HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY Boston/New York 2003

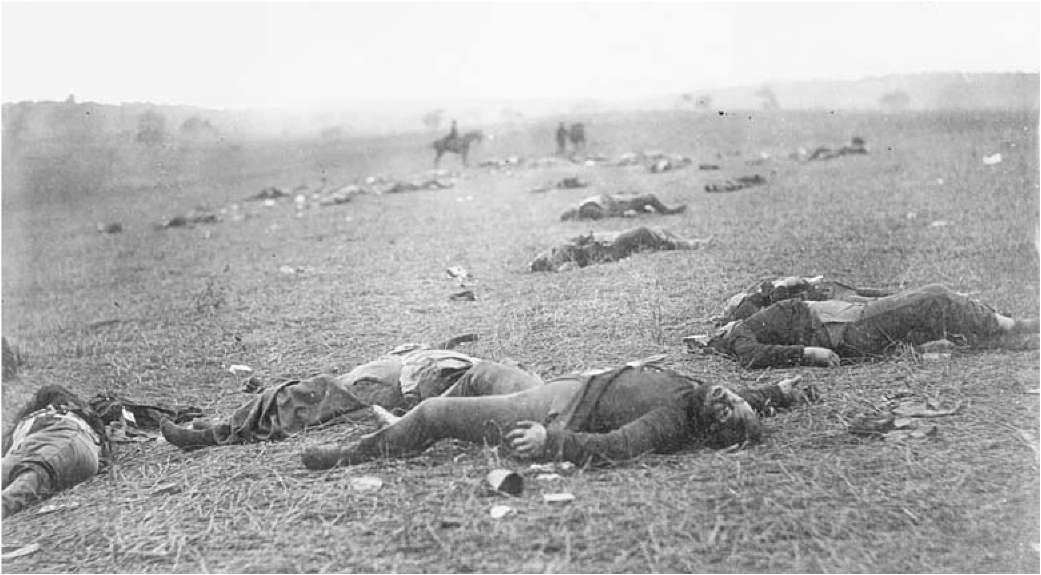

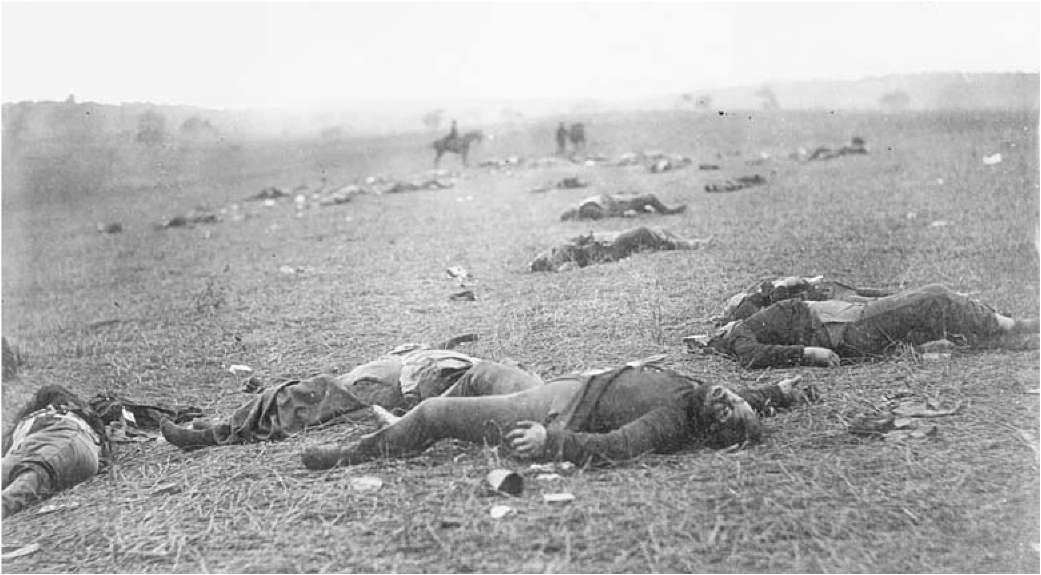

A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, July 1863

Copyright 2003 by Stephen W. Sears

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South,

New York, New York 10003.

Visit our Web site: www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sears, Stephen W.

Gettysburg / Stephen W. Sears.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-395-86761-4

1. Gettysburg, Battle of, Gettysburg, Pa., 1863. I. Title.

E475.53.S43 2003

973.7'349dc21 2002191259

Printed in the United States of America

QUM 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Book design by David Ford

For Sally, in loving memory

Contents

List of Maps

Introduction

1 We Should Assume the Aggressive

2 High Command in Turmoil

3 The Risk of Action

4 Armies on the March

5 Into the Enemy's Country

6 High Stakes in Pennsylvania

7 A Meeting Engagement

8 The God of Battles Smiles South

9 We May As Well Fight It Out Here

10 A Simile of Hell Broke Loose

11 Determined to Do or Die

12 A Magnificent Display of Guns

13 The Grand Charge

14 A Long Road Back

Epilogue: Great God! What Does It Mean?

The Armies at Gettysburg

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Maps

Brandy Station, June 9, 1863

The March North, June 319, 1863

Winchester, June 1315, 1863

The Armies, June 28, 1863

The March North, June 2930, 1863

Roads to Gettysburg, July 1, 1863

Gettysburg: A Meeting Engagement, July 1, 10:00 A.M.

Gettysburg: First Blood, July 1, late morning

Gettysburg: Battle for McPherson's Ridge, July 1, afternoon

Gettysburg: Federal Defeat, July 1, late afternoon

Gettysburg: Longstreet's Offensive, July 2, 4:00 P.M.

Gettysburg: Longstreet's Attack, July 2, late afternoon

Gettysburg: Battle for Little Round Top, July 2, late afternoon

Gettysburg: Anderson's Attack, July 2, late afternoon

Gettysburg: Ewell's Attack, July 2, evening

Gettysburg: Johnson's Attack, July 3, morning

Gettysburg: The Artillery, July 3

Gettysburg: Pickett's Charge, July 3, afternoon

The Retreat, July 514, 1863

Maps by George Skoch

Introduction

CAPTAIN SAMUEL FISKE, 14th Connecticut, soldier-correspondent for a New England newspaper, seated himself in the shade of an oak tree on a Pennsylvania hilltop and prepared "to task my descriptive powers" to report the fighting he expected would open at any moment. It was midafternoon, July 2, 1863. The enemy, wrote Fiske, "are arrogant and think they can easily conquer us with anything like equal numbers. We hope that in this faith he will remain, and give us final and decisive battle here...."

Just a day earlier, in the Confederate camps a mile or so to the west, a foreign visitor, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur J. L. Fremantle of Her Majesty's Coldstream Guards, had observed in the Rebel army that same arrogant attitude. In his journal Fremantle made note that "the universal feeling in the army was one of profound contempt for an enemy whom they have beaten so constantly...."

What happened in the three days of Gettysburg, July 13, 1863, was in some measure a result of that arrogance. To be sure, there was good reason for Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia to be contemptuous of the Yankees. At Fredericksburg the previous December they had beaten them easily, and two months ago at Chancellorsville they had beaten them again, less easily this time but against longer odds. General Lee marched into Pennsylvania in the confident expectation of winning a third battlebut now in the enemy's country and with the promise of a considerably more decisive outcome.

The Confederacy was greatly in need of such a victory in that early summer of 1863. Vicksburg was besieged and almost certainly beyond saving, thereby endangering the entire Confederate position in the western theater. Lee gained Richmond's approval for the Pennsylvania expedition not in any expectation of changing matters at Vicksburg, but rather with the hope of offsetting disaster there by a compensating victory in the Eastparticularly a victory of real consequence won in the Northern heartland. The stakes were therefore high indeed.

Lee's Pennsylvania gambit, of course, failed, and failed dramatically, and the Army of Northern Virginia had to beat a hasty retreat back across the Potomac. For General Lee, Gettysburg was a defining defeat, and in the fourteen decades since 1863 much effort has been expended to try and explain it. For the most part Lee succeeded in shielding himself and his wartime actions (as the poet Stephen Vincent Benet put it) "From all the picklocks of biographers." Yet at Gettysburg Lee's actions were uniquely uncharacteristic of him and they spoke volumes. Why he did what he did can therefore be deciphered.

With so much attention paid to the losers, and for so long, it is easy to lose sight of the victors. When General Pickett was asked to explain the failure of his charge, he famously remarked, "I think the Union army had something to do with it." George Gordon Meade and the men of the Army of the Potomac came to Gettysburg without contempt for their opponents, and as a consequence they never deceived themselves about the impending battle.

General Meade's accomplishments on the Gettysburg battlefield were remarkable, all the more so considering that July 1 was his fourth day of army command. As it happened, Meade fought the battle defensively just as he intended (if not in the place he intended). His fighting men were as remarkable as he was. At Gettysburg, wrote Captain Fiske on July 4, "the dear old brave, unfortunate Army of the Potomac has redeemed its reputation and covered itself with glory...."

Gettysburg proved to be both the largest battle fought during the war and the costliest. The two armies between them lost more than 57,000 men during the Pennsylvania campaign, including some 9,600 dead. Repelling the Confederates' offensive and stripping the initiative from General Lee were the immediate consequences. The longer-term effects would not be so easily seen or felt; still, Gettysburg marked the turning point of the war in the East. As Winston Churchill said of El Alamein, another turning point in another war, "Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning."

1. We Should Assume the Aggressive

JOHN BEAUCHAMP JONES, the observant, gossipy clerk in the War Department in Richmond, took note in his diary under date of May 15, 1863, that General Lee had come down from his headquarters on the Rappahannock and was conferring at the Department. "Lee looked thinner, and a little pale," Jones wrote. "Subsequently he and the Secretary of War were long closeted with the President." (That same day another Richmond insider, President Davis's aide William Preston Johnston, was writing more optimistically, "Genl Lee is here and looking splendidly & hopeful.")

However he may have looked to these observers, it was certainly a time of strain for Robert E. Lee. For some weeks during the spring he had been troubled by ill health (the first signs of angina, as it proved), and hardly a week had passed since he directed the brutal slugging match with the Yankees around Chancellorsville. Although in the end the enemy had retreated back across the Rappahannock, it had to be accounted the costliest of victories. Lee first estimated his casualties at 10,000, but in fact the final toll would come to nearly 13,500, with the count of Confederate killed actually exceeding that of the enemy. This was the next thing to a Pyrrhic victory. Chancellorsville's costliest single casualty, of course, was Stonewall Jackson. "It is a terrible loss," Lee confessed to his son Custis. "I do not know how to replace him." On May 12 Richmond had paid its last respects to "this great and good soldier," and this very day Stonewall was being laid to rest in Lexington. Yet the tides of war do not wait, and General Lee had come to the capital to try and shape their future course.

Next page