Any project of this scope is necessarily a collaborative effort. I would like to thank several individuals and institutions who have helped enable my research and writing.

To begin, two University of Mississippi College of Liberal Arts Summer Research Grants made it possible for me to research and illustrate this book. It simply would not have been possibleor nearly as visually interestingwithout the colleges generous support. We all thank you.

Special thanks go to Nanci Young of the Smith College Archives for helping me locate Composita after stumbling across a reference to a picture of a young lady who impressed him greatly written by Brahmin/banker/politician/photography aficionado W. I. Lincoln Adams in The Boston Daily Globe. Serendipitous discoveries such as these makes the work of research a true adventure.

Also, I would like to thank journalist Rob Rosenbaum, whose New York Times Magazine article on posture pictures brought the practice to a mass-culture audience for the first time. One of the biggest difficulties in telling a history for this now-virtually-extinct photographic practice has been finding surviving samples, and I thank Rosenbaum for sharing his thoughts with me about that challenge.

I would also like to thank the archivists at Amherst, Dartmouth, Harvard, Mount Holyoke, Radcliffe, Smith, and Wellesley Colleges for their help and hospitality. Likewise, thanks also go to the archivists at the Massachusetts Historical Society, Yale University, Ohio State Universitys Special Collections, and the Smithsonians National Anthropological Archives for their assistance.

On that note, several colleagues in my field have helped me hone my ideas as this project has evolved at conferences including the College Art Associations annual conference, SECAC, Nineteenth-Century Studies Association, Feminist Art History conference, and the Royal Anthropological Institute/British Museum/SOAS-University of London Art, Materiality and Representation interdisciplinary conference. I appreciate the feedback and the conversations I have had at and after those sessions with colleagues too numerous to mention here. But please know that I am most grateful for your time and for sharing your ideas with me. I hope my work has honored those conversations.

Thanks go to my editors, Margaret Michniewicz, Louise Baird-Smith, and Sophie Tann for their faith in my project and for their help making its publication a reality.

Eugenics is not an easy topic to live with and think about constantly. On a personal note, I thank University of Mississippi colleague Josh Brinlee for his good humor and support.

And finally, I thank Jane, John, Lily, and Avery for their patience, good humor, and for encouraging my work on this project from its genesis.

1

Harvards Class Portraits: Composite Pictures and a New England Aristogenic Agenda

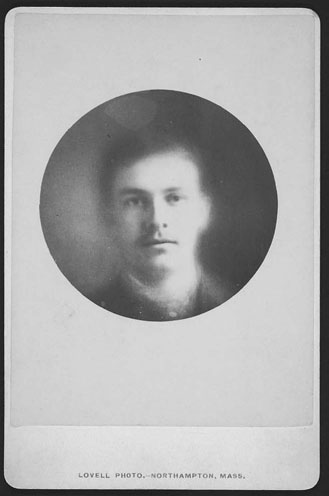

Lovell Photos Harvard composite class portrait of the colleges undergraduate Class of 1887 has a relatively pale face that is void of facial hair, and dark eyes that directly meet, but do not challenge, the viewers (

Class of 1887. Courtesy of the Harvard University Archives. Public Domain.

The subject exudes calm, quiet confidence as his featuresnone of which are too dominant or aggressiveare framed by conservatively cut dark hair and imbued with a haze that softens the young mans narrow hairline, ears, jaw, and neck.

Despite the descriptive specificity of the portrait subjects appearance, this composite photograph reveals the face of a young man who never existed. Instead, the image personifies the average outward appearance of the entire, all-male, graduating Class of 1887 at Harvard College. To make this portrait, Charles O. Lovell of Northampton, Massachusetts, carefully aligned and re-photographed dozens of portraits on a single negative to create a singular accumulated image from the multiple layers of exposures. Individual students facial features and bodies are obscured in a ghostly haze as they coalesce to form a data visualization, or aggregate image, of the whole group.

Copies of this composite photograph were sold as cabinet-card keepsakes to students and their families, and displayed/archived by Harvard College. But they also functioned as a representation of a particular social caste, Bostons Protestant Brahmin elite, for self-celebration, self-preservation, and the affirmation of community as immigration threatened its hold on power.

Holmes himself was a member of this distinguished Brahmin group. But apparently, so too were the soon-to-be-accomplished men of Harvard Colleges Class of 1887, a group of aspiring professionals in respected, Brahmin-appropriate fields: 42 percent practiced law, 23 percent were in occupations they defined as business, 16 percent went into education fields at various levels, 12 percent were physicians, and 7 percent became bankers.

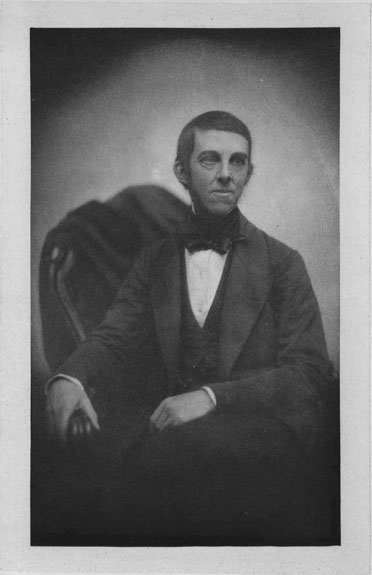

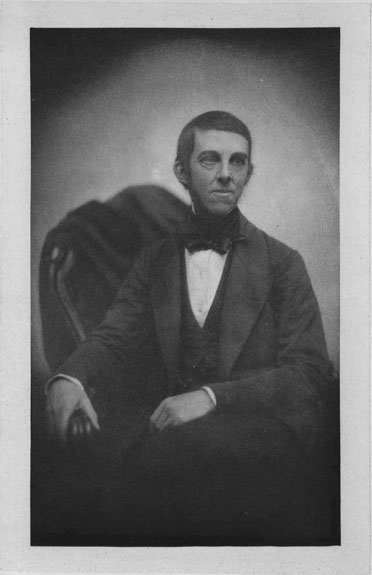

Holmess ).

Photographer unknown, Portrait of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., 1860. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, olvwork594981. Public Domain.

A clean-shaven, well-dressed, dignified, Holmes sits with his hands folded in his lap and meets the viewers gaze with a soft, non-confrontational expression. Holmess face is narrow, fair in complexion, and wears a calm expression. He is a self-composed and poised exemplar of the Brahmin ideal. Likewise, Lovells Harvard Class of 1887 composite is fair-skinned and also wears a calm, non-confrontational expression exemplary of Holmess definition of the Boston Brahmin. Such young men, after all, were likely to be heirs to roles in industry leadershippositions that required and rewarded sharp-thinkers who could remain stoic and rational in a crisis.

In a letter to eugenics movement founder/Englishman/friend Francis Galton, US eugenicist/physiology professor/Harvard Medical School dean Henry Pickering Bowditch marveled at how these composites showed a talented class of Americans who were singularly interesting and possessed beautiful faces!).

Other Thus, The Perfect Brahmin was self-deprecating, culturally well-versed, honorable, charming, social, highly educated, modest, and was born with a degree of privilege that opened doors to the potential for great accomplishments. Physically, he was not overly dominant or commanding, but instead exuded the dignity and refinement telling of his class.

As Holmess and Chapmans comments suggest, many quietly proud Boston Brahmins themselves felt their

Under Brahmin This is to say, a Harvard graduate was the most desired and most privileged type of individual in the country.

But the arrival of Irish immigrants challenged Brahmin political power and influence in the late nineteenth century. Dominating high culture served two purposes, Beisel suggests:

First, it allowed the elite to define and control an arena that was immune to the assaults of immigrants. High culture exemplified by magnificent public buildings allowed the upper class to define culture as something old, expensive, and European, available in American cities only because of upper class munificence and bestowed upon the public for its ennobling and civilizing effects. Second, high culture helped define class boundaries in an era when vast fortunes were being made and new upper classes were developing in cities around the country. Endowing scions with refined tastes increased the probability that they would choose an appropriate marriage partner, who either shared refinement from birth of who had acquired it because of elite schooling.