Peter Grose began his working life as a journalist for the Sydney Daily Mirror before becoming the first London correspondent of The Australian. He switched from journalism to literary agency, setting up Curtis Brown Australia, then the first literary agency in Australia and now the biggest. After moving to the London office of Curtis Brown, where he continued as a literary agent, he joined the London publisher Martin Secker & Warburg as publishing director. In his retirement he returned to his first love: writing. He is the author of three best-selling history books. He is also the proud holder of British, American and Australian private pilots licences, and has flown all over Australia, Europe and the United States in single-engined aircraft. His most recent book is Ten Rogues. He lives in France.

This edition published in 2021

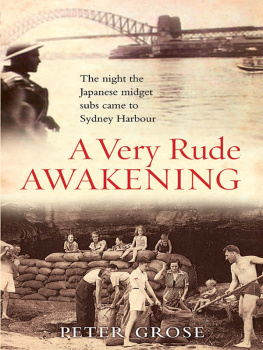

A Very Rude Awakening first published in 2007

An Awkward Truth first published in 2009

Copyright in this collection Peter Grose 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Every effort has been made to trace the holders of copyright material. If you have any information concerning copyright material in this book please contact the publishers at the address below.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone:(61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web:www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 9 781 76106 664 1

eISBN 9 781 76106 346 6

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

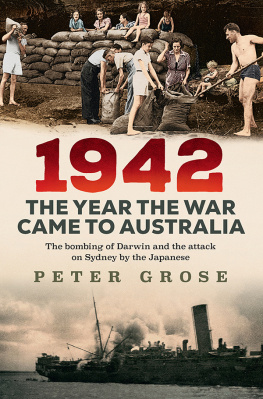

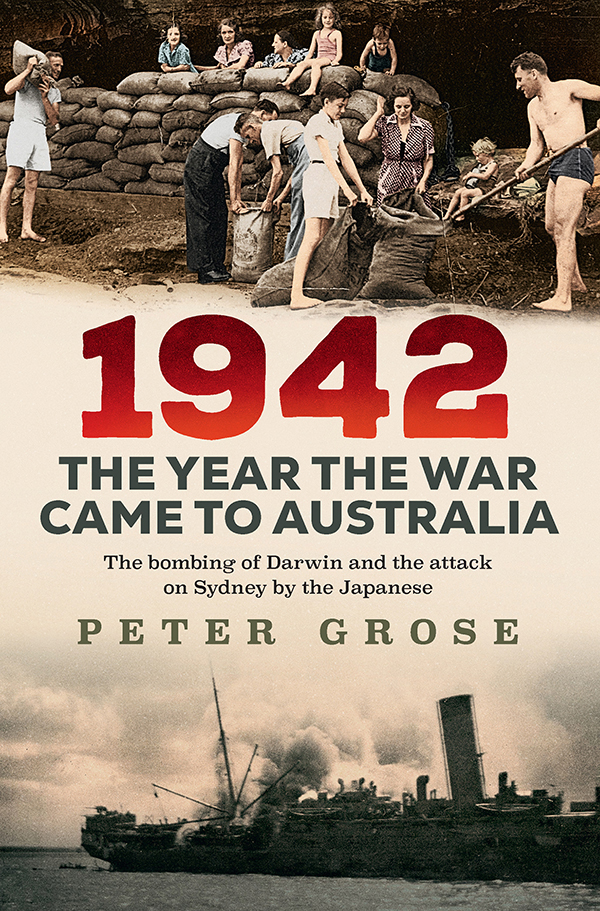

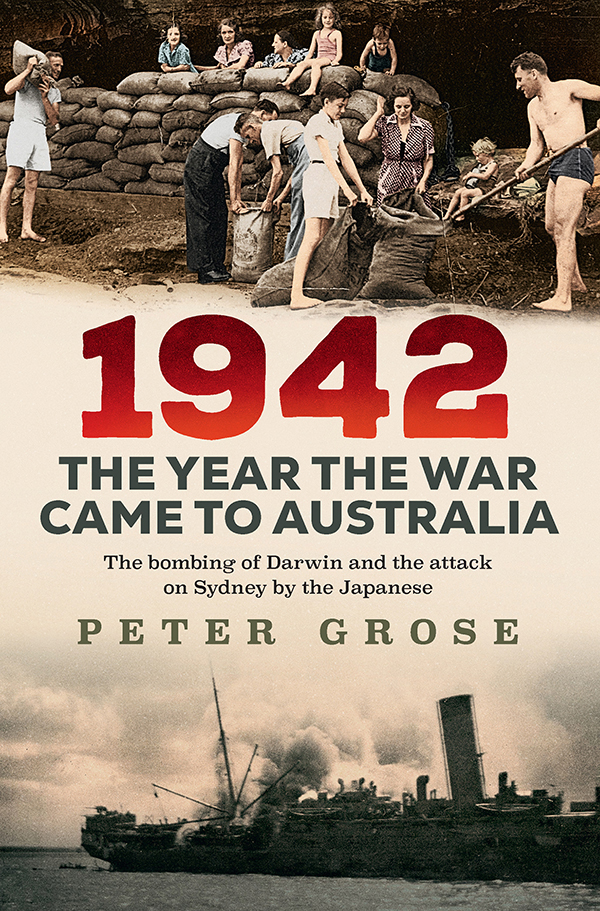

Cover design: Luke Causby/Blue Cork

Front cover photographs: (TOP) Lionel Lindsay (bottom right), with his family (wife Phyllis and children Anne, Margaret and Geoffrey) and neighbours building an air-raid shelter near Parsley Bay, Sydney Harbour, during World War II. Courtesy of the Lindsay family. (BOTTOM) MV Zealandia in Port Darwin in the first air attack, J. Davey/AWM P03707.004

For Anouchka and Tamara, who can both write their Dad under the table

Bloody Darwin

This bloody towns a bloody cuss,

No bloody trams, no bloody bus,

And no one cares for bloody us,

Oh bloody, bloody Darwin.

The bloody roads are bloody bad,

The bloody folks are bloody mad,

They even say you bloody cad,

Oh bloody, bloody Darwin.

All bloody clouds and bloody rain,

All bloody stones, no bloody drains,

The Councils got no bloody brains,

Oh bloody, bloody Darwin.

And everythings so bloody dear,

A bloody bob for bloody beer,

And is it good? No bloody fear,

Oh bloody, bloody Darwin.

The bloody flicks are bloody old,

The bloody seats are bloody cold,

And cant get in for bloody gold,

Oh bloody, bloody Darwin.

The bloody dances make me smile,

The bloody band is bloody vile,

They only cramp your bloody style,

Oh bloody, bloody Darwin.

No bloody sports, no bloody games,

No bloody fun with bloody dames,

Wont even give their bloody names,

Oh bloody, bloody Darwin.

Best bloody place is bloody bed,

With bloody ice on bloody head,

And then they say youre bloody dead,

Oh bloody, bloody Darwin.

Anon.

(Soldiers doggerel, circa 1941)

The birth of Australia as a nation took place on 25 April 1915, so we are told, when Australian troops stormed ashore on the beaches of Gallipoli. For the first time, the mostly British settlers in Australia saw themselves as Australians, not as scattered British colonists in an inhospitable southern wilderness. If that is true, I would argue that Australia became an independent nation on 19 February 1942, when the Japanese bombed Darwin.

Consider the evidence. The first two years of the Second World War were fought exclusively in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Australia was then a British Dominion, part of the British Empire. When Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, the Australian prime minister, Robert Menzies (a lawyer), thought Australia was legally bound to join the war on Britains side. Menzies exact words, in a radio broadcast to the nation, were: Great Britain has declared war upon [Germany] and as a result [my emphasis], Australia is also at war.

The Royal Australian Navy was simply merged into Britains Royal Navy, under British command. In 1941 Menzies felt obliged to move to London for a few months, while he held long discussions with Churchill on the conduct of the war, and took part in some British War Cabinet meetings. In his absence, his political enemies plotted his downfall, and they lay in wait for his return. On 28 August 1941 Menzies was forced to resign. After a brief period of turmoil, on 3 October 1941 the opposition Labor Party was asked to form a government, with the untried John Curtin as the new prime minister.

Curtin saw things differently from the anglophile Menzies. Japan had entered the war on 7 December 1941, when it attacked the American Pacific Fleet at anchor in Pearl Harbor. Australia was now directly threatened. The war was no longer confined to Europe, North Africa and the Middle East; it had spread to the Pacific and Australias doorstep. Less than three weeks after Pearl Harbor, Curtin stood Australian foreign policy on its head. In an article in the Melbourne Herald dated 27 December 1941, he wrote: The Australian government regards the Pacific struggle as primarily one in which the United States and Australia must have the fullest say in the direction of the democracies fighting plan. Then came the killer punch: Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.

This produced a gasp of shock around Australia. In an editorial, the Sydney Morning Herald called the article deplorable (while pinching its nose and reprinting it in full). Australia looks to America, not Britain? Free of any pangs? It sounded like madness. But Curtins radical thinking was well vindicated seven weeks later, on 15 February 1942, when Britains impregnable Singapore base fell to the Japanese, opening a gateway to Australia. It was now clear that Britain couldnt or wouldntthe difference was immaterialdefend Australia.

Four days later the Japanese struck directly. The same carrier force that had devastated Pearl Harbor now wreaked similar havoc on Darwin, dropping more bombs there than they had dropped on Pearl Harbor, and killing more civilians than they had killed at Pearl Harbor.

There could be only one conclusion: Curtin was right. Australia had to fight its own battles, form its own alliances, and look to its own interests. Independent Australia was born that day. The events in the pages that follow are too terrible to call for any celebration, but if Australians want to mark an anniversary of their independence as a nation, 19 February is the day to do it.

Next page