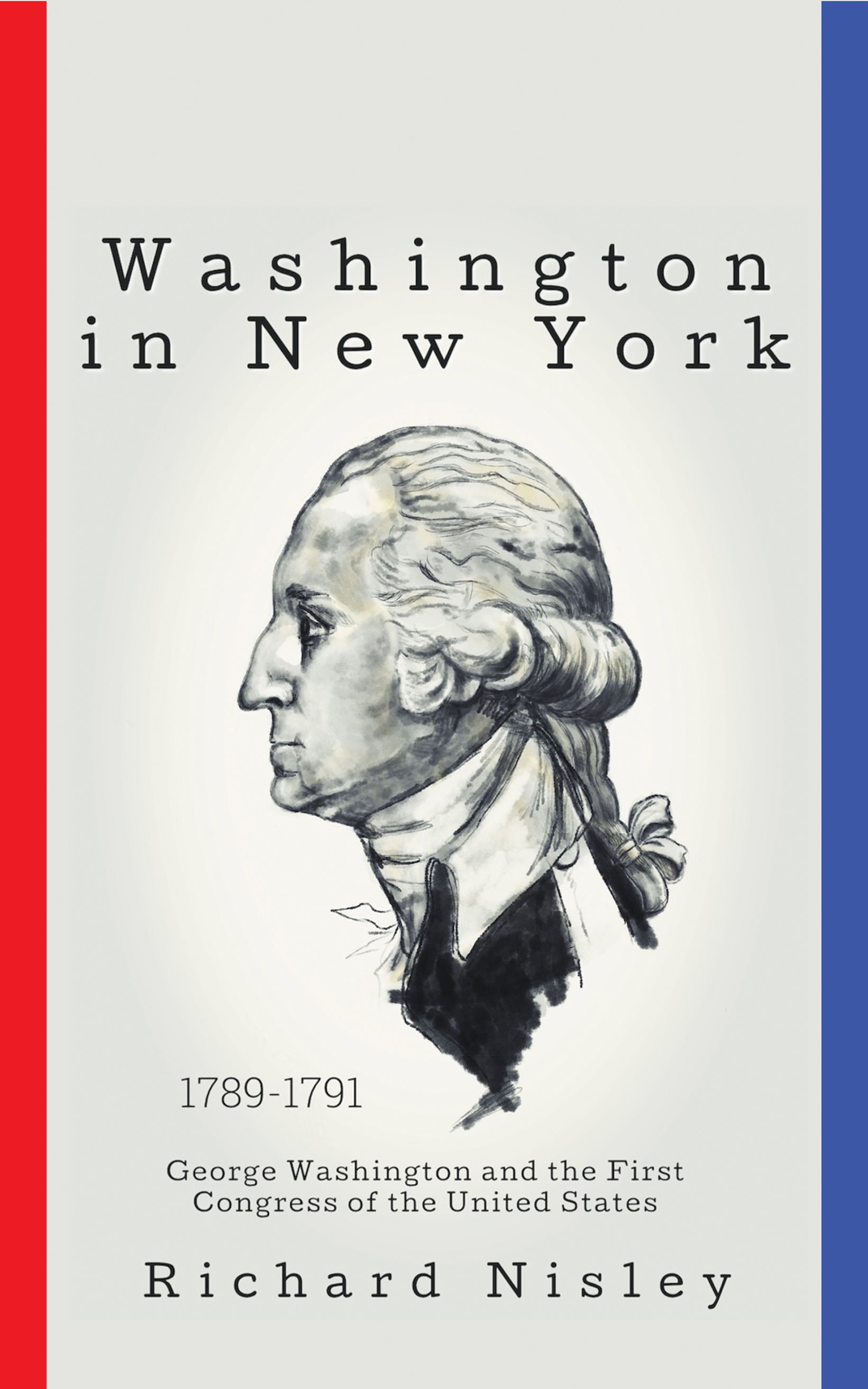

Washington in New York:

George Washington and the First Congress of the United States

Copyright 2019 by Richard Nisley

ISBN: 978-1-64398-916-7

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher or author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Although every precaution has been taken to verify the accuracy of the information contained herein, the author and publisher assume no responsibility for any errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for damages that may result from the use of information contained within.

Printed in the United States of America

LitFire LLC

1-800-511-9787

www.litfirepublishing.com

order@litfirepublishing.com

.

Washington in New York

George Washington and the First Congress of the United Stat es 1789-1791

by Ri chard Nisley

My object has been, and must continue to be, to avoid personalities.Georg e Washington

A new scene opens. The object now is to make our independence work. To do this we must secure our union on solid foundations. Its a job for Hercules for we must level mountains of prejudice. We fought side by side to make America free. Let us hand-in-hand struggle now to make her happy.Alexand er Hamilton

If men were angels, no government would be necessary.J ames Madison

With much love a nd affection

I dedicate this book to my two sons,

William David Nisley

and

Scott G erald Nisley

Special thanks to illustrator

Dea Lenihan for her ill ustrations,

particularly the cover illu stration of

George Washington.

For more, check out her website: www.dea lenihan.com .

Illustrations appear follow ing page 133

Contents

The King James Bible

on its 400 th anniversary

The Why? of American Exceptionalism:

Rutgers v. Waddington

Introduction

A Gateway to the West

George Washington must have had an exceptional imagination. How else to explain his decision to lead an army of green farm boys against an army of trained professionals, and expect to win? At Trenton, after a summer of devastating loses, Washington saw a way to turn the tables with a series of unexpected maneuvers and actually win a battleand did so. Coupled with a second victory a week later at Princeton, Washingtons ragtag army regained the upper hand. Five years later, at Yorktown, they delivered the coup de grce. If you can dream it, you can do it. Long before Walt Disney said it, George Washi ngton lived it.

After the war, Washington resigned as Commander-in-Chief and returned to Mount Vernon, only to discover he was broke. Yes, he had 200 slaves, but that didnt mean he was rich. As Adam Smith wrote about slavery in The Wealth of Nations: The experience of all ages and nations, I believe, demonstrates that the work done by slaves, though it appears to cost only their maintenance, is in the end the dearest of any. A person who can acquire no property, can have no other interest but to eat as much, and to labour as little a s possible.

Washington began looking beyond the Allegheny Mountains to the nations interior as a way out of his economic predicament. He owned property there which under the current state of affairs was worth next to nothing. If he could somehow link up the Potomac River with the Ohio River it would open up a vast new empire for economic growth. How? With a canal. Such a canal would make Virginia the nations economic center, and make his land holdingson both sides of the Allegheniesextreme ly valuable.

Washington had been dreaming of just such a waterway since boyhood. Before the Revolutionary War, he secured approval from the Virginia legislature for the formation of a stock company to improve navigation on the Potomac, and to charge tolls. With Maryland on the rivers north bank, approval from that state was necessary. However, opposition from Baltimore merchants who saw their city being bypassed in favor of Alexandria, Virginia, scuttled the deal. After the war, the ex-Commander-in-Chiefs prestige was such that the objections of a few nervous Baltimore businessmen was easily overcome, and the Potomac Canal Company was chartered by Maryland and Virginia. While investment capital was scarce after the war, Washingtons name attracted enough money to get the proj ect started.

Washington brushed up on his surveying skills and spent a good part of 1784 exploring the Allegheny Mountain range to determine the shortest and most practical route between the two rivers. The more he explored, the more he realized the enormity of the task. Above the fall line, the Potomac was a narrow, fast-moving mountain stream that would have to be opened up for 200 miles. The terrain rose so sharply that hundreds of locks would need to be built, dug out from mostly bedrock. Still, the more he looked the more he dreamed. He foresaw a centrally planned network of canals and improved rivers that would lead everywhere and bring navigation to almost every mans door. Best of all, it would make Alexandria the gateway to the West. Washington had an idyllic name for his dream water highwaythe Riv er of Swans.

The River of Swans called for untold amounts of investment capital and, as more states became involved, the need for a strong national government to regulate interstate commerce became paramount. At Mount Vernon in March 1785, Washington hosted a conference of investors and businessmen from Maryland and Virginia. Talk inevitably turned to the national governments inability to govern effectively. All real powerthe power to tax and spendresided with the states. Under the Articles of Confederation, the states were sovereign entities, 13 independent nation-states that since the Revolution looked after their own interests, bickered and bullied with one another and did absolutely nothing in the national interest. All the while the massive war debt went unaddressed; money was scarce, and the national economy was slipping into recession. If ever Washingtons canal was going to be a reality, it would require a strong national government to regulate interstate commerce and to have the wherewithal to restore the nations credit and thereby free-up investment capital. Before adjourning, Virginia proposed a convention of delegates from all 13 states to see how far a uniform system in their commercial regulations may be necessary to their common interest and their permane nt harmony.

The result was the Annapolis Convention, held in September 1786. Nothing happened because delegates from only five states actually attended. Before the convention adjourned, Alexander Hamilton proposed a convention in Philadelphia to address the heart of the matter: to render the constitution of the federal government adequate to the exigencies of the Union.

George Washington did not attend the Annapolis Conference nor did he plan to attend the Philadelphia Convention. He reminded friends that he was retired from public life. He was getting restless, however, and frustrated by states such as New York that were regulating commerce to their own advantage at the expense of smaller neighboring states such as New Jersey and Connecticut. It had to be stopped, if the young republic was to survive.