Bretwalda Battles

The Wars of the English Kingdoms

The Battle of Wimbledon (568)

by

Oliver Hayes

*****************

Published by Bretwalda Books

Website : Facebook : Twitter

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

First Published 2012

Copyright Bretwalda Books 2012

Oliver Hayes asserts his moral rights to be regarded as the author of this work.

ISBN 978-1-909099-23-4

*****************

Contents

*****************

The Outbreak of War

The Battle of Wimbledon is something of a mystery. We cannot be certain of either the precise site nor the exact date of the battle. But we do know that it was a landmark battle fought between the two most powerful rulers in Britain for control of the island. The winner of the savage struggle fought here would rule Britain for the next 20 years. If much about the battle is obscure, the importance of the result is startlingly clear. Put simply this was one of the most decisive battles fought in 6th century Britain.

The 200 years or so of British history after the Roman Empire abandoned the province of Britain to its own devices in 410 have long been known as the Dark Ages - and with good reason. Almost no contemporary written documents have survived from those times. The historian is reliant on documents written much later or hundreds of miles away. While archaeology can add something to the broad outline of trends, it has little to say about precise events.

Any account of these years must be filled with words such as 'perhaps', 'maybe' and 'probably'. This account of the great battle fought at Wimbledon is no exception, but the broad thrust of events that brought thousands of men to battle to decide the fate of Britain are clear.

A gold coin of the Emperor Honorius. On one side is a portrait of the emperor while on the other he is optimistically shown defeating a barbarian and being crowned with a laurel wreath of victory by an angel. It was Honorius who abandoned Britain and thus inadvertently set the stage for the Battle of Wimbledon.

When the Roman Emperor Honorius abandoned Britain in 410 he told the locals to look after themselves until Rome had sorted out the barbarians, after which the Romans would be back to run Britain again. Of course that never happened. Rome itself fell to the Goths later in 410, then in 476 the last Emperor was deposed.

In Britain the Romano-Britons tried to keep their state and civilisation going, with very mixed results. Roman Britain had been ruled by a governor appointed by the Emperor and defended by an army and navy commanded by men similarly appointed from Rome. Local government was in the hands of a dozen or so local councils, the civitates, elected by the richer men in the area. At first the councils themselves elected a governor and military commanders. But as it became clear that Rome would never return to run Britain the local civitates began to grow increasingly independent of the governor. Instead of paying taxers to the central British government, the civitates kept it for themselves. They raised their own armies and ordered their own affairs.

At the same time there was a dramatic collapse in the economy and culture of Britain. Trade with the rest of the Roman Empire had brought wealth and prosperity to Britain, but with the Roman Empire imploding that trade died off. Poverty and often starvation stalked the land. The big Roman villas and many towns were abandoned as Britain slid from being a wealthy society based on trade and industry to one of subsidence agriculture. Then a terrible plague struck in the 540s and about one third of the population was wiped out in a single year. This was not a good time to live in Britain.

A disrupting influence to this gradual disintegration of Britain-wide government came from across the North Sea. Both the central government and many of the eastern civitates hired groups of Germanic mercenaries to guard their borders, or to force increasingly reluctant and impoverished farmers to pay their taxes. Many warriors brought their families with them to settle in Britain.

A Germanic mercenary in Roman pay about the year 440. He has German style spear and shield, but his clothing and chain mail shirt are of Roman manufacture.

The chronology and course of events is difficult to follow, but while the Romano-Britons sought to retain their culture, power and Christian religion in Britain under rulers such as Vortigern, Ambrosius and Arthur, the incoming Saxons and Angles eyed the wealth of Britain with covetous eyes. Some of the nascent English took their pay as mercenaries, but others were after bigger prizes. At some date, perhaps as early as the 480s, the English got control of the civitas of Cantium, renaming it Kent. The civitas of the Regni was also taken over by English rulers, the new state later being named Sussex.

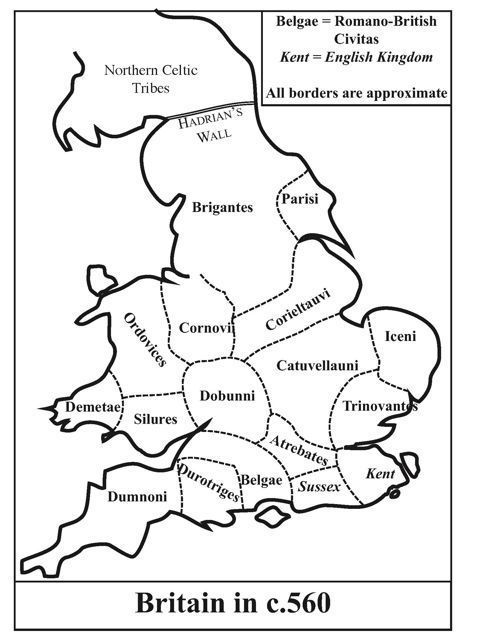

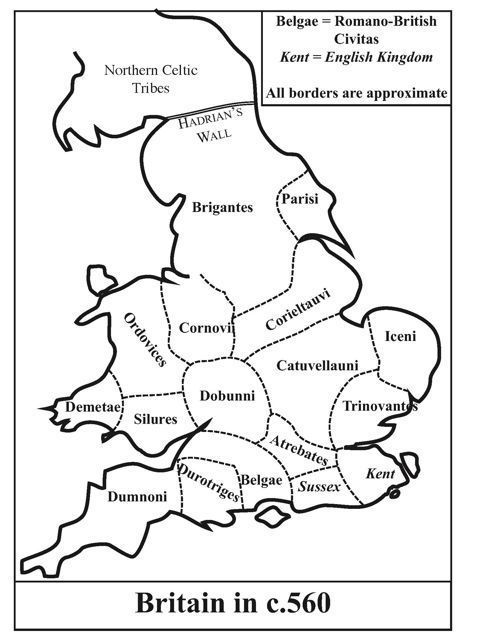

Post-Roman Britain at first had a central authority under a governor, with local government affairs dealt with by the civitates. Over time the civitates became increasingly independent, while English invaders established their own kingdoms. The dates at which these changes happened is poorly understood, but by about 560 most of Britain seems to have remained in British hands, with the English controlling only Kent and Sussex.

By the 560s the majority of Britain remained in the hands of Romano-British rulers. Their society was falling to pieces about them, but they remained in political control. How many civitates retained a Roman-style limited democracy and how many had fallen into the hands of military hard men we do not know. Too many records were lost in the years of chaos that followed for us to be certain. We can be fairly certain, however, that the cogitates were by this date largely self-governing but did still recognize the vague and indeterminate over lordship of the man who occupied the office descended from that of the Roman governor.

It seems that until he died in the great plague of 547 that office had been held by Maelgwn, ruler of Gwynedd in what is now north Wales. After his death his son Rhun Hir (the Tall) took over Gwynedd and tried to enforce his claim to the overlordship of Britain south of Hadrian's Wall. He was successful only north of the midlands, southern Britain was up for grabs and two monarchs made the try.

The first of these was Ceawlin. Later generations would remember Ceawlin as an early ruler of the Kingdom of Wessex, but he himself would have seen himself as a Prince of the Belgae. This civitas covered what is now Hampshire and Wiltshire and at some point had taken over the civitas of the Durotriges, modern Dorset. The Belgae had recently lost a war, and with it much of what is now Somerset, to the civitas of the Dobunni (which covered what is now Gloucestershire, Worcestershire and much of the Severn Valley. The failure of Rhun Hir to take over as overlord of Britain will have been seen by Ceawlin as an opportunity.