BASELINE CO. LTD

All modification and reproduction rights reserved internationally.

Unless otherwise stated, copyright for all artwork reproductions rests with the photographers who created them. Despite our research efforts, it was impossible to identify authorship rights in some cases. Please address any copyright claims to the publisher.

1. Self Portrait(detail of the

Adoration of the Magi), 1500.

Tempera on wood, 111 x cm .

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

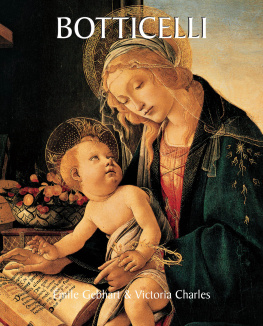

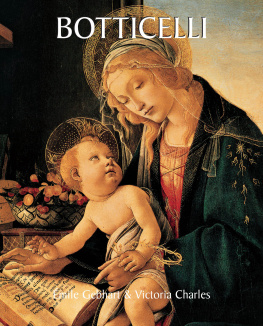

2. Virgin and Child with Saint John

the Baptist as a Child (detail), c. 1468.

Tempera and oil on poplar, 90.7 x cm .

Muse du Louvre, Paris.

Botticellis Youth

and Education

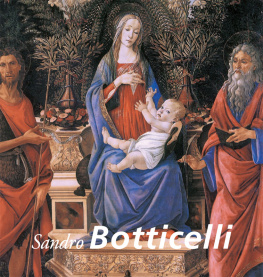

3. Sandro Botticelli (?), Virgin and Child

with Saint John the Baptist, c. 1491-1493.

Tempera on panel, 47.6 x 38.1 cm .

Ishizuka Collection, Tokyo.

4. Virgin and Child with Two Angels, c. 1485-1495.

Tempera on panel, diameter: 32.5 cm .

The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago.

Alessandro di Mariano Filipepi, also known as di Botticello in homage to his first master, and Sandro Botticelli to those who knew him, was born in Florence in 1445. Even though Vasari asserts he died in the city-state of Florence in 1515, he passed away on May 17 th , 1510. Shrewd and highly alert, he was endowed with a certain aristocratic grace, a typical child of the sophisticated class of Florentines. The rigid traditions of the old medieval Commune might well have restricted him to his professional guild or his quarter, or could have tied him to some modest manual occupation. He thus would have had a goldsmiths workshop or a pharmacy in the shadow of his fathers house, or would have sold Psalters and rosaries on the Ponte Vecchio. On Sundays he might have sung endless Laudes amongst his companions of the Dominican clergy, and on occasion he would have donned his blue, black, or grey penitent cape and a yellow wax candle and would, without sadness, have followed the mortal remains of some neighbour to the nearest Campo Santo. A very narrow and humble destiny, which Florentines of the past had accepted indifferently, while the city, according to Dante sobria e pudica, lived happily in the untouchable sphere of its worldly traditions. But from the middle of the 15 th century, the bonds that tied the citizen and curbed his will and the fancies of his ambition began to crack. The Renaissance gave birth to a creature full of inclinations, the Individual, who now escaped the olden discipline. Encouraged by the Church, adulated by tyrants, republics, or art patrons, the quintessential Florentine art rose above the Arti Maggiori, higher still than the bankers, lawyers, wool or silk weavers. It was the art of the painter or sculptor, an aristocracy amongst the princedoms of the Quattrocento, a glory of which young boys were dreaming longingly as soon as they beheld and admired Giotto at Santa Croce, Masaccio at Carmine, Fra Filippo Lippi at the Cathedral of Prato, or Donatello at Orsanmichele.

Now the passion for beauty possessed the soul of Italy and ruled supreme over Florence. There was not a palace, not a church, not a monastery that was not a feast for the eyes and a solemn reminder of the Christian conscience in a dashing play of colours, magnificent garments, the grave demeanour of the figures and their postures, and the display of the most dignified scenes from the Old Testament or the Gospel.

An incessant popular pilgrimage brought citizens of the Mercato Vecchio and the farmers of the contado to those beautiful works of art every day. Here they found the image of their faith, the edifying liturgical dramas of the Rappresentazioni sacre: the stable of Bethlehem with the ox and the ass; the Wise Men prostrated in front of the manger, clad in purple and ermine, holding the golden incense burners; the painful episodes of the Passion, Jesus, covered in blood, crowned in thorns, crucified between two thieves, resurrected, victorious over death. It was here they greeted the patron saints of their city, village, parish, or friary. As often as ten times a day, a Florentine citizen would find himself lifting his cap in front of an icon of Saint John, clad poorly in a sheepskin, carrying his frail reed cross. Or maybe this citizen stopped at some hospital portico, or a cemetery pavilion, or in the courtyard of a rich Guelph mansion; and wherever he went he would be confronted with the symbols of his public life, even with a vision of his own dying hour. He would see processions and grand entrances of lords, tournaments and banquets, the trumpet of Judgment Day and the pale dead rising from their graves.

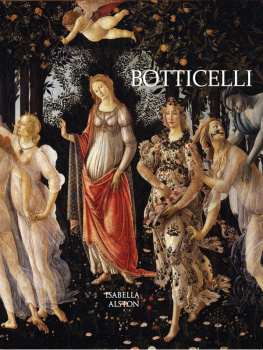

5. Virgin and Child withSaint John

the Baptist as a Child, c. 1468.

Tempera and oil on poplar, 90.7 x cm .

Muse du Louvre, Paris.

6. The Virgin Adoring the Child,

1480-1490. Tempera on panel,

diameter: 58.9 cm . National Gallery

of Art, Washington, D.C.

7. Sandro Botticelli and assistants,

The Virgin and Childwith Saint John

Adoring the Child, c. 1481-1482.

Tempera on panel, diameter: 95 cm .

Musei Civici di Palazzo Farnese, Piacenza.

8. The Annunciation, c. 1495-1500 (?).

Tempera on panel, 49.5 x 61.9 cm .

Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow.

From the 13 th century onward, painters became the pride of Florence. Cimabues grand Byzantine Madonna at Santa Maria Novella, so rigid still, and of such a sullen countenance, nonetheless stunned the dilettanti of the year 1260. When Charles I of Anjou crossed Tuscany on his way to Naples, the magistrates honoured the brother of Saint Louis between all the festivities and entertainment by taking him to visit Cimabues workshop in a garden near the Porta San Piero. All the noblemen, the high bourgeoisie, and the genteel ladies accompanied the French prince with such exclamations of joy that this quarter has since been called Borgo Allegri. To the sound of trumpets and bells, the Madonna was then taken from the painters house to the Rucellai chapel in a very solemn procession. Over the course of the 14 th century, the writings of Boccacio and Sacchetti began to reveal the freedom that the Florentine spirit gave to craftsmanship, to adventures and miseries, to the artists skill and wit, to Giottos jests, and to the practical jokes of the incomparable second-hand artist Buffalmaco. From the middle of the 15 th century, Florentine art itself assumed a national purpose. The patronage of the Medici, from Cosimo the Elder to Lorenzo the Magnificent, elevated the social standing of sculptors and painters who dedicated themselves to the embellishment of patrician life. In fact, all the princes and city-states of Italy borrowed Florences painters and sculptors, who were sent as missionaries of its genius to all the schools of the peninsula. The artists were received everywhere enthusiastically, regardless of their origins: Sixtus IV invited them to decorate the Sistine Chapel, Alexander VI left the rooms of the Vatican to the superb brush of the Umbrian Pinturicchio, who displayed the drunken revels of the Borgia without shame. The rigid pride of Julius II never bent except for when he faced the one and only Michelangelo. Leo x was seen kneeling and crying at Raphaels deathbed