Bretwalda Battles

The British Raj

The Battle of Kabul 1879

by

Oliver Hayes

This series of book has its own FACEBOOK PAGE where you can join the conversation.

*****************

Published by Bretwalda Books

Website : Facebook : Twitter

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

First Published 2012

Copyright Bretwalda Books 2012

ISBN 978-1-909099-12-8

*****************

Contents

*****************

The Second Afghan War

It was Russia that caused the war between Afghanistan and British India, of which the Battle of Kabul was a part. Throughout the 19th century the Tsarist Russian Empire had been expanding into Moslem Central Asia. Some Emirates had been conquered, others forced to cede territory or trading rights. In 1878 Tsar Nicholas II decided that Afghanistan was to be next.

The first Russian move was to send an envoy to Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, to open talks with Sher Ali Khan, Emir of Afghanistan. Ali Kahn, knowing only too well what the Russian move meant, refused the Russians permission to enter his domains. The Russians came anyway. The British, who ruled India to Afghanistan's southeast, countered by insisting that Ali Khan accept a British envoy as well, and sent an army to enforce the demand.

Yaqub Khan, the Emir of Afghanistan during the Second Afghan War.

Sher Ali Khan died in February 1879 and was replaced by his son Mohammad Yaqub Khan. Yaqub Khan hurriedly made peace with the British, ousting the Russian envoy and agreeing to have an official British diplomat in Kabul. He also handed over the strategic Khyber Pass to British control. The agreement was signed in May 1878 and in July the new British Resident in Kabul, Pierre Cavagnari, set out for the mountain kingdom. He took with him an assistant, a doctor and a company of the Corps of Guides. The mission rode off over the mountains into Afghanistan, and the British forces in India settled back to peacetime routine.

Pierre Cavagnari led the British mission to Kabul, and proved to be a disastrous and fatal choice of diplomat.

Just after dusk on 3 September an exhausted and dirty trooper of the Guides rode into a British outpost on the Shuturgurdah Heights on the Afghan-India border. He blurted out that a force of Afghan soldiers had attacked the British Mission. The trooper had been off the site at the time of the attack and had ridden for help, he was not certain what had happened after he left. At about dawn a second trooper came in. He had likewise not been with Cavagnari when the attack had begun, but he had remained in Kabul to await developments. Once it had become clear that Cavagnari and everyone with him in the British Mission had been killed, the Guide had stolen a horse and fled.

A rider was despatched from Shuturgurdah to the nearest telegraph station with the news. The Viceroy of India, Lord Lytton, received the news of the massacre at his summer capital of Simla on 5 September. Lytton at once sent for the most talented soldier in British India, Frederick Roberts, and sent him at top speed to take command of a division in the Kurum Valley, close to the Afghan border. Roberts's orders were simple - to go to Kabul, find out what had happened and punish those responsible.

When Roberts arrived he found his force consisted of 7,500 men. The cavalry was commanded by Brigadier Dunham Massy, the infantry brigades by Brigadiers MacPherson and Baker. There were men from several units, including the 9th Lancers, the 72nd and 92nd Highlanders, the Hampshire Regiment, the Guides, the 14th Bengal Lancers, the 5th, 23rd and 28th Bengal Infantry, the 5th and 12th Punjab Cavalry and the 2nd, 4th and 5th Gurkhas. There were also three batteries of light mountain artillery.

After a couple of weeks spent gathering supplies and seeking information from travellers coming out of Afghanistan, Roberts set off up the Kurum Valley and over the passes into Afghanistan. As he advanced he met envoys from Emir Yaqub Khan. These men brought messages of friendship and support, they said that the attack on the British Mission had been carried out by troops rebelling against Yaqub Khan and that the Emir wanted nothing more than peace with Britain. Roberts replied he would see when he got to Kabul.

*****************

The Campaign in Afghanistan

On 6 October Roberts found his route blocked at the entrance to the Sung-i-Nagusta Gorge near Charasiah. An old fort in the mouth of the gorge was held by Afghan troops, as were the hills above while a battery of cannon swept the approaches to the gorge. Roberts sent forward half his infantry under the cover of an artillery barrage which utterly destroyed the fort and knocked out most of the Afghan guns. The entrance to the gorge was forced by the infantry who fired systematic volleys of rifle fire before advancing with fixed bayonets.

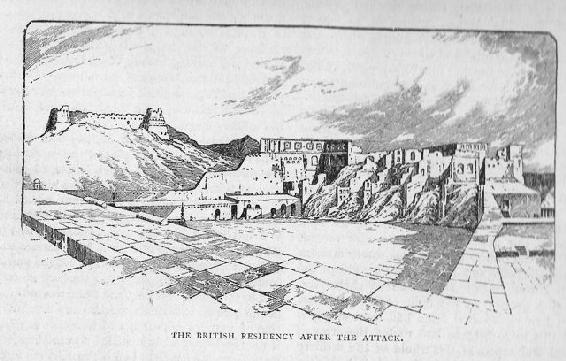

Three days later, Roberts reached Kabul. The Sherpur Cantonment, the main military base outside the city, had been abandoned by the Afghans, so Roberts moved his force in. He then went up into the old fortified royal palace, the Balla Hissar, to view the ruins of what had been Cavagnari's residence. The bodies of the dead were recovered and given decent burials according to their faith.

The ruins of Cavagnari's residence as sketched by a member of Roberts's force in 1879.

Roberts then summoned a durbar to be held in the audience chamber of Yaqub Khan's palace. Tribal leaders, army officers and nobles from across Afghanistan were summoned, and most came. One man prominent by his absence was the Governor the city of Herat, Ayub Khan, brother to Yaqub Khan.

The arrivals were met by Roberts who seemed in a genial mood. He promised friendship to the peoples of Afghanistan, said that British India wanted only peace and treated Yaqub Khan politely. However, nobody present could miss the fact that they had all been searched for weapons on arrival and that the walls of the audience chamber were lined with British soldiers carrying loaded rifles with fixed bayonets. Clearly Roberts was taking no chances.

Next day Roberts announced that Yaqub Khan was deposed from his position as Emir of Afghanistan and would be sent to live in exile in India. Although Roberts had established that the British Mission had, indeed, been killed by troops in a state of mutiny, his orders from Lytton had insisted that the Emir had to go. Yaqub Khan was led away and escorted over the hills to India where he was given a nice house and generous pension. Some time later a British official remarked to the exiled prince that he must be sad to live in exile. "Oh no," replied Yaqub Khan. "I would rather work as your servant, cut grass and tend your garden than be the ruler of Afghanistan."