosi tearing up his speech in a dramatic show of distaste was the focus, the story that appeared over and over. The picture of masked workers producing masks was not.

After that, events moved quickly. The virus was approaching the United States, we heard; there were reports of a cruise ship with infected passengers on board being turned away by one country after another. (On the day it was finally able to dock, one of my stories was Attorney General William Barr saying, Trumps tweets make it impossible to do my job.) Only five days later, my painting showed a map of the United States with twenty-eight states painted yellow for the virus: it was spreading up and down the East Coast. The headlines on my March 12 painting read: Trump suspends all travel from Europe to combat COVID-19 (for 30 days), also announces economic measures; New York Governor Cuomo shuts down CUNY and SUNY, will institute online learning; NBA cancels season; WHO declares pandemic; Seattle closes public schools; Italy death toll jumps 30%; Iran has 10,000 cases; Harvey Weinstein sentenced to 23 years for rape and sexual assault; Supreme Court allows remain in Mexico program to continue; Bernie Sanders will stay in pres. race.