Bretwalda Battles

The Peninsular War

The Battle of Talavera (1809)

by

Oliver Hayes

*****************

Published by Bretwalda Books

Website : Facebook : Twitter

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

First Published 2012

Copyright Bretwalda Books 2012

Oliver Hayes asserts his moral rights to be regarded as the author of this work.

ISBN 978-1-909099-29-6

*****************

Contents

- The Peninsular War

- The Commanders at Talavera

- Weapons, Soldiers and Tactics

- The French Army

- The Spanish Army

- The British Army

- The Portuguese Army

- The Battle of Talavera

- After Talavera

************

The Peninsular War

Talavera was a battle fought near the start of the Peninsular War, the struggle that wracked the Iberian Peninsula from 1808 to 1814. That war was but one part of the wider Napoleonic Wars that engulfed Europe in a series of wars and campaigns that lasted almost 20 years and stretched from the Atlantic to Moscow and reached overseas to India, the Caribbean and the Near East. But although the Peninsular War was a part of the wider conflict, it had some unique characteristics that made it a peculiarly savage and hard-fought conflict.

In the earlier stages of the Napoleonic Wars, Spain had remained neutral or actively taken the side of France against the various coalitions that sought to crush Napoleon, the self-proclaimed Emperor of the French. Spain saw the opportunity to make gains for herself, while the French had no ambitions south of the Pyrenees. The situation began to change in 1807. Napoleon stood triumphant in Europe having defeated Prussia, Austria and Russia on the battlefield and having cowed the smaller states into submission. His only remaining enemy was Britain, and there he had a problem.

In 1805 Britain's Admiral Nelson had crushed the combined fleets of France and Spain at the Battle of Trafalgar. As a result, Napoleon had no chance of invading Britain with his magnificent army. Instead he sought to bring Britain to peace talks by crippling her trade. By blocking every European port to British merchant ships, Napoleon believed, he would do so much damage to British wealth that peace on his terms would be inevitable. Not all the European countries wanted to join such a blockade, but one by one they succumbed to Napoleon's threats and bluster. By October 1807 only Portugal still refused to join this Continental System, as it was known.

In November, Napoleon agreed a treaty with the Spanish Prime Minister, Manuel de Godoy. In return for French troops being allowed to march through Spain to invade Portugal, the Spanish would get the Portuguese fleet and various overseas colonies, and as an added inducement Portugal would be divided into three minor states under Spanish domination. The Portuguese did not wait about to be destroyed. Queen Maria I fled from Lisbon on 29 November along with her family, the Portuguese fleet, most of the merchant ships and thousands of soldiers. She moved to the Portuguese colony of Brazil where she set up court along with her son and regent John. John, later King John VI, appealed to Britain for help. John left orders in Portugal that there should be no resistance to the French in order to avoid bloodshed. The royal flight was, he said, only temporary and soon all would be right.

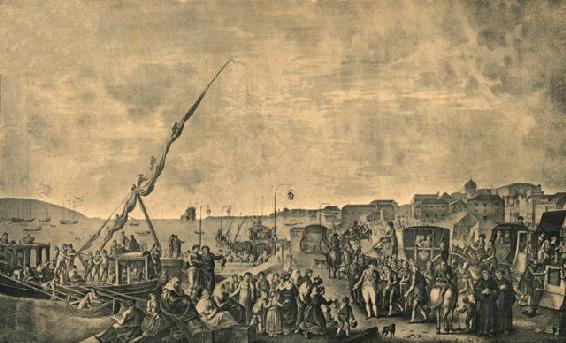

The embarkation of the Portuguese Royal Family at Lisbon. Queen Maria and the Regent John fled in the face of overwhelming French force and headed to Brazil from where they appealed to Britain for help.

Napoleon, meanwhile, had become more ambitious. Rather than merely close the Iberian ports to British trade, he now wanted to gain complete control of the Peninsula by merging Portugal into Spain and making his own brother, Joseph, King of Spain. His moves were made slowly. First larger numbers of French soldiers marched into Spain, claiming to be on their way to Portugal to occupy that country. In February Napoleon ordered his men in Spain to seize key Spanish fortresses and military bases using the pretext that they were needed to safeguard the supply lines to the French troops in Portugal.

King Charles IV of Spain began to grow alarmed as the numbers of French troops in Spain passed the 100,000 mark. At the same time Spain was suffering an economic crisis, caused largely by the loss of trade to the American colonies that had followed the Battle of Trafalgar. The populace and many nobles blamed Godoy for the pro-French policy that was causing such poverty and hardship. On 17 March 1808 Charles and Godoy stopped for the night at the town of Aranjuez on their way to Andalusia from Madrid. That night a mob stormed the house where Godoy was staying, dragged him from his bed and held him prisoner. A group of nobles at court persuaded Charles that the only way to save Godoy was for him to abdicate in favour of his son, Ferdinand. Many nobles opposed the move and urged Charles to take back the throne.

King Ferdinand VII of Spain came to the throne amidst civil turmoil and government bankruptcy. He subsequently played straight into Napoleon's hands and was forced to abdicate as King of Spain.

Napoleon appeared on the scene playing the role of honest broker. He suggested that both Charles and Ferdinand should come to Bayonne in southern France so that they could all discuss the situation in Spain and come to an amicable solution. The two rival kings arrived in April but soon found they were prisoners. On 5 May Napoleon forced both Charles and Ferdinand to abdicate in favour of himself. He then handed the crown to his brother, Joseph, who was reluctant to accept the honour as he had been enjoying himself living in Naples. Nevertheless Joseph bowed to his brother's wishes and set off for Madrid.

Before Joseph could get to his new kingdom, however, the war had begun. On 2 May, the local French commander, Joachim Murat, ordered the daughter and younger son of King Charles to be put in a carriage and sent to Bayonne. The pair refused to go, so Murat sent a battalion of infantry to the royal palace to enforce his instructions. As news of events spread a huge crowd of Madrid citizens began converging on the palace. In circumstances that remain unclear the French soldiers opened fire on the crowd. The Spanish rose in revolt, using whatever knives, axes or guns came to hand. Some units of the Spanish Army in Madrid joined the fighting that raged through the streets of Madrid like wildfire.

Murat sent in reinforcements, including the feared Mameluke cavalry, and by nightfall had restored order. Around 150 Frenchmen and several hundred Spaniards were dead. Next day, Murat and General Grouchy set up a military court that sentenced more than 500 Spaniards to death, all of them shot by firing squads before dusk fell on 3rd May.