Pagebreaks of the print version

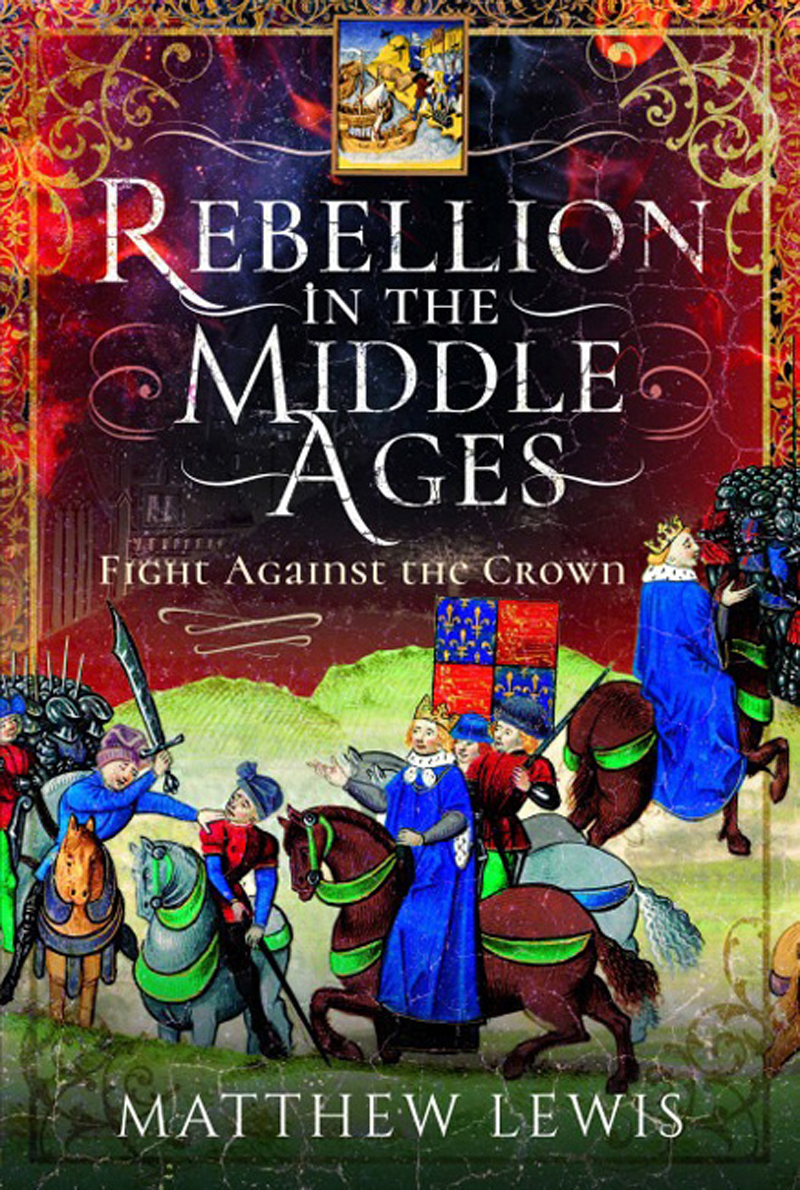

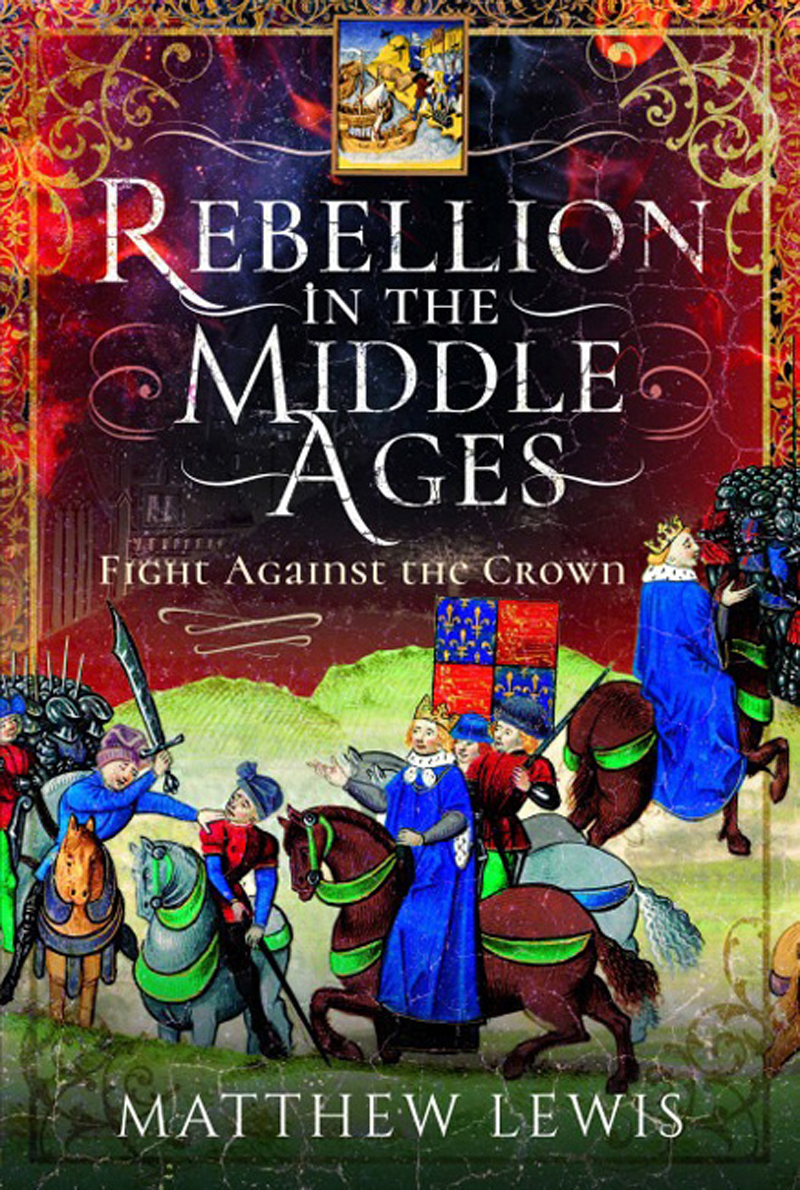

REBELLION

IN THE

MIDDLE

AGES

REBELLION

IN THE

MIDDLE

AGES

FIGHT AGAINST THE CROWN

MATTHEW LEWIS

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

PEN AND SWORD HISTORY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Matthew Lewis, 2021

ISBN 978 1 52672 793 0

eISBN 978 1 52672 794 7

The right of Matthew Lewis to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Introduction

There are few things more terrible than a failed rebellion. Nothing better guarantees the establishment in perpetuity of the perceived injustices that led to revolt than their successful defence.

Throughout the Middle Ages, from the Norman Conquest of 1066 until the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, rebellions in England came almost like clockwork. Around every fifty years between these convenient bookend dates the incumbent monarch would be forced to fend off a challenge of some kind. These rebellions must have been in each case an act of faith or utter desperation because the chances of success against a king and his massed force of arms, wealth, castles and knights were always lower than any rebel might like.

Each point of crisis for a monarch and his nation had very particular causes and aims. Sometimes it was a nobleman, an erstwhile friend of the king who had fallen from favour or been tempted to reach a little too far from his exalted position. On occasion, it was the more general populace who would be driven to seek the correction of a keenly felt injustice or the lifting of too heavy a burden placed across their collectively broad shoulders. Even the church might be a source of resistance to the royal will, particularly during the centuries that saw attempts to balance and rebalance the relationships between kings and popes.

We remain fascinated by the individuals thrust up before us as ringleaders or instigators of these moments of national, sometimes international, crisis. In some, we can see noble motives compelling them to act against the ultimate authority in the land. These hallowed few take on the aspect of the folk hero, the altruistic rebel obliged to react for the benefit of others despite the personal cost. They are the Robin Hood figures. These rebels fit perfectly with a view of the medieval world as intrinsically, fundamentally and inherently unfair. It surely was just that to the minds of later folk, who consider themselves more civilised and socially evolved. Quite what a thirteenth-century husbandman would make of the twenty-first-century obsession with twenty-four-hour availability to employers and strangers from around the globe, of screen time replacing conversation and of messaging the person sitting next to you in your living room rather than speaking to them is rarely given any consideration. It is our projection backwards of our own beliefs, bias and understanding, both of our world and theirs, that will often define these rebels as hero or villain.

I have always tried to shun a Hollywood notion of historical figures as either wholly good or entirely consumed by evil. Real life does not divide so neatly into goodies and baddies in an eternal struggle for supremacy. Nowhere has it been more challenging to resist the temptation to turn stories into would be movie scripts than in detailing rebellions against the crown. It lends itself to the portrayal of one side as just and the other as equally, irreconcilably unjust. I have tried to put down my bucket of popcorn and set aside my oversized bag of pick and mix sweets. Each crisis point had complex causes and every person who elected or felt compelled, or indeed was forced, to offer rebellion and resistance was driven by a mosaic of often conflicting motivations. These can be hard to pick out, piece together and, to the twenty-first-century mind, understand. For almost all, it must have been a difficult decision to reach that rebellion against the monarch was the right, or only, path available. It must have been so because the cost of failure was so high invariably mortal.

The willingness to pay this ultimate price, or at least to wittingly risk incurring it, only adds to the mystique that surrounds rebellions in a swirling fog of misdirection and romance. Most would have been aware that they ventured not only their status, where it was something valuable, and their lives, which to all were worth protecting, but the lives and livelihoods of those they loved. Entire families could be ruined, and where the rebel was a nobleman, he embarked on his undertaking fully aware that he might die, by execution if not in the act of revolt, but also that his family may well be dispossessed. His legacy, a vital part of the outlook of any baronial patriarch, would be the loss of the familys titles, lands and fortune. Why would someone take that gamble, with the odds so stacked against them, unless forced to it by some noble burden?

If a rebellion was given odds like a football match is today, few would back the rebel, though the potential pay-out might look alluring. If medieval politics was a casino, those entering did so at their own risk, as a large sign would warn them, and in the full knowledge that every game was rigged. The king was the house. The crown dealt the cards and set the rules, which might be changed at any moment. It could be this sense of injustice that causes one hopeful player to throw his chips in and turn over the table in outraged frustration. Still, in doing so, his aims are more likely to be restricted to anguish at his personal loss than a desire to help his fellow patrons and any future customers.

Religious resistance to the crown is easy to hold up as spiritual supremacy over a corrupt, grubby, secular world. The man at the casino who never gambles doesnt exist. Churchmen provided the lubrication for medieval government. At lower levels, they were the literate clerks who could keep records and draft documentation. They wrote the letters that conveyed the kings will and crammed into his household with no less ambition than those outside religious orders. Bishops and archbishops often acted as close advisors to kings and existed at the centre of the nations political life as much as its spiritual one. The seesaw that balanced secular and ecclesiastical duties was easily tilted toward the former, exposing them as every bit as worldly as the men they feigned to turn their noses up at around the court.