BATTLES

OF

ENGLISH HISTORY

BY

HEREFORD B. GEORGE

Published by Didactic Press

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Battles are the most generally interesting class of events in history, and not without reason. Until mankind have all been reduced to a single pattern, which would put an end to history, there will be conflicting interests, sentiments, creeds, principles, which will from time to time lead to war. We may settle many disputes peacefully by mutual concession, or by voluntary submission to external arbitration: but an appeal to arms always lies behind, and is the only resource when differences go too deep for reconciliation, or when the self-respect of nations is too severely wounded. Even within a nation there are many possibilities, remote perhaps yet never unimaginable, which may bring about civil war. And though it is perfectly conceivable that a given war may be waged to the end without a single important battle, if the superior skill of one side enables it to gain overwhelming advantage without fighting, yet practically this does not happen. Battles are in fact the decisive events in the contests which are of sufficient moment to grow into war. It is very easy to exaggerate their importance, to fix attention on the climax only, and lose sight of the events which led up to it, and which went very far in most cases towards determining its result. But after all the battle is the climax, and the world in general may be forgiven for over-estimating it.

Writers, whose humane instincts have been outraged by the way in which other people ignore the horrors of war, and dwell only on its glories, have sometimes argued that wars settle nothing, as they only leave behind a legacy of hatred which tends to fresh wars. No doubt in some cases, and in a certain sense, this is true. Napoleon trampled Prussia under foot at Jena, and the spirit engendered in the Prussian government and people by their ignominious defeat brought about in course of time the war of 1870, in which France in her turn was crushed almost as ruthlessly, to cherish ever since a hope of revenge. Still Jena was decisive for the time, and Sedan for a still longer period; and there is nothing to prove that France and Germany may not be the best of friends one day. If peaceful accord at one time does not prevent a future quarrel should circumstances alter, no more does past hostility prevent future alliance. Austria and Prussia were permanent, apparently natural, enemies during a century and a half, except when the common danger from Napoleon forced them into tardy and unwilling union; now their alliance is paraded as the permanent guarantee of the peace of Europe. Russia contributed more than any other power, except perhaps England, to the destruction of that fabric of universal empire with which Napoleon dazzled the French. Forty years later, another Napoleon joined England in making war on Russia and humbling her in the Crimea: now France and Russia advertise their enthusiastic attachment to each other. This is however only to say that men's interests will often be stronger motives of action than their passions; and if the interests of two nations conflict again in the present, as they have done in the past, their animosity will be all the keener for the memories of past defeats sustained at each other's hands.

Is it then undesirable that the memory of past wars should be fostered? Does it produce nothing but a longing for revenge on the part of those who have suffered defeat, a sentiment of vainglory on the part of the victors? Is the roll of English victories over France to breed in us nothing but an arrogant notion that an Englishman is worth three Frenchmen, an inference which the mere numbers engaged at Crecy or Agincourt, if we knew no more, might seem to justify? There is some danger that this may be the case, if we remember only the battles, the points of decisive collision, and take no heed to the wars as a whole, and to the contemporary conditions generally. An isolated battle is like a jewel out of its setting; it may look very brilliant, but no use can be made of it. The glories of Sluys and Crecy, of Trafalgar and Waterloo, would be a damnosa hereditas indeed, if they led us to despise our neighbours and possible enemies.

Battles however which are not isolated, but are fitted into their places in the wars to which they belong, and sufficiently linked together to make them illustrate the political and social changes from age to age which are reflected in the changes of armament, may be a subject of study both interesting and instructive. Detailed narratives of the battles themselves appeal to the imagination in more ways than one. There is the romantic element, not merely the "pomp and circumstance of glorious war," and the feats of brilliant courage which are often admired out of all proportion to their utility, but also the occasional startling surprises. What drama ever contained a more thrilling incident than the battle of Marengo, changed in a moment from a more than possible French defeat into a complete victory, through a sudden cavalry charge causing the panic rout of an Austrian column up to that moment advancing successfully? And there is the personal interest of noting how one man's great qualities, skill, promptitude, forethought, fertility of resource, in all ages, bodily powers also in the days before gunpowder, lift him above his fellows, and enable him visibly to sway their destinieshow the rashness and incompetence of another entail speedy and visible punishment. And behind and above all, is the great fact which of itself suffices to justify the universal interest, that the lives of the combatants are at stake. "All that a man hath will he give for his life;" yet the call of duty, or zeal for his cause, induces the soldier to expose his life to danger, never insignificant, and often most imminent and deadly; and discipline enables him to do this coolly, and therefore with the best prospects, not of escaping the sacrifice, but of making it effectual. The admiration of the soldier which is caricatured in the nursery-maid's love for a red coat is obviously silly, but the demagogue's denunciation of him as a bloodthirsty hireling is equally foolish, and far more mischievous.

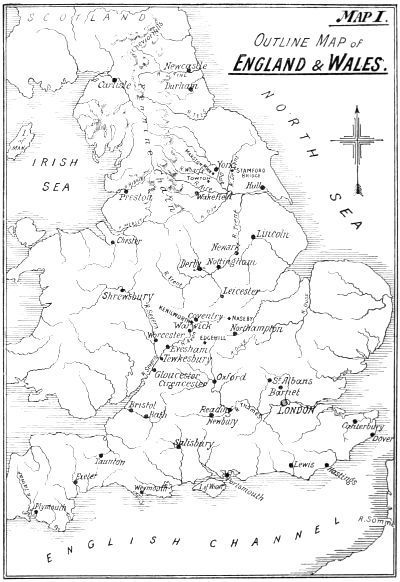

If detailed narratives are to be fitted into their historical place, the first question that suggests itself is why battles were fought where they were. The exact site is usually a matter of deliberate choice on the part of one combatant or the other, the assailant seizing his enemy at a disadvantage as he crosses a river, for instance, or the defendant selecting what seems to him the best position in which to await attack; and what position is most favourable obviously depends on the tactics of the age. Of the latter Hastings and Waterloo furnish conspicuous examples; of the former the clearest instance in English history is Tewkesbury. The locality however, as distinguished from the exact spot, is determined by a variety of considerations. Some are geographical: the formation of the country, which includes not only the direction and character of rivers and chains of hills, but also the position of towns and forests and the course of roads, limits in various ways the movements of armies. Some may be called political: the course of events practically compels the attempting of a particular enterprise. For instance, the battle of Bannockburn had to be fought because Stirling Castle was to be surrendered to the Scots, if an English army did not relieve it by a given day. The majority of the considerations involved are however strategical; and it is worth while to attempt to make clear what is implied by this often misapplied word.

![Mason Hereford - Turkey and the Wolf : Flavor Trippin in New Orleans [A Cookbook]](/uploads/posts/book/304852/thumbs/mason-hereford-turkey-and-the-wolf-flavor.jpg)