This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our bookspicklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1942 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2016, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

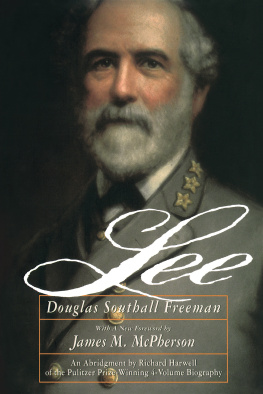

LEES LIEUTENANTS

A STUDY IN COMMAND

BY

DOUGLAS SOUTHALL FREEMAN

VOLUME THREE GETTYSBURG TO APPOMATTOX

MAPS

Battlefield of Brandy Station

Approaches to Brandy Station from Kellys Ford

Battlefield of Second Winchester and of Stephensons Depot

Routes to Carlisle, Harrisburg, Gettysburg, York

Route of Stuarts Raid from Salem, Va., to Gettysburg

Heths feelingout advance toward Gettysburg

Attack of Rodess Division near Gettysburg

Gettysburg and vicinity

Attack of Confederate right, South of Gettysburg

Attack of Confederate left on Culps Hill and Cemetery Hill

Lines of Advance of Pickett, Pettigrew, and Trimble

Advance of Second and Third Army Corps to Bristoe Station

Attack of Cooke and Kirkland at Bristoe Station

Vicinity of Auburn, where Stuart thought his force surrounded

Scene of Mine Run operations, Nov. 26Dec. 2, 1863

Vicinity of Chattanooga with reference to Longstreets operations

Regions of Longstreets operations from Wauhatchie, Tenn., to Abingdon, Va.

Terrain of WildernessSpotsylvania operations, May 421, 1864

Trench system at close of Battle of the Wilderness

Grants alternative Routes to Richmond

Lees Road from Vicinity of Parkers Store to Catharpin Road

Engagement of Confederate Cavalry and V Federal Corps

Final Confederate works at Mule Shoe or Bloody Angle

Sheridans raid and Stuarts Pursuit, May 911, 1864

Completed trench system around Spotsylvania Court House

Principal Southern railway connections of Richmond

The Richmond and Petersburg and the Petersburg and Weldon Railroads

Railroad connections of Richmond within Virginia

District between Drewrys Bluff and Petersburg

Vicinity of Louisa Court House and Trevilian Station

Sketch to illustrate first stages of Earlys Advance, June, 1864

Streams and roads between Appomattox and Nottoway Rivers

Battlefield of Monocacy, July 9, 1864

Lower Shenandoah Valley, scene of Earlys operations

Confederate infantry positions, Third Battle of Winchester

Battlefield of Fishers Hill, Sept. 22, 1864

Earlys plan for attacking Federal camps on Cedar Creek

Federal lines of battle and successive positions of VI Corps

Approaches to Southside Railroad from Dinwiddie Court House

Fort Gregg and Confederate lines South-west of Petersburg

Change of route, April 5, 1865, of Army of Northern Virginia

Vicinity of Saylors Creek, battle of April 6, 1865

Crossings of Appomattox River in vicinity of Farmville

Terrain North of Farmville

Sketch of vicinity of Appomattox Court House

Battlegrounds of the Army of Northern Virginia at end of volume

INTRODUCTION

WHEN THIS NARRATIVE opens in June, 1863, the Army of Northern Virginia had been reorganized into three Corps. Gen. R. E. Lee was conscious of the immense loss the Southern Confederacy had sustained in the death of Stonewall Jackson, and he doubtless was aware of the weight of his words when he said of his fallen lieutenant, I know not how to replace him. Hopeful that God would raise up someone in Jacksons place, Lee had to rely during a critical summer on the experience of the troops to offset the change in officers. He believed his troops invincible; he had to test newly promoted lieutenants and a veteran corps commander who had been leading a semi-independent army. To a certain point the events of June are presented, for these reasons, as a study of the state of mind of three men, Jeb Stuart, Ewell and Longstreet.

Unless it was the tone of Longstreets correspondence during the operations in front of Suffolk in the spring of 1863, nothing in the previous conduct of these officers could have prepared their commander or their subordinates for what happened in Pennsylvania. Stuart almost certainly was prompted to undertake a long raid in order to restore the reputation he felt had been impaired in the Battle of Brandy Station. Dick Ewell made an advance that equalled in dash and decision almost any achievement of his predecessor Jackson, and then, in a single hour, Ewell appeared to be a changed man. He was irresolute and unable to exercise the discretion Lees system of command allowed him. Longstreet, in turn, sought to procure an advantage of ground similar to that which he had enjoyed at Fredericksburg. He mistakenly believed that he had gained the commanding Generals approval of a tactical defensive if there had to be a strategic offensive.

These three states of mind were disclosed during the preliminaries of a campaign which brought the Army of Northern Virginia into fateful collision with its adversary at Gettysburg. The absence of Stuart, the indecision of Ewell and the sulking of Longstreet complicated adverse conditions of combat; but the traditional easy explanation of defeat at Gettysburg as the direct and exclusive result of the shortcomings of these three men cannot be sustained. On the contrary, as respects Longstreet, who often was presented as the villain of the piece, a review of all the material evidence rehabilitates him to this extent: Although he did not realize how far and how fast the Federal left had been extended southward on Cemetery Ridge during the night of July 1 and the early morning of July 2, he was correct in maintaining that the position could not be taken by assault. As Appendix II shows, the Union left from early morning was stronger than the Confederates assumed. The record definitely qualifies the familiar assertion that on the whole of the Federal left, South of the little clump of trees, more and more Federal troops arrived while Longstreet delayed his deployment. The Confederates probably were unable to see much of the lower end of the Federal position on Cemetery Ridge for the reason given in Appendix I; but the Union troops, whether visible or not, were there in strength. Almost certainly they could have repulsed any attack that could have been made on them at the earliest hour at which Longstreet could have put McLaws and Hood into action.