Dedication

To my parents, William and Christine,

and my wife and children,

Frances, Victoria and Edward,

with all my love.

To my university tutors,

Dr David Crane and Dr Derek Todd,

to whom I am most grateful.

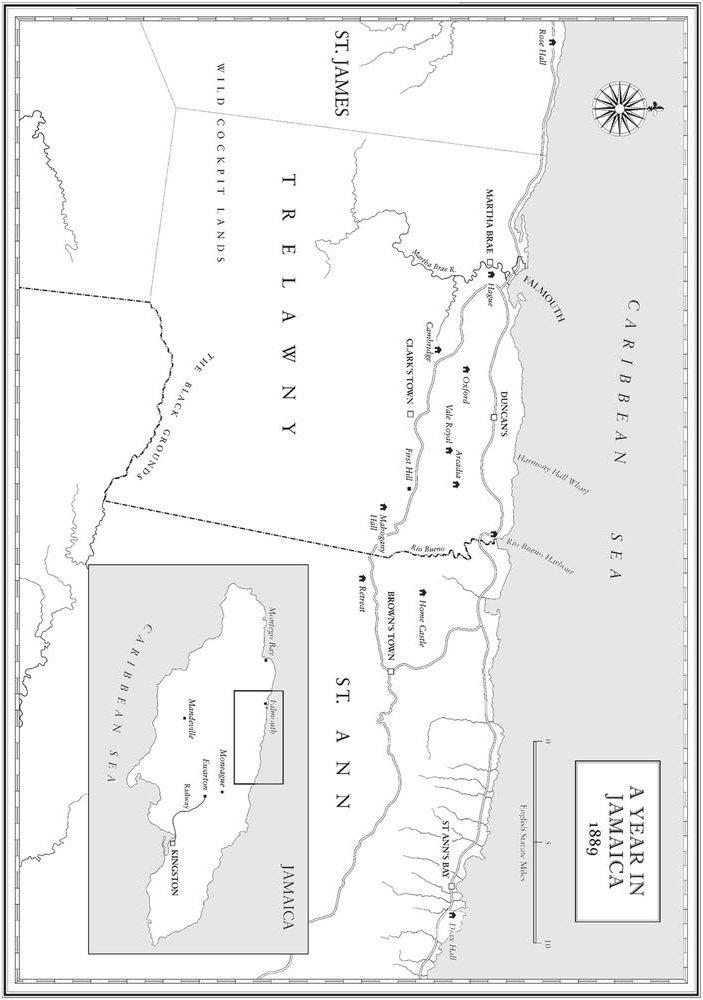

I FIRST READ my great-aunt Diana Lewess memoirs of her stay in Jamaica in 1889 in my early twenties and and was captivated by them. I always dreamed of seeing them published and finally, about forty years later, here they are. Her memoirs capture a moment in the complex social history of Jamaica in the late 1800s observed by an innocent eye. They raise and discuss difficult subjects such as sex and race without harm precisely because of this innocence. Like a colonial version of a heroine in Jane Austen, we hear this teenage Victorian trying to make sense of the complicated world the grown-ups have constructed around her, and with her we too feel the exhilaration and freedom that Jamaica offered to a girl brought up in England. Alongside her, we also try to fathom the darker currents that run through the story. I believe that these memoirs will resonate with anyone who, like me, has spent their childhood in Jamaica or indeed anyone else who has fallen under the islands spell. Although she returns to England, Diana took with her from Jamaica something which remained with her for the rest of her life.

Dianas family involvement in Jamaica began when her grandfather, William Sewell, emigrated there shortly after the abolition of slavery in 1833. Many estate owners at that time thought that sugar plantations would be uneconomic without slave labour. For example, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, whose father owned land in Jamaica, wrote on 27 May 1833 that the West Indies are irreparably ruined if the bill [ie the Act for the Abolition of Slavery] passes. In this environment, William Sewell and his partner, Simon Thomson, bought many estates at knockdown prices. A number of these were estates previously owned by the Barrett family, including Oxford, which features prominently in this book. Simon went on to marry Williams daughter, Lizzie. When he died childless, William inherited the share of the estates which he did not already own, making him a very wealthy man. Before he died in 1872, he realised that his son, Henry Sewell, was a spendthrift and left his estates in trust for his grandchildren (Diana and her siblings) with Henry as trustee. Henrys extravagance, and his ambiguous alliance with his attorney, Herr Bauer, make up one of the many intriguing strands in these memoirs.

The family connection with Jamaica continued into the 1960s and 70s, when all the estates were finally sold. My mother, who knew Arcadia in the 1950s and 60s writes:

There was a magic about Arcadia. It was a gem in a beautiful situation on a high ridge overlooking the sea with the approach though handsome gates and an avenue of royal palms. It was a striking entrance. The house was square with walls made of cut stone and the beautiful verandahs had wrought-iron balustrades. The peacocks always reigned supreme in the gardens and common around the house with their magnificent tails either trailing after them or erected. But their early morning calls were very raucous.

Dianas niece (Beatties daughter), Isabel Whitney, wrote of her visit in 1930:

Jamaica was always at the back of my brothers and my consciousness growing up, another world, yet always part of our family. Perhaps it was talked about, I dont remember. Some knowledge of our family connections must have seeped into our minds, children seem to be expected to know all the details relating to their forebears , but of course they dont because people never tell them anything that makes connections, only isolated stories, and their parents conversations are references to events long past.

The year 1930 was not only my first visit to Jamaica, it was also a visit to the past, to the turn of the century when my grandmothers rule had put a stamp on the house I was about to enter and live in for two months.

I crossed the threshold of Arcadia and found myself in 1903, the year my mother had left her Jamaican home for a different life. There is a poem by the French poet, Paul Verlaine, that expresses the feeling I experienced. A rough translation of it reads:

Having pushed open the narrow, creaking door,

I found myself walking in the little garden

Nothing had changed.

I saw everything as it once had been.

On the ground floor I passed through the rooms that had once been the home of my great-grandparents, William and Mary, in the 1860s. Williams good management and frugality had brought prosperity to his estates and he had made of Arcadia (built in 1832) a comfortable, though fairly modest, Jamaican home. The original Arcadia had been built a little further to the east along the ridge that ran 800 feet above sea level and looked down on cane fields and, beyond them, the blue Caribbean. This was the Arcadia where Lady Nugent stayed, as recorded in her diary, and quoted on page 16. [Lady Nugent was the wife of General Sir George Nugent, who was Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica from 27 July 1801 to 20 February 1806. She stayed at the original Arcadia on a tour of Jamaica with her husband on 31 March and 1 April 1802.]

Isabel would probably have been welcomed on the front steps of Arcadia by her Uncle Philip, with his pipe and dog, looking much as he does in the photograph facing page 217. For now, however, it is his sister who introduces us to their Jamaican world in 1889.

Nicholas Noble

2013

| Buckra | a white man |

| Busha | title given to manager or overseer on a sugar plantation, hence |

| Busha House | manager or overseers house on a plantation |

| Cho-Cho | a tropical vegetable, the chayote, with a bland taste |

| Picny/Piccaninny | a black child |

| Obeah | folk magic, sorcery and religious practices derived from West Africa, specifically the Igbo tribe |

| Peenies | fireflies |

March 31st 1802 we proceeded to Arcadia, where we arrived at 6. Found a party ready to receive us, and sat down to dinner before 7. To bed early. Everything here is so quiet, clean and comfortable, that we feel ourselves in Arcadia indeed.

April 1st This house is not large, but it is very neat and convenient. It stands on a high hill, overlooking the sea and a great extent of beautiful country.

From Lady Nugents Journal

I N THE YEAR 1889, when I was sixteen and my sister Beattie four years older, we were taken by our parents from our home in England to Jamaica where my father owned a number of properties and a house at Arcadia. This he regarded as his home.

My father was a compact, dignified looking man. He had a determined face and round blue eyes set wide apart. In character he was self-willed and took immediate and effective action to suppress any opposition to his wishes. People who came to his house had either to agree with him or to resign themselves to the knowledge that they would no longer be welcomed. In England I had not really noticed this characteristic. There he had been the ideal father made up of qualities which I had considered as being proper to all dear and beloved parents. At meals he had sat at the other end of the table from my mother and had fulfilled all the functions which I had imagined fathers should fulfil. He had not conformed with my slowly built up ideal in two ways alone: he had always got up late and he had never written any letters.