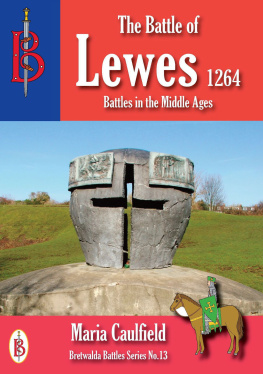

Bretwalda Battles

The Baronial Wars

The Battle of Lewes 1264

by Maria Caulfield

Published by Bretwalda Books

Website : Facebook : Twitter : Blog

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

First Published 2014

Copyright Maria Caulfield

Maria Caulfield asserts her moral rights to be regarded as the author of this work.

ISB N 978-1-910440-22-3

Contents

The impact and significance of the Battle of Lewes, whilst celebrated and remembered locally, often goes underplayed by national historians. Unusually at the time the battle was not about gaining land or wealth but was fought on the principle of getting better, fairer government and resulted in Britains first ever representative parliament. My interest in writing this book came initially from a political stance rather than a military one because as a local nurse who is standing for Parliament, I owe a great deal to the outcome of this battle.

In the year of the 750th anniversary of the Battle of Lewes, this book reminds us of how hard generations before us have fought for our democracy and freedom and if things had turned out differently, how easily democracy may have escaped us. At a time when many people are disillusioned with politics and politicians, the Battle of Lewes illustrates how precious our freedom to choose those who represent us in Parliament really is. Britain as a nation and in fact most of the Western World owes a great debt to those who fought on the battlefields of Lewes that day.

My aim in writing this book is to highlight the motives behind the battle and identify the key people and stages involved. What fascinates me about this battle in particular is how at each and every stage the battle could have been so easily won or lost. Personalities seemed to play a huge part in the battle itself and really influenced the final outcome rather than military tactics. The book also underlines how short lived the success of those involved was with Simon De Montford being killed in battle within the year.

Ultimately the book is a short guide to the battle because while the people of Lewes are very familiar with the tale, outside of the town the story about the day which changed the history of this country remains largely unknown.

A huge thanks go to Rupert Matthews and all at Bretwalda for their help and support and to the people of Lewes for keeping the story alive.

Maria Caulfield

The Barons War

The dispute that led to bloodshed at Lewes on a beautiful spring day in 1264 originated with King Henry IIIs determined insistence that he had the sole right to rule England as he wished, combined with his utter inability to do so competently - or indeed at all. If he had been less autocratic or more competent his reign may have passed by peaceably, but as it was civil war wracked the kingdom. But out of that bloodbath was born the foundations of the democracy that England, Britain and many parts of the world have gone on to enjoy.

King Henry III, who ruled England from 1216 to 1272.

Time after time Henry raised taxes for one purpose, then spent the money on something else. He went to war without consulting his nobles, but then expected them to muster the men he needed. He lavished money on the Church, and saw no reason to object when that money was spirited out of England to fund lavish lifestyles for prelates in Rome. An early sign that the nobles were not going to take all this lying down came in 1243 when Papal Legate Martin travelled to Shropshire to find out why taxes levied by the Pope had not been paid.

A local magnate named Fulk FitzWarin listened to the legate, then replied

I tell you to go, leave this land at once.

What is your authority to give orders to the legate of the Holy Father? demanded the outraged Martin. For reply FitzWarin drew his sword and laid its point at Martins throat. Martin left without his money.

Such incidents were at first few, scattered and local, but in 1258 events moved to the national stage. Henry had lost an unnecessary war with France, then launched an invasion of Wales that was called off before the army even crossed the border. Both military adventures had been expensive, but even more so was Henrys ambition to make his brother Richard, Earl of Cornwall, the Holy Roman Emperor and his younger son Edmund the King of Sicily.

At this date a new Emperor was elected when the old one died. The electorate was restricted to the seven most powerful noblemen in the Holy Roman Empire: the Princes of Cologne, Mainz, the Palatinate, Bohemia, Saxony, Brandenburg and Trier. Previously there had usually been an obvious heir or strong candidate and the election had been something of a formality, but when Frederick II died in 1250 there was no clear front runner, so numerous ambitious nobles eyed up the imperial crown. Through his wife, Sanchia of Provence, Richard was related to several important families in the Empire and fancied his chances, especially as he had recently been on Crusade and came back with a fine reputation. In the event it turned out the princes wanted cold hard cash in return for their votes, and Richard persuaded Henry to pay the vast sum of 28,000 gold marks only for the election to end in deadlock. Richard was crowned King of the Romans, but never managed to gain the Imperial throne.

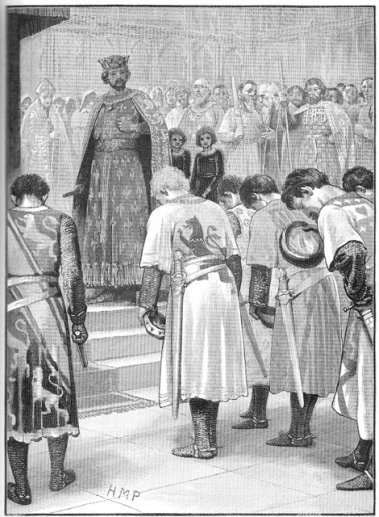

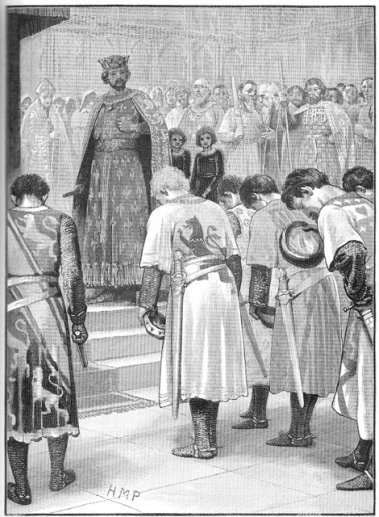

The Provisions of Oxford are presented to King Henry III by Simon de Montfort and his fellow barons in 1258.

The Kingdom of Sicily proved to be equally elusive. The Pope knew Henry wanted an inheritance for young Edmund and offered to sell him the throne of Sicily. Henry paid a massive price demanded by Pope Innocent IV, but there was a catch - or rather two. First the kingdom was to be held as a feudal fief of the Papacy, meaning that much of the wealth of the kingdom went directly to Rome. Second there was already a King of Sicily in the shape of Conrad Hohenstaufen and he had no intention of making way for Edmund. It transpired that Conrad was in dispute with the Pope, who had declared him to be dethroned though without the power to remove him from power. Henry had paid a fortune for an empty claim.

All of this cost more than Henry could afford and by 1258 he was effectively bankrupt. He summoned the barons to meet him at Oxford and asked them for more money and higher taxes. The barons agreed, but laid down strict conditions that became known as the Provisions of Oxford. Although the Provisions contained many clauses, the key ones stated that the king had to dismiss all his foreign advisers and could spend no money without the agreement of a Council of 15 barons. Henry reluctantly agreed, and swore holy oaths to implement the new rules. It was an attempt to curb the absolute power of the monarch, but only by allowing the barons a say. The rest of the country had to be content with trusting the barons to help the king appoint honest sheriffs and other officials.