This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1989 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

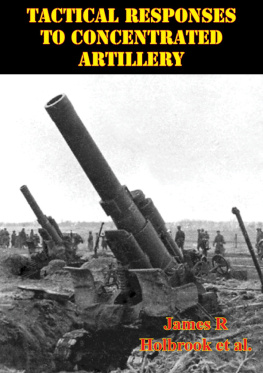

CSI REPORT

NO. 13

TACTICAL RESPONSES TO CONCENTRATED ARTILLERY

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

PREFACE

The focus of this study is on how the armies of different nations countered the threat of massive concentrated artillery and/or other types of preparatory fires. Not all were successful, and the reasons for the success or failure of each army provides the contemporary military commander an opportunity to learn from his predecessors and benefit from their hard-learned lessons.

Note: In this publication, when the masculine gender is used, both men and women are included.

INTRODUCTION

The Western Front in World War I provides the classic case of a response by defending armies to concentrated artillery fire. This is the standard to which even conflicts as far removed as the recent Iran-Iraq War are compared. All the methods available to counter heavy artillery concentrations were present in the Great War: fortification, armor, dispersion, constant movement, deception, counterfire, and ground attack on the gun line. Yet the Great War did not start out as an artillery war. Initially, the armies that became locked in combat on the Western Front had seen artillery only as an auxiliary to a battle between bodies of infantry and cavalry. The scale of artillery used in earlier battles was modest compared to that of later struggles where the number of artillerymen engaged could approach the infantry strength as close as 8 to 10. Prewar tactical emphasis was on light quick-firing artillery capable of supporting forces fighting in the open, creating and protecting flanks, and maintaining the advance of maneuver forces. Only the Germans, who had to overcome Belgian frontier forts, invested much in heavy artillery. Tactical doctrine was offensive, suitable it was thought, to the spirit of the contending nations. It was not, of course, suitable to the conditions of war the two sides found on the World War I battlefield.

The contending armies were forced to ground at first, not by the artillery, but by the fire of magazine rifles and the limited number of machine guns available at the start of the war. By the end of 1914, the armies faced each other across a no-mans-land from fairly shallow trench systems that extended in breadth from the Alps to the English Channel. It was then that artillery, particularly indirect artillery of medium and heavy calibers, came into its own. Artillery became the means to open new flanks by blasting penetrations into enemy trench systems. For the defender, it became the means of protecting or covering flanks. The attackers artillery was required to suppress the defenders direct-fire systems, to cut the defenders wire entanglements that denied access to his trench lines, to destroy the defenders positions, to block relief by his reserves during an attack, and to neutralize the defenders artillery. Knocking out the defenders guns would prevent him from bombarding the attackers artillery, his command and control, the assaulting infantry, and those reserves that would concentrate on the attackers side of no-mans-land to sustain an offensive once launched. On 1 July 1916, British units suffered significant numbers of casualties on the way to their jumping-off point.

The creation of great concentrations of artillery, capable of breaking a pathway into enemy trench systems, forced a change in defensive tactics. Both sides moved to deeper defensive systems, with German Colonel Fritz von Lossberg developing what has become the classic concept of elastic defense. the random and disorganizing losses that accompanied any advance. Their withdrawal could be blocked by a standing barrage, and they could be destroyed out of sight of their own supporting fires.

Conceptually, the scheme of defense called for sighting a security zone on the military crest of a piece of high ground. Since the Germans had occupied about one-third of France in their initial advance, they could select a good defensive line and then withdraw to it, which they did on a large scale at least twice during the war. Such a withdrawal was clearly more difficult for the Allies. The defender would set up his forward line of defense on the reverse slope of the terrain feature, out of direct observation and free from direct or observed fires. Even this line was designed only to resist local attacks, not general offensives. Behind this line was a zone of machine-gun posts and/or successive trench lines whose purpose was to support the forward defense line and to break up the coherence of attacking forces strong enough to overcome the forward defense. This zone was deep enough to draw the attacker out from under his own artillery support, and it led to a final line of resistance behind which were fresh counterattack troops whose purpose was to apply that flashing sword of vengeance, which Carl von Clausewitz saw as the source of the greater strength of the defensive form, hopefully to restore the entire defensive zone. The counterattack was the most important feature of the elastic defense, and it remained a characteristic of German defensive fighting through World War II. Interestingly enough, reserves designated for the counterattack were committed under the command of the officer responsible for a zone of the defensive system notwithstanding the relative rank of the commander of the counterattack force versus the commander of the defensive zone. This provided for the ability to respond before the attacker could knit his own defense together when the advance was stopped.

To deal with this sort of defensive zone, the armies armed their maneuver forces with far more effective accompanying weapons and decentralized their tactical execution. The combination of infiltration tactics and limited objective attacks could minimize the effect of the elastic defense and increase the cost to the defender, but it could not lead to the strategic or operational success necessary to bring the war to the end. The war of attrition, always the consequence of an inability to win a decisive victory or find a basis for negotiation, continued. This proved to be the case no less on Okinawa and in Korea than on the Somme.

In World War II, several of the World War I problems were corrected. Operationally, tactical air support provided compensation for the immobility of an attackers cannon artillery. Mechanized forces, protected from small-arms and machine-gun fire, using infiltration tactics and now controlled by radio, could break through an enemys defensive zone and exploit into the operational depths, disrupting the coherence of the whole defense until the defender too adapted to the requirements of mechanized warfare, learned to control his own reserves (mechanized and air) by radio, and recognized that defensive zones would have to be deepened to correspond to the geometric increase in mobility inherent in the shift from foot to mechanical traction or even aerial insertion. For all that, the tactical problem remained very much the same: absorb the enemys preparation fires, break up his attack, counterattack to destroy his forces, and restore the defense. While the decisive defensive battle might now be fought by operational reserves upon whose success or failure the entire theater defense might rest, this was so largely because the defensive fighting in secondary zones remained very much what it had been in World War I. Modern armies, dependent on umbilical cords from their rear, can move as self-sustained forces only for limited periods of time. The immobile mass, or fixing force, protects the movement of the means of sustainment from interference by enemy ground combat units. By its presence, it requires the concentration of the breakthrough force on limited axes. In World War II, the opposing infantry divisions provided the framework for the mobile battles, and to the extent that forces will continue to be required to hold ground in modern defensive combat, they will continue to do the same.