Copyright 2017 by Stephen W. Sears

Maps copyright 2017 by Earl McElfresh, McElfresh Map Company LLC

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-618-42825-0

Cover design by Martha Kennedy

Cover illustration: The Army of the Potomac passes in review before General George McClellan at Baileys Cross Roads, Virginia, on November 20, 1861. Watercolor by Franois dOrlans, Prince de Joinville, of McClellans staff. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

e ISBN 978-0-544-82625-0

v1.0417

For Bruce Catton (18991978)

for his many kindnesses, and

for showing how its done

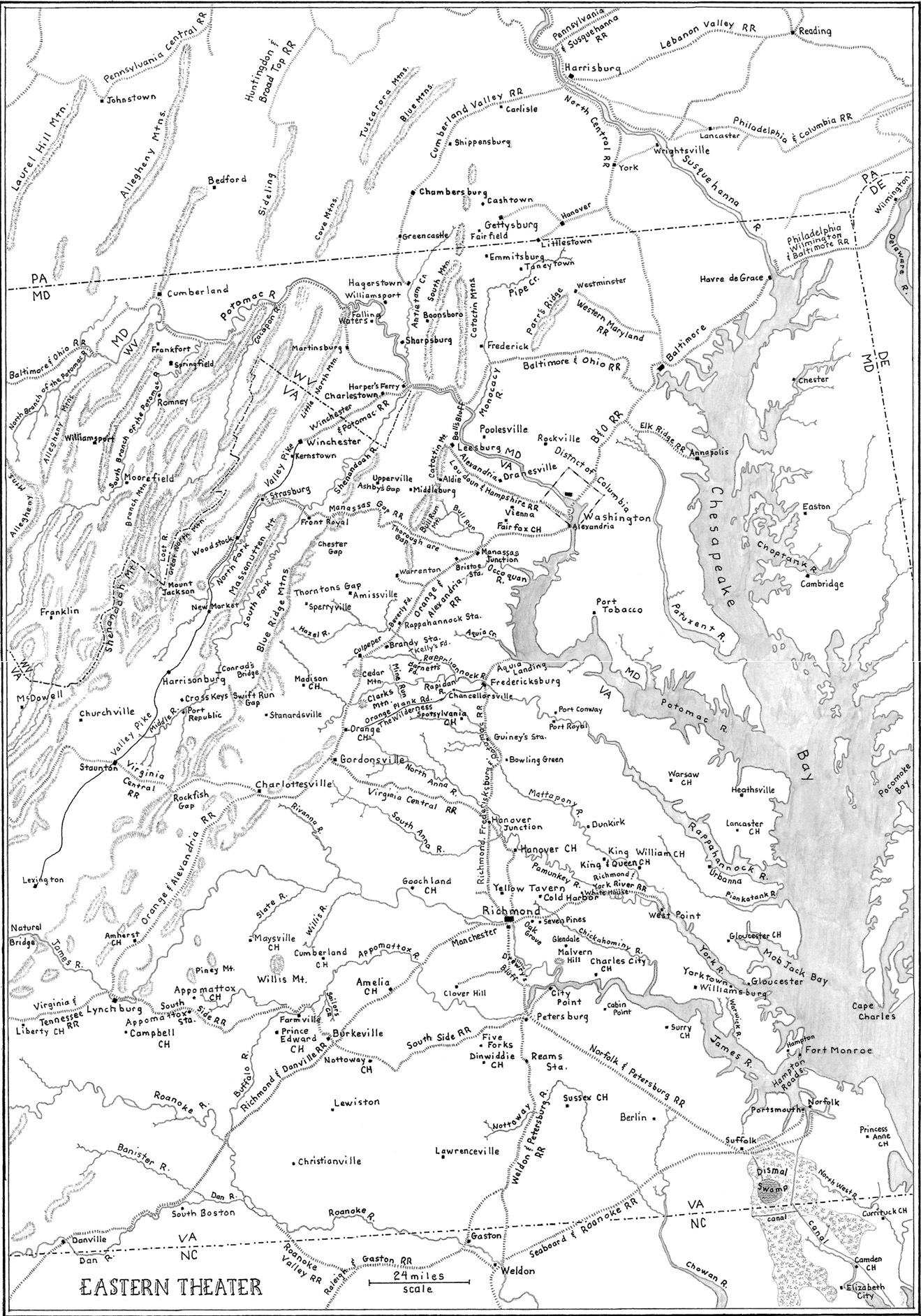

Maps

Eastern Theater |

First Bull Run 1861 |

The Virginia Peninsula 1862 |

The Seven Days 1862 |

Second Bull Run 1862 |

The Maryland Campaign 1862 |

Antietam Battlefield 1862 |

Fredericksburg 1862 |

Chancellorsville 1863 |

Gettysburg 1863 |

Wilderness & Spotsylvania 1864 |

To James River 1864 |

Siege of Petersburg 18641865 |

Introduction

IN HIS MEMOIR , General Rgis de Trobriand cast a look back at his four years in the Army of the Potomac and remarked on that armys unique wartime role. This one particular army, he wrote, simply by being based at Washington, became the army of the President, the army of the Senate, the army of the House of Representatives, the army of the press and of the tribune, somewhat the army of every one. Everybody meddled in its affairs, blamed this one, praised that one, exalted such a one, abused such a one....

This meddlingpervasive and never-endingled the Army of the Potomacs officer corps, all too often, to worry about the enemy in the rear as well as the enemy in front. On that account, these particular lieutenants of Mr. Lincolns were challenged as no other generals, North or South, in the Civil War. That challenge came atop the already stark perception that in this contest between armies of the same nation & blood (as Major Henry L. Abbott put the matter), it was command that made the difference.

In spring 1861 General-in-Chief Winfield Scott collected those at-hand regular-army officers who had not joined the secessionists and put them under Irvin McDowell in defense of the capital. Soon enough routed at First Bull Run, McDowells Army of Northeastern Virginia gave way to a name change and a new commander, George Brinton McClellan. McClellan played a major role picking generals for his newly christened Army of the Potomac, and many of his choices were in their turn McClellanized, a contagious disease diagnosed by critics as bad blood and paralysis.

The era of McClellan, lasting until November 1862, witnessed the largest campaign of the war, on the Virginia Peninsula, the bloodiest single day in the nations history, at Antietam, and in between the brief reign of General John Pope, who blundered his way to the Potomac armys second defeat at Bull Run. It was an era when generals, from army headquarters down through corps, division, and brigade, indulged themselves in the politics of war. Historian Bruce Catton called it the Era of Suspicion. The press was cosseted and leaked to. The Radical Republican congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War grilled allegedly Democratic generals for supposedly disloyal acts. Among the McClellanized there was talk around the campfires and in headquarters tents of intrigues and betrayals and coups.

To be sure, in the fighting on the Peninsula and at Second Bull Run and at Antietam, many of McClellans and Popes subordinate generals fought capably and some brilliantly. The defeats and doubtful outcomes were due to the generals commanding (and due as well to the best general on all these fields, Robert E. Lee).

Lincolns decision to replace McClellan with Ambrose Burnside marked the apex of the Era of Suspicion. Burnside was not appointed for his command skills (which he himself loudly disclaimed) but because he was thought to be apolitical and would cushion the effects of McClellans dismissal. Burnsides subsequent dismal fall at Fredericksburg was not in the least cushioned by his officer corpswhich officer corps then, in spring 1863, openly rebelled against Joe Hooker in the aftermath of the defeat at Chancellorsville.

In tracing the saga of the high command of the Army of the Potomac, the darkling doldrums of McDowell, McClellan, Pope, Burnside, and Hooker give way at last to comparatively sunny uplands when George Meade and then U. S. Grant take command. The road from Gettysburg to Appomattox would prove to be marked by brutal casualties and its share of command lapses and blunders in the officer corps, yet talk of disloyalty and conspiracies and coups to undercut the army and its generals was largely absent. Politicking would reemerge in securing Lincolns reelection in 1864, but by this time the Potomac army had become Mr. Lincolns army; the politics were tolerated for a vital cause.

The high command that closed the war in April 1865 was a world apart from the high command that opened the war. This had become a largely self-taught army led by volunteer officers from civilian life. Four years of fighting cost twenty-one of its generals their lives, but somehow, through trial and tribulation unimagined, the Army of the Potomac kept its identity and its purpose and its resolution steadfast until final victory.

Civil War Seems Inevitable...

GENERAL SCOTT SEEMS to have carte blanche. He is, in fact, the Government, and if his health continues, vigorous measures are anticipated. So wrote Edwin M. Stanton, late attorney general in James Buchanans cabinet (and future secretary of war in Abraham Lincolns cabinet), in a letter to the former president dated May 16, 1861. The subject of this observation was Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, whose arching self-esteem would surely have brought forth an imperial nod of agreement at Stantons characterization.

The notion that General Scott was the Government was Stantons insight that the army appeared to be the power in the landor at least in the Northern half of the landand therefore to one and all Scott, as general-in-chief, was the army.

In fact Scotts role during the secession crisis and now the war crisis had traced an erratic course. But then Winfield Scott was by nature erratic. His heroics in uniform went back to the battles of Chippewa and Lundys Lane in the War of 1812, and the regular army he afterward nourished showed its mettle under his brilliant command in the War with Mexico. He was appointed army general-in-chief in 1841 and brevetted lieutenant general in 1855. In the meanwhile Old Fuss and Feathers squabbled publicly with one fellow general or another, ventured disastrously into presidential politics as the Whig partys candidate in 1852, and in a fit of pique moved army headquarters from Washington to New York so he would not have to associate with President Franklin Pierce, who had defeated him so handily. Scott remained implanted in New York during the tenure of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, with whom he carried on a vitriolic feud.

As the election of 1860 approached, the South was swept with blazing pledges of secession and disunion should Abraham Lincoln and the Black Republicans gain the presidency. Because the fatal split of the Democratic party made that outcome a virtual certainty, General Scott concluded it was time and past time for statesmanship to prevail. He regarded himself, in his seventy-fifth year, as a senior statesman. He would offer his thoughts on the impending national crisis.

Next page