Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

DUTTON CALIBER and the D colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

has been applied for.

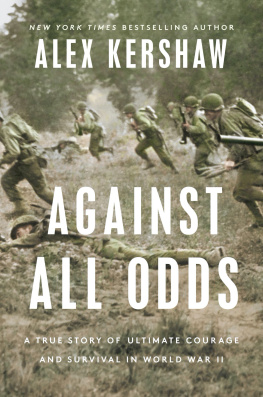

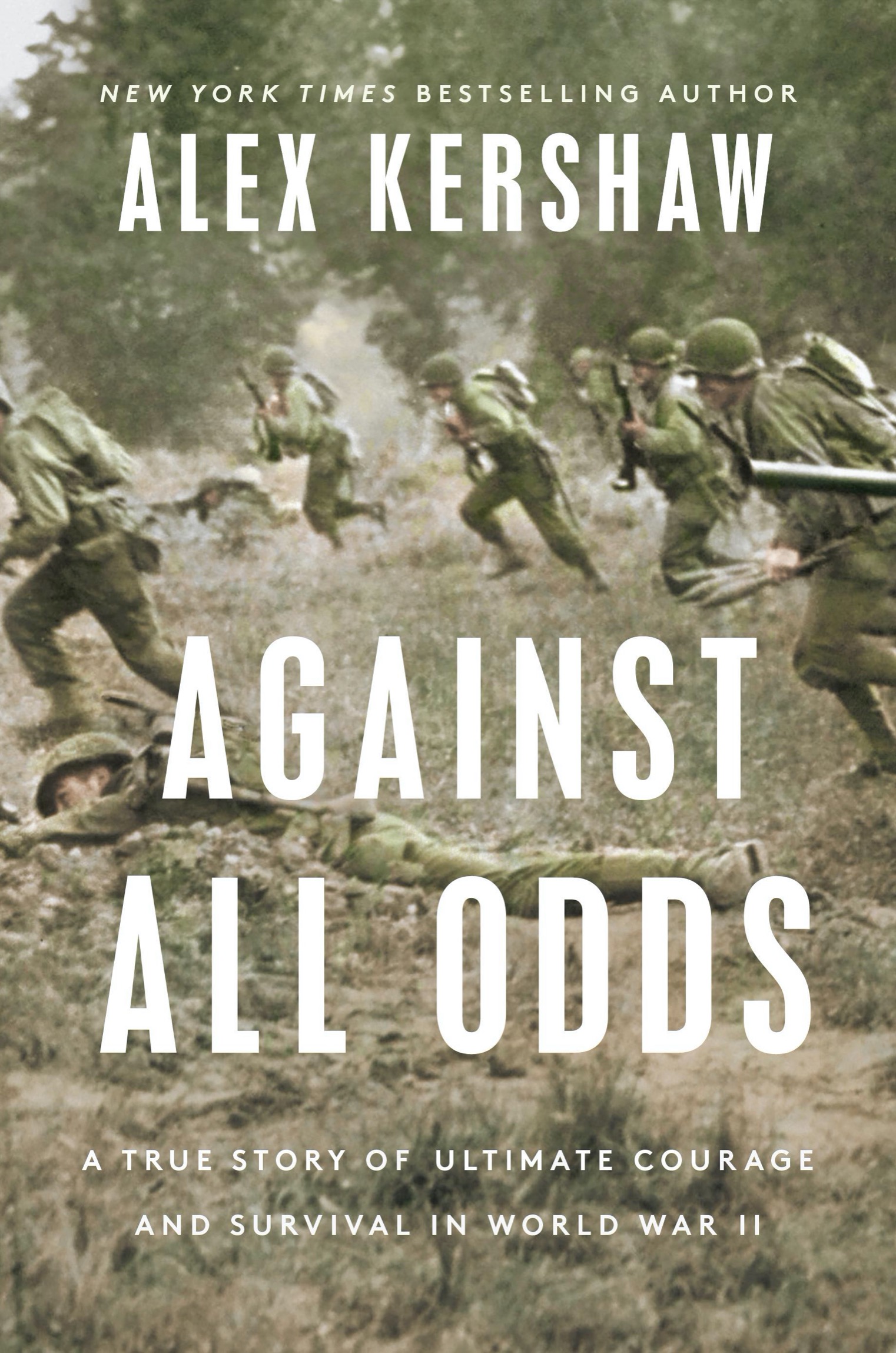

Cover design by Jason Booher; Cover image: 29th July 1944, US infantrymen dash across machine-gunned ground where they were facing SS troops. (Fred Ramage / Keystone / Getty Images)

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

CHAPTER 1

Baptism of Fire

The silence was unnerving after several days at sea, crossing from America with the constant grinding of the ships engines, quiet now in the Atlantic waters off North Africa. But it didnt last long. In the early hours, bells clanged and then soldiers heard an anchor chains rattle, barked orders, heavy and frantic footsteps, power winches whirring as they started to lower landing craft into the whitecapped water.

A radio played. Twenty-four-year-old Lieutenant Maurice Footsie Britt to his surprise heard the voice of President Franklin D. Roosevelt announce that the invasion of North Africa had already begun. We figured he had jumped the gun a little, Britt later remembered. After all, we were still eight miles from shore. Then blond-haired Britt, all two hundred twenty pounds of him, took his place in his landing craft. Finally, the craft headed toward the shore.

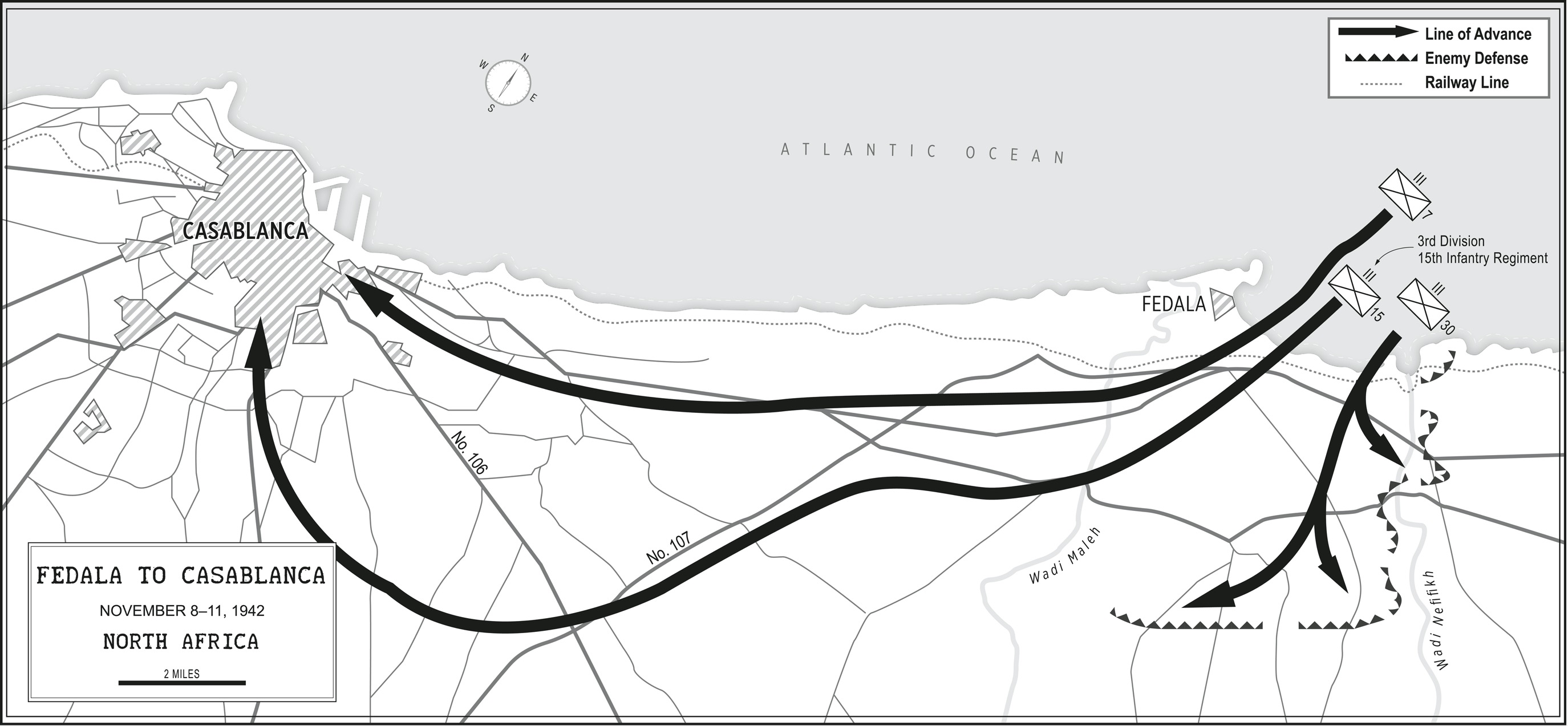

The seas as far as the horizon were dotted with transports. Britt belonged to the 3rd Divisions 30th Infantry Regiment, whose motto was Our country, not ourselves. He was one of thirty-five thousand green American troops in Western Task Force, commanded by General George S. Patton, one of three forces attacking French Morocco and Algeria in three areas of a thousand-mile-long coastline, stretching all the way from Safi on the Atlantic to Algiers. The arrival of the first Americans in Europe to fight the Axis powers came at a critical point in the war. After enjoying stunning success against the British 8th Army through 1941 and much of 1942, General Erwin Rommel and his famed Afrika Korps were now on the defensive, having been defeated at El Alamein in Egypt less than a week earlier.

In all, the Torch Landings, the first joint operation of the war by the Americans and the British, comprised more than a hundred thousand troops backed by three hundred fifty warships from seven Allied navies. The Americans had tried to negotiate an armistice with the French in recent days but to no avail, and so an order had come from on high to Britts division: Okay, boys, lets play ball.

Dawn was now breaking off the coast of North Africa. In the far distance, men could make out the steeple of a Catholic church rising above the port of Fedala. There was the sound of machine-gun fire. Bright red tracers spat across the lightening sky. Ahead loomed a flat, broad beach a couple of miles to the east of Fedala.

Britt heard the drone of French bombers and then saw huge fountains of spray as bombs crashed into the sea. It was a pretty sight, he remembered, until suddenly we realized, with a sickening feeling, that the men in these bombers were trying to kill us. No lectures on the subject, no crawling under carefully aimed machine gunfire, will ever make a soldier. He becomes one the instant he realizes the gunfire he hears is intended to kill him.

Britts landing craft ground ashore. Men began to unload it but then there was a deafening rattle of fire and Britt looked up and saw a French plane diving toward him, strafing his regiment. There had been no preinvasion bombardment in the hopes that the French would not put up any resistance. Many of Britts fellow invaders carried American flags, figuring the French would be less likely to fire on US troops. The flags made no difference.

Britt and his men stopped unloading the craft, headed for safety across the beach, and then moved inland. By midday they had reached a preassigned assembly area near a road bridge. Then Britt returned to the beach with a sergeant to salvage the jeeps and equipment hed been forced to leave in the landing craft. The first edge of my excitement was beginning to dull and when another strafing plane came over I hit the beach in utter terror, digging madly into the sand.

The plane soon passed over, in search of more targets. For five long minutes, Britt lay flat, terrified, trying to summon the courage to get back on his feet. He then found his landing craft. But before he and the sergeant could pull off several guns and two remaining jeeps, the landing craft sank in the rough seas. There was more bad news. Britt learned that a submarine torpedo [had] hit our transport standing off shore and all our equipment went down with it. We lost all our barracks bags, food, kitchens, and other equipment. All we had left was the clothes on our backs and the rations we carried. We were tired, sick, and disgusted.

Britt and the sergeant had no option but to walk back across the beach and rejoin their company at the assembly point by the road bridge. By early afternoon, Fedala was in American hands, and Britt and his company were marching toward Casablanca, sixteen miles to the southwest. Britts regiment encountered minimal resistance while taking dozens of French soldiers as prisoners.

Allied Supreme Commander Dwight Eisenhower arranged a cease-fire with Vichy French forces forty-eight hours later, on November 10, and Casablanca was occupied with fewer than seventy men killed from Britts division, although by the time the guns fell silent in all of Morocco, there had been some fifteen hundred Allied casualties. Britt and his fellow Marne men, as the 3rd Division soldiers were known, had been initiated into the full chaos and confusion of combat in a couple of hectic, feverish days. Theyd fought with barely any armored support yet had successfully spearheaded the first US invasion of the war. My biggest thrill, Britt wrote his wife, and one that Im sure Ill never recapture, was when my boys performed so heroically that at least three will be decorated for outstanding bravery.