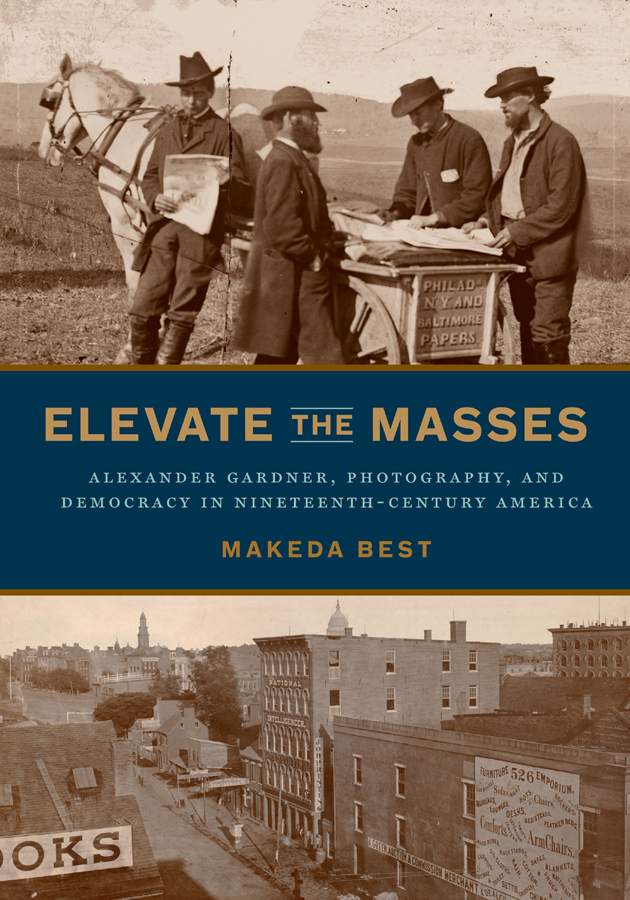

Elevate the Masses

Elevate the Masses

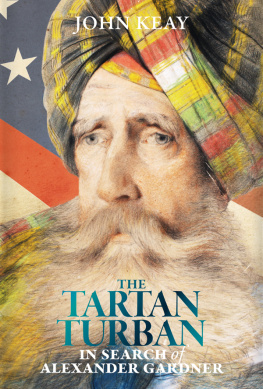

Alexander Gardner, Photography, and Democracy in Nineteenth-Century America

Makeda Best

The Pennsylvania State University Press

University Park, Pennsylvania

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Best, Makeda, 1975 author.

Title: Elevate the masses : Alexander Gardner, photography, and democracy in nineteenth-century America / Makeda Best.

Description: University Park, Pennsylvania : The Pennsylvania State University Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Examines the work of the photographer Alexander Gardner and explores transatlantic dialogues in American Civil War-era photography, demonstrating the concern over issues such as photography as a documentary form, the meaning of democracy, and the impact of industrialization on labor and social relationsProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020027354 | ISBN 9780271086095 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH : Gardner, Alexander, 18211882Criticism and interpretation. | DemocracyUnited StatesHistory19th century. | Labor movementUnited StatesHistory19th century. | SlaveryUnited StatesHistory19th century. | United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Photography.

Classification: LCC E468.9.B47 2020 | DDC 973.7 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020027354

Copyright 2020 The Pennsylvania State University

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 168021003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ansi z 39.481992.

For Sekou

CONTENTS

The titles of photographs and other artworks often vary, even within the same source. For images from Gardners Photographic Sketch Book of the War and Rays of Sunlight from South America, the title that appears printed below the image in the original texts is the one used here. Other titles of photographs and artworks derive from holding institutions.

Elevate the Masses grew out of my research as a graduate student at Harvard University. That research was made possible by a number of grants, fellowships, and assistance from curators, archivists, and librarians who shared their time, knowledge, and collections with me. My experiences working with Frank Goodyear as my mentor and within a community of young scholars as a predoctoral fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum fellowship program challenged me to ask new questions and to explore Alexander Gardners contribution from more expansive vantage points. A grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation supported key research at the postdoctoral stage. Without Robin Kelseys mentorship, I would have never believed in the expansive possibilities of this topic or fully understood the role of historical context. At Penn State University Press, I am grateful to Eleanor Goodman for her steady guidance and faith in my project. I also thank my anonymous readers, whose insightful comments led to the transformation of this manuscript.

My interest in Gardner began over a decade ago, when, as an art student at CalArts trying to make photobooks, my wonderful teacher Allan Sekula showed me a Gardner photograph and suggested that the scholarship on Gardner had yet to be written. That ten-minute conversation led to years worth of digging for me, and Allan, I wish you were here to share this moment.

For this leg of the journey, I am most indebted to the unqualified support I received from my friends and family. As they pursue the arduous and unpredictable work of research and writing, a scholar is lucky to know people who will generously offer their time, to hear frustrations or every new idea, to troubleshoot, to share laughs as well as concerns, or to inspire with their own scholarly practice. In my life, those people are Miguel de Baca, David Kim, and Jacqueline Francis. I thank my aunts and cousins for celebrating my every milestone, and my uncles for every ride to the airport and for the hours they spent for me at the post office. My dear nieces sense of wonder and curiosity replenished my own. My excitement at every theory was matched by that of my father and stepfathers, no matter the twists and turns. Before I did, my brother recognized my love of art and offered me the materials to imagine. I need to thank my mother, for always being ready and for her deep respect for the work that I do. Finally, I dedicate this book to my son. You teach me, you guide me. Your grandmother carried me into this life, but through you, my sweet and generous boy, I was reborn.

Introduction

Elevate the Masses

In the volatile society of mid-nineteenth-century Scotland new formats and platforms of criticism and dissent empowered everyday citizens to enter the public arena. Alexander Such a vantage point offers a convenient gap for inserting Gardner into the now-canonical narrative of the American photographic community at midcentury, and for understanding its trends and its economic and cultural concerns as the driving forces of his career path and pictorial interests. In early 1858, he moved his family to Washington, DC, where he continued to work as a photographer for Brady and as the manager of Bradys new satellite studio on Pennsylvania Avenue, before eventually opening a hugely successful studio in his own name.

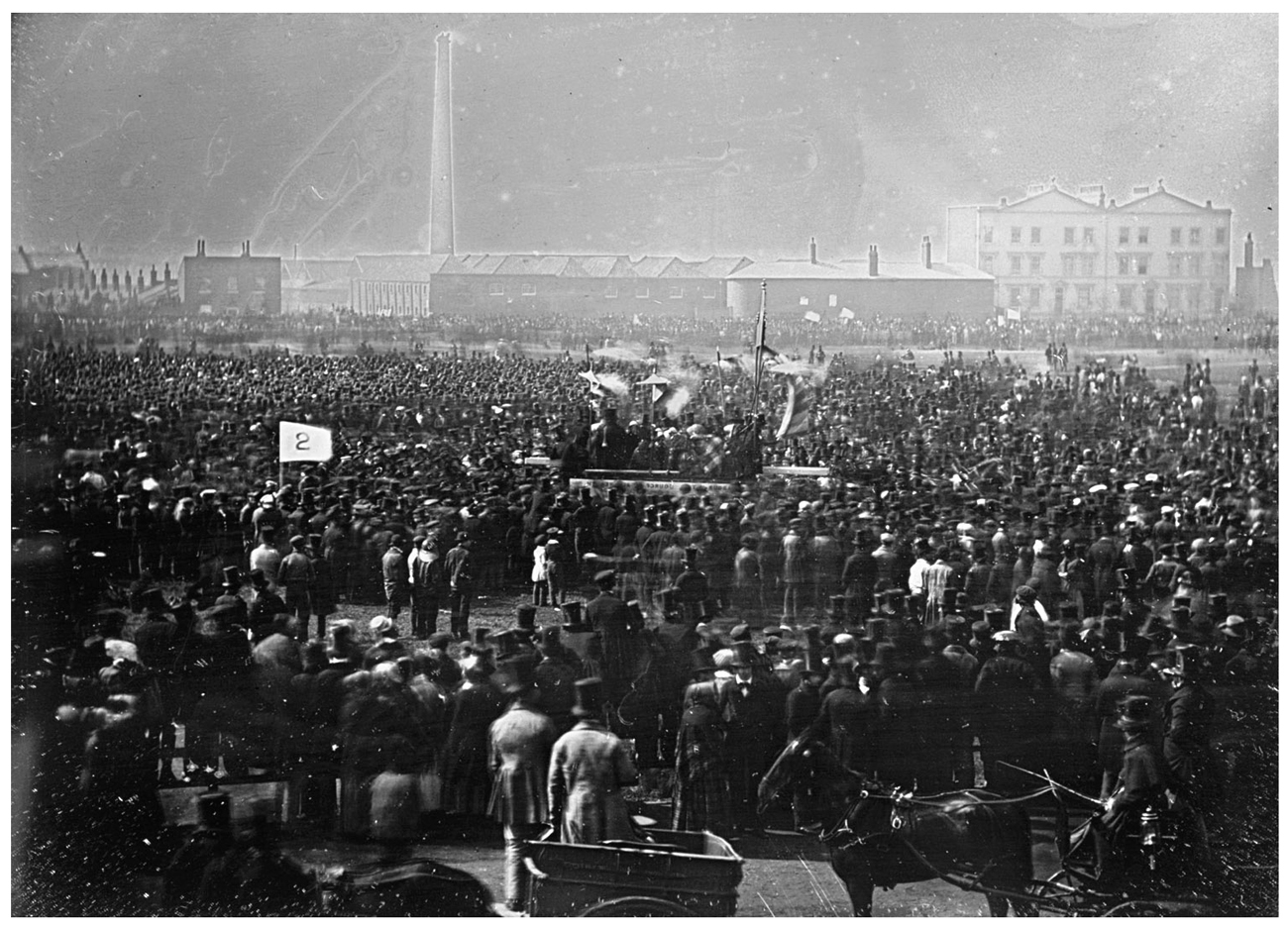

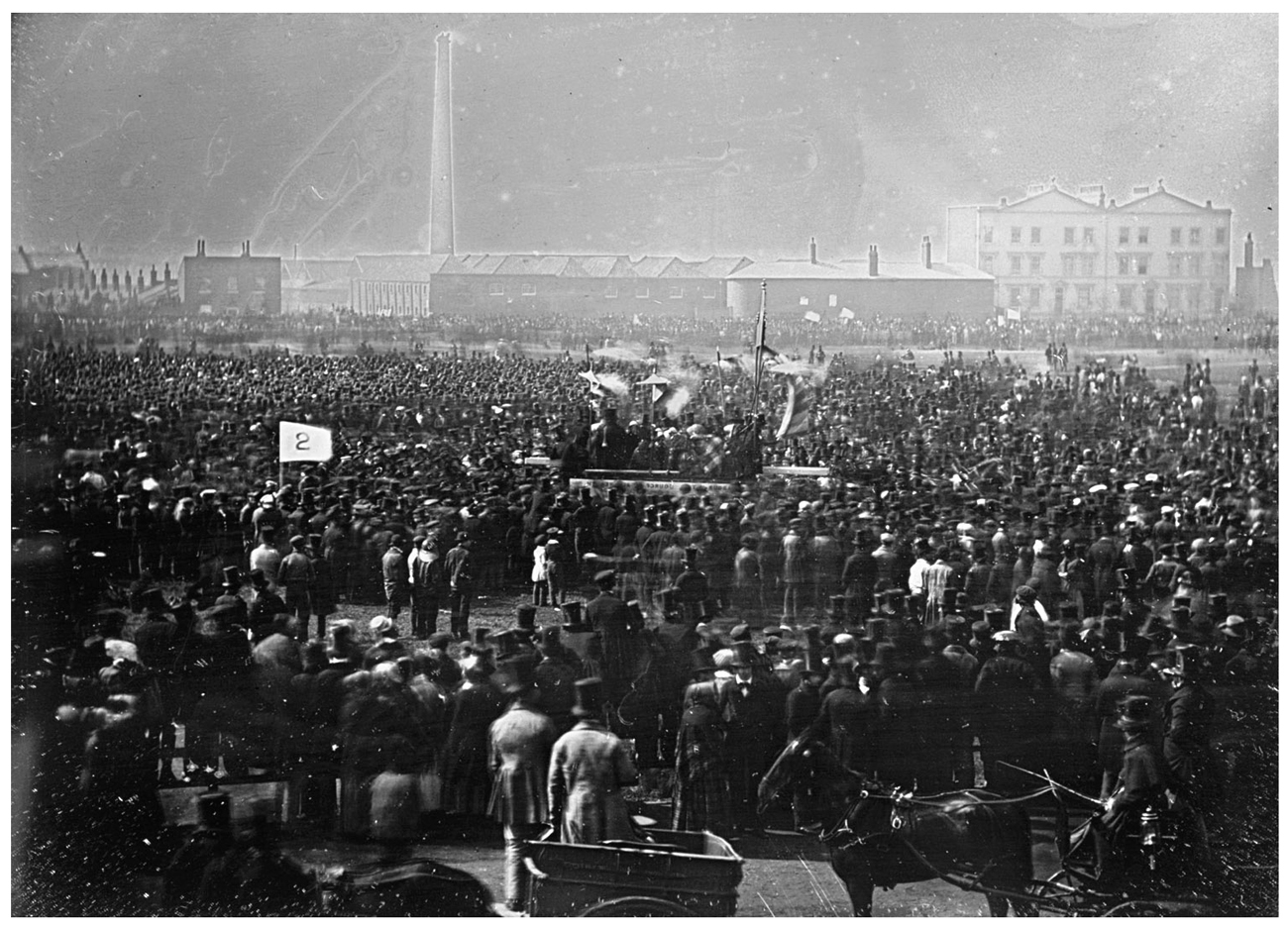

Spanning the United Kingdom, continental Europe, and the United States, a number of reform movements organized in response to economic and technical changes in the first decades of the century. The momentous events of 1848a series of popular uprisings against monarchical rule that occurred throughout Europe, beginning in Paris and eventually erupting in cities like Munich, Vienna, Krakow, and Budapestwere major catalysts for Gardners political involvement. In London, at the OConnor, claimed the petitions in support of the reforms contained nearly six million signatures, the clerks at the House of Commons rejected it, claiming that it contained fraudulent signatures and that the actual number was insufficient. This petition, the third in a series of attempts at Chartist reform, failed, like earlier efforts in 1839 and 1842. In the surviving daguerreotype of the event, the air of anticipation and the stillness of those who came to support the reform uncannily capture what many perceived as the end of a movement and the uncertainty its supporters felt.

| William Edward Kilburn, The Great Chartist Meeting on Kennington Common, April 10, 1848. Photo: Royal Collection Trust / Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019.

Despite what occurred that day, Gardner told his countrymen three years later that the cause of workers rights that had led marchers to Kennington Common endured. Civilization has, as yet, but half performed its mission, he and his team of coeditors wrote to readers of the

Gardner and his Sentinel editorial team called on the newspapers growing readership to continue to address the imbalance of power achieved by the aristocracy of land and money... [that] has, by exclusive laws and institutions, directed channels of distribution In that same address to readers, Gardner, who would become known internationally as one of the principal visual artists of the American Civil War, described himself as a longtime supporter of the independent Democratic voice, indicating that his decision to purchase the newspaper the preceding spring had been impelled by that advocacy.