Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

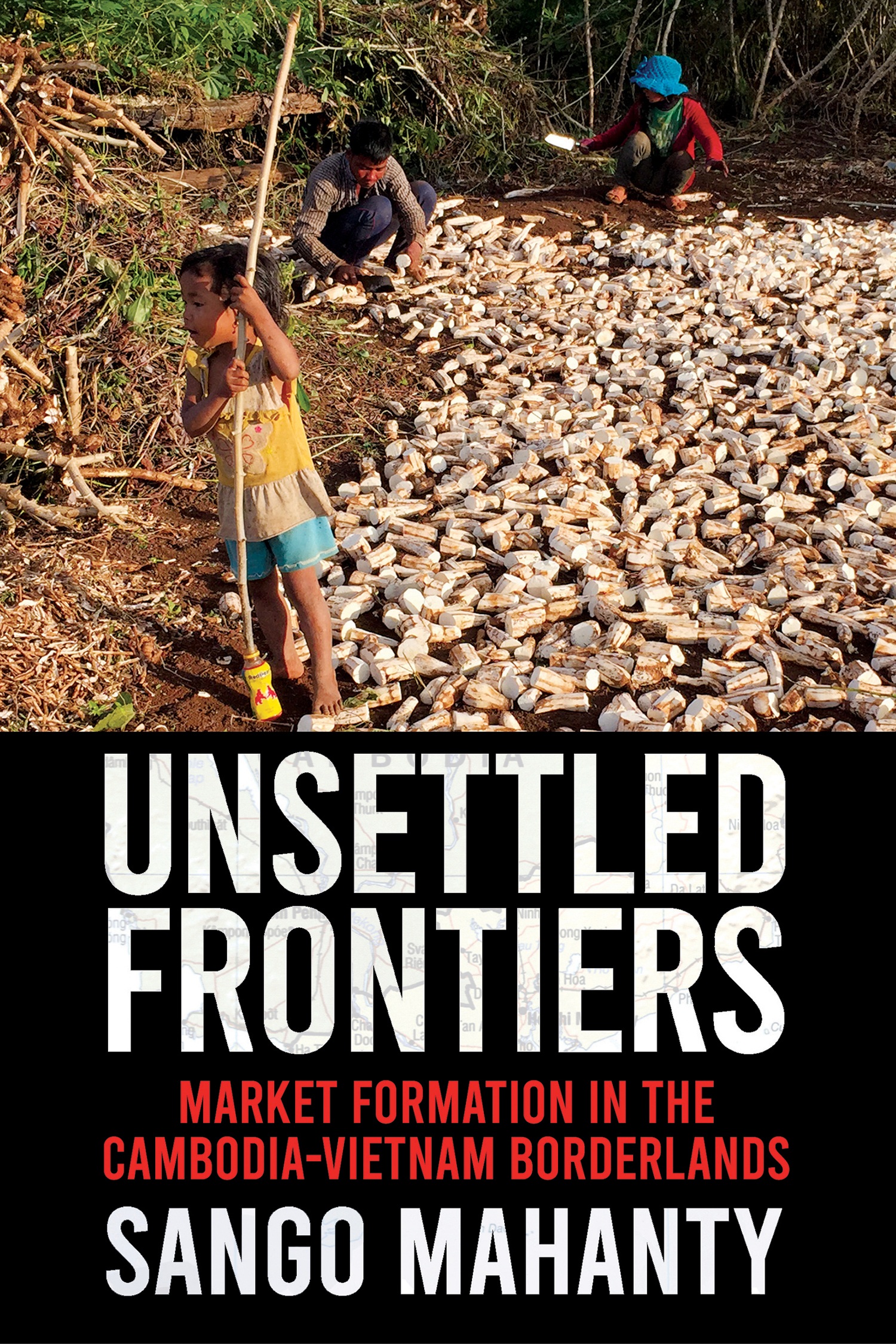

UNSETTLED FRONTIERS

Market Formation in the Cambodia-Vietnam Borderlands

Sango Mahanty

SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM PUBLICATIONS

AN IMPRINT OF CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESSITHACA AND LONDON

For Matthew, Nisha, Kiran, and Ashwin

Contents

Preface

My engagement with Cambodia and Vietnam has followed a winding path. I first worked in these two countries between 2005 and 2007. As an analyst with the Bangkok-based Centre for People and Forests, my role was to engage with my Cambodian and Vietnamese counterparts to document early lessons from the community forestry projects that had started to emerge there.

The experience sparked my deep interest in this regions history and challenges. After I joined the Australian National University in 2007, I found opportunities to continue my research there. During 20092012, I collaborated with the Vietnamese Institute of Policy and Research in Agriculture and Rural Development to study how craft villages in the Red River Delta were coping with toxic levels of pollution. In 2011 I studied the prospects for community-run timber extraction in Mondulkiri, Cambodia. Then, during 20122014, I led a collaboration that studied the social entanglements of forest carbon schemes in mainland Southeast Asia (ARC DP120100270), where my field efforts focused on a scheme in Mondulkiri. It was during this last project that I witnessed the dramatic changes sweeping this province, arising from its transborder trading networks and crop boomsespecially for cassava. This inspired my more detailed research on cross-border commodity networks, with the support of an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (20142018, FT130101495).

Although my analysis in this book is strongly informed by my Future Fellowship research, it was these earlier engagements that created the foundations. They grew my knowledge about the histories, landscapes, political economy, and state-society relations of these two countries. This earlier work also enabled me to study the relevant languages, which I commenced in 2009 for Vietnamese and in 2012 for Khmer. I reached a basic proficiency in these two languages but have always worked closely with research assistants and interpreters during fieldwork (see below). Upland communities are not always fluent in dominant national languages, especially the elderly, so I sometimes engaged a local Bunong interpreter.

My long-standing networks in the two countries enabled me to gain the red stamps (S. Turner 2013) that are so important in studying a sensitive border region. In both countries my host institutions facilitated the relevant national- and provincial-level permissions. Yet the additional requirements of a borderland study set me on a steep learning curve. During my first visit to a Vietnamese border crossing in T y Ninh, it emerged that our portfolio of permission letters was short on one crucial letterfrom the provincial military office. Military officials quickly surrounded our small research team and instructed us to leave the area. We returned to the provincial capital, taking another week to organize the missing documentation before we could return to our field site. A further complicating factor with Vietnamese approval processes was the need for documents to mention all the localities where the researcher would godown to the commune level. Yet the networks that I was studying traversed localities in a very fluid way. I quickly learned to routinely include most border communes and districts in my targeted provinces in these approval applications so that I could flexibly follow traders and other network actors.

Aside from the complications of official approvals, scholars of this region acknowledge that foreigners often face additional constraints during field research (Sowerwine 2013). I was the subject of official surveillance, especially in Vietnams border districts and during visits to factories. In contrast, discussions with traders sparked less interest from the authoritieseven though traders were among the most open and informative sources on such issues as illicit trade and corruption. Official surveillance usually eased over time, but overall this did mean that my data collection opportunities in Vietnam were more structured and did not allow as much scope for participant observation as was possible in Cambodia. In Cambodia, surveillance was less direct but nonetheless present, especially at border crossings and in areas of high timber extraction. A key constraint in Cambodia was that I had less opportunity for informal discussions with border officials than I hoped for, as they approached me with a high degree of suspicion. I had to discern their roles and actions from the few interviews that I gained, as well as observations and accounts from other informants, such as cross-border traders and villagers. Overall, as the interview material presented in this book shows, I was able to broach quite sensitive matters during many of our interviews. I attribute this to the warmth and communication skills of my research assistants and the possibility that a middle-aged woman of South Asian heritage may have seemed quite innocuous to participants.

Although the acknowledgments cover my complete network of collaborators, it is important here to explain my research assistants contributions to the research process.