Contents

Guide

A wonderful, character-driven study.

Alexander Rose, New York Times bestselling author

Patriotism & Profit

Washington, Hamilton, Schuyler & the Rivalry for Americas Capital City

Susan Nagel

For Hadley

There is a tide in the affairs of men,

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

On such a full sea are we now afloat;

And we must take the current when it serves,

Or lose our ventures.

JULIUS CAESAR

A NOTE ON SPELLING

As scholar Jeremy Gregory has written, Eighteenth-century spelling was notoriously idiosyncratic, and nowhere more so than in the colonies, where diverging American spelling had yet to be cataloged and standardized. (Noah Webster, an incidental character in this narrative, performed much of that heroic work in his An American Dictionary of the English Language, 1828.) The spelling of American place names, especially those names transliterated from unwritten Native American languages, could be especially changeable; Potomac, for example, derives from an Algonquian word for a tribe settled along its banks, first recorded by Captain John Smith as Patawomeck in 1612. Its spelling remained unsettled for more than two centuries. When quoting from eighteenth-century letters, journals, diaries, and other contemporaneous accounts, I have preserved the writers original spelling, abbreviations, and punctuation. Thus, the reader will encounter Potowmack, Potomack, and Patowmac, among other adaptations.

PREFACE It Did Not Happen in the Room

ON MARCH 20, 1790. THOMAS Jefferson ferried across the Hudson River to New York City. It was the first day of spring, an auspicious day to join George Washingtons cabinet as secretary of state. After having lived luxuriously in Paris for five years while serving as Minister to France, Jefferson was affronted that his best housing option in lower Manhattan was unfashionable 57 Maiden Lane, which he was forced to lease from a grocer. Jeffersons seeming unpreparedness is surprising: he most assuredly knew beforehand that the city was teeming with politicians. The American Congress had been convening in New York City for over five years and operating there under the brand-new Constitution for more than a year. Jefferson also claimed that until his arrival he was supposedly unaware of any ugly bickering going on between the representatives of the northern and southern states. This, too, was disingenuous, as Jefferson had been in frequent correspondence with James Madison and others.

The young nation to which Jefferson had returned in 1790 was in danger of being torn asunder over two divisive issues: a permanent location for the new nations capital city and Alexander Hamiltons program for the federal assumption of wartime debts. We know many of Jeffersons thoughts about his life in New York City and his time of federal service there because he chronicled and published them. Jefferson asserted that he felt compelled to negotiate dtente, so he invited leaders of the two factions to a dinner party. Again, according to Jeffersons account, it was at this June 20, 1790, gathering where he, Jefferson, masterfully mediated the hard-won agreement that would reunify the country: the seat of government would remove to a swamp on the Potomac River to please the southerners in exchange for the necessary votes for Hamiltons plan, which would satisfy the north. Jefferson recounted this version of the dinner party three times: in his own papers in 1792, in a September 9, 1792, letter to George Washington, and in his memoirs published in a collection called the Anas.

Jeffersons narrative has been engraved in our nations lore as the Compromise of 1790 or the Dinner Table Bargain, and has been called one of the most pivotal and important moments in American history. Even Lin-Manuel Mirandas hip-hop dramatization, Hamilton: An American Musical, venerates the celebrated soire in the song, The Room Where It Happens. Sung by Aaron Burr, who would murder Hamilton in a duel, and who was excluded from Jeffersons dinner, Burr not only aches to be a player but also with great relish accuses Alexander Hamilton for posterity of sell[ing] New York down the river. That damning charge was Jeffersons intent. Miranda, however, gets it right in his refrain, Thomas claims.

Thomas Jefferson was merely a bit player in the drama now known as the Compromise of 1790. The protagonists engaged in the battle that would separate our financial capital from the political seat of power were close friends and rivals, President George Washington and New York Senator Philip Schuyler, whose parallel dreams, analogous visions, and similar skills provoked an intense, decades-long rivalry and protracted crusade for the location of the new empire city. Alexander Hamilton, son-in-law to Schuyler and surrogate son to George Washington, was helplessly caught in the middle. By the time of the now fabled dinner party at Jeffersons seedy quarters, Jefferson was openly seething with jealousy about the familial closeness between the president and his young protg, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton. Neither the funding bill nor the location of the permanent capital city of the American empire was settled at the summer solstice dinner party. The issues were protracted, as evinced in even Jeffersons own letters.

The true story that resulted in the dual passage of the so-called Assumption Bill and the Residence Act of July 1790 is indeed about selling down the riverit is, in fact, about two rivers, three men, only one of whomHamiltonwas at this legendary dinner party, and unchecked greed. Patriotism and Profit: Washington, Hamilton, Schuyler & the Rivalry for Americas Capital City is a timely companion to urgent current-day conversation and campaign rhetoric about draining the swamp. The story contains analogous themes that resonate today and will expose the roots of and reasons for some of our nations most pressing problems.

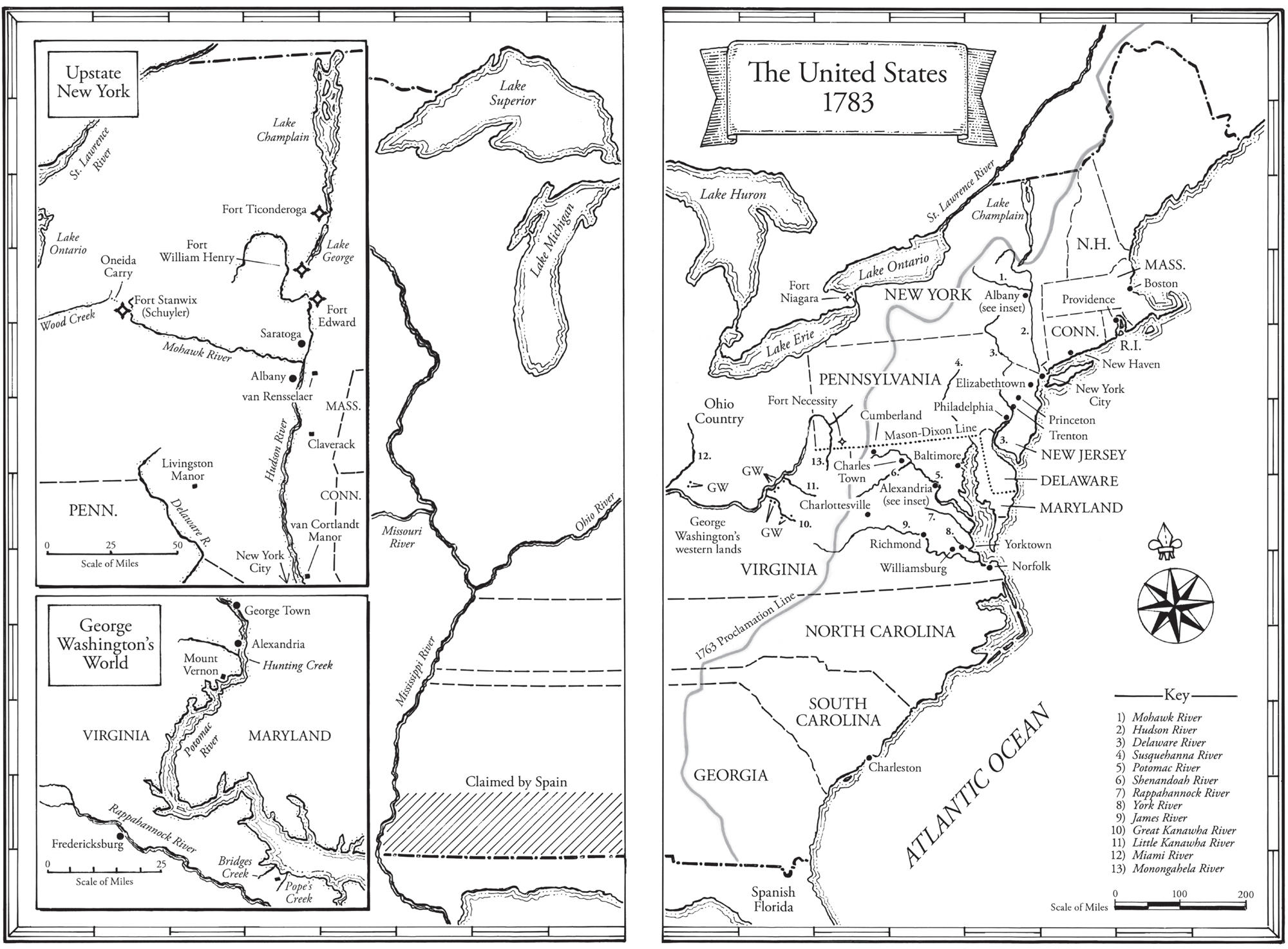

The financial and geopolitical wrangling among the European settlers on the North American continent had gone on long before the War of Independence. Before planes, trains, trucks, and cars, the only way to transport quantities of goods and people was via water. From the very moment when Captains John Smith and Henry Hudson sailed into Chesapeake Bay and into New York Harbor, respectively, in the early seventeenth century, a geomagnetic impulse to reach the Pacific Ocean via interior water routes pulsed in the blood of those daring to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

Some 175 year later, the Founding Fathers of the United States of America, acknowledging that they were birthing an empire, believed that it was essential for the seat of that empirethe new nations capital cityto connect the interior of North America with a coastal port along the Atlantic Ocean. In Philip Schuylers vision, New York City was the natural capital of the new empire. George Washington, however, was intent on depriving Schuyler of that trophy. Washingtons lifelong obsession was to establish the capital of the new republic in Alexandria, Virginia, some eight miles from his Mount Vernon plantation.