Contents

Page List

Guide

Routledge Revivals

Mystics and Heretics in Italy at the End of the Middle Ages

Originally published in 1922, this translation of French historian mile Gebharts work by Hulme gives a detailed religious history of Italy in the middle ages clearly demonstrating Gebharts expertise in this area. Poetry, art and politics all centred around religion in the period studied and Gebhart identifies three key areas to be discussed; the Church in Rome, Christian concern and rationalism or secular independence whilst also focussing on famous heretics of the period including Arnold of Brescia and Francis of Assisi. This title will be of interest to students of History.

Mystics and Heretics in Italy at the End of the Middle Ages

mile Gebhart

Translated by

Edward Maslin Hulme

First published in 1928

by George Allen & Unwin Ltd

This edition first published in 2015 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1928 Edward Maslin Hulme

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under LC control number: 22023140

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-18166-3 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-315-64682-4 (ebk)

Publishers Note: The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this book, but points out that some imperfections from the original may be apparent.

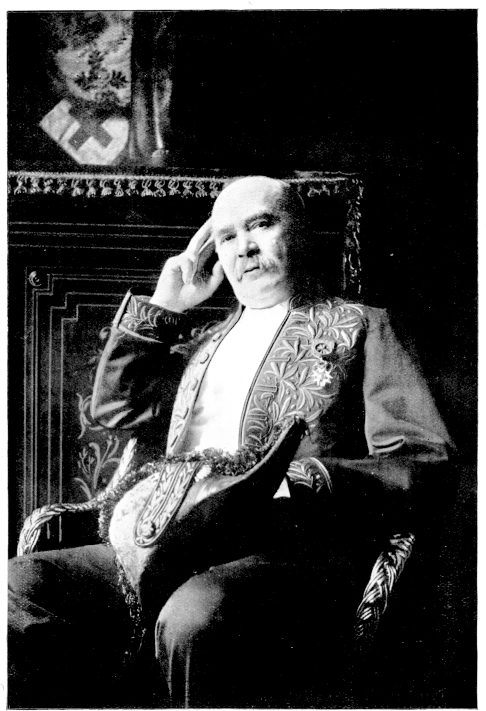

NICHOLAS-MILE GEBHART

18391908

MYSTICS & HERETICS IN ITALY

AT THE END OF THE MIDDLE AGES

BY

MILE GEBHART

TRANSLATED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION,

BY

EDWARD MASLIN HULME

This translation

First published in 1922

(All rights reserved)

CONTENTS

TO

THE MEMORY OF

MY MOTHER

ANNIE LOUISE HULME

THIS VERSION OF LITALIE MYSTIQUE

A BOOK THAT REVEALS THE SPIRIT OF AN AGE

IS DEDICATED

Youth fades, love droops, the leaves of friendship fall.

A mothers secret hope outlives them all.

ALTHOUGH the French historian and man of letters who is the subject of this brief sketch lived almost exactly the traditionally allotted term of three score years and ten, the frost of age had failed to chill the fires of his youth; his poets heart still beat high within his breast; his enthusiasms had lost nothing of their old intensity; his interests were ever widening and deepening; and his sympathies, more inclusive than ever with the passing of the years, had but mellowed in the autumnal glow. To have devoted half a century to the writing and teaching of history (for though he sat in a chair of literature he emphasized the historical aspect of his subject), to have written many exquisite historical sketches, one ambitious historical novel impregnated with the authentic spirit of its time, and at least two important historical works unsurpassed in insight and synthetic power in their respective fields, and, in addition, to have created in the minds of many students an understanding of the significance of two great periods in the story of the human past, and to have enkindled in their hearts a deep and abiding love for those times, for the noble men who lived in them, and for the beauty of the art that still gives voice to their ideals, to have done all this, and without stain in the doing, is surely an enviable accomplishment and one well worthy of commemoration. Yet thus far only one of his books has been done into English, and that a minor one; in no paper published in the English-speaking world did his death evoke more than a brief paragraph; and in his own country he seems to be generally underrated as a writer of mere exquisite miniatures rather than esteemed as a scholar of insight and learning as well as of grace.

Nicholas-mile Gebhart was born in 1839 at Nancy, the old capital of Lorraine, which at that time was not as prosperous and animated as it afterwards came to be, but which could nevertheless boast a grace now vanished. The men of Lorraine, so one of their number has said, have three ruling passionsthe army, art, and the forest. Gebhart and his two brothers, although of Alsatian parentage, personified these three passions. The eldest was a soldier and rose to the rank of general; the youngest became a commissioner of forests; and the second was the man of letters whose life we are to narrate and whose work we are to estimate.

The sensitive and imaginative boy proved to be an excellent pupil in the public school at Nancy, and among the prizes he won was a copy of the Journey from Paris to Jerusalem. No other writer made a deeper impression upon French literature in the nineteenth century than Chateaubriand. His extraordinary faculty for the description of nature, his exquisite sense of style, his impassioned eloquence, the richness of his imagination, the ardour and the violence of his passions, his sombre fidlit pour les causes tombes and, above all else, the touch of Celtic magic that distinguishes so many of his pages, enchanted the child Gebhart and induced him to dream, beneath the pale sky of his northern town, of the olive and the oleander, of purple seas and purple mountains, of distant lands where the temples are fallen and where the silence of the long summer days is broken only by the hum of the insects. The passion he conceived for Chateaubriand never left him. And, as was the case with little Pierre in Le Lys Rouge from these school days dated a taste for sonorous Latin and elegant French which he never lost despite the example, and, indeed, if not even the counsel, of many of his more famous contemporaries. In due time he continued his studies at Nancy under the newly-established Faculty of Letters, of which five of the professors had been members of the French School at Athens. When he received the degree of Bachelor of Letters his father, who was himself a provincial magistrate, sent him to Paris to study law. There he became a lawyer, and, although it is not recorded that he ever pleaded a case, he long maintained a nominal connection with the profession.

But even while preparing for his degree in law, young Gebhart did not neglect letters. He frequented the Sorbonne and was in particular attracted by the lectures of M. Saint-Marc Giradin. One day, in speaking of La Fontaine, the famous professor vigorously denounced the idle and improvident grasshopper. The next week he read a letter of protest, received, he explained, since the last lecture, which, pleading the cause of the light-hearted insect, was signed A Grasshopper of the Latin Quarter. So delighted were the auditors with the cleverness of the reply that they requested the name of the author. Thus did Gebhart enjoy the intoxication of a first literary triumph. Strange that a defender of