Copyright 1992 by Stephen W. Sears

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Sears, Stephen W.

To the gates of Richmond : the peninsula campaign / Stephen W. Sears. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-89919-790-6

1. Peninsula Campaign, 1862. I. Title.

E473.6.S43 1992

973.7'32dc20 92-6923

CIP

e ISBN 978-0-547-52755-0

v1.1014

Front map: An 1861 lithograph Panorama of the Seat of War, drawn by John Bachmann, offers a birds-eye perspective on the eastern theater. The two capitals, Washington and Richmond, are at right center and left center, respectively. Fort Monroe, at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula, is at lower left.

Print Collection, New York Public Library

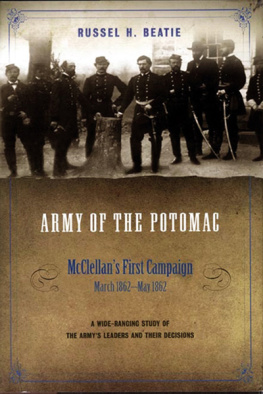

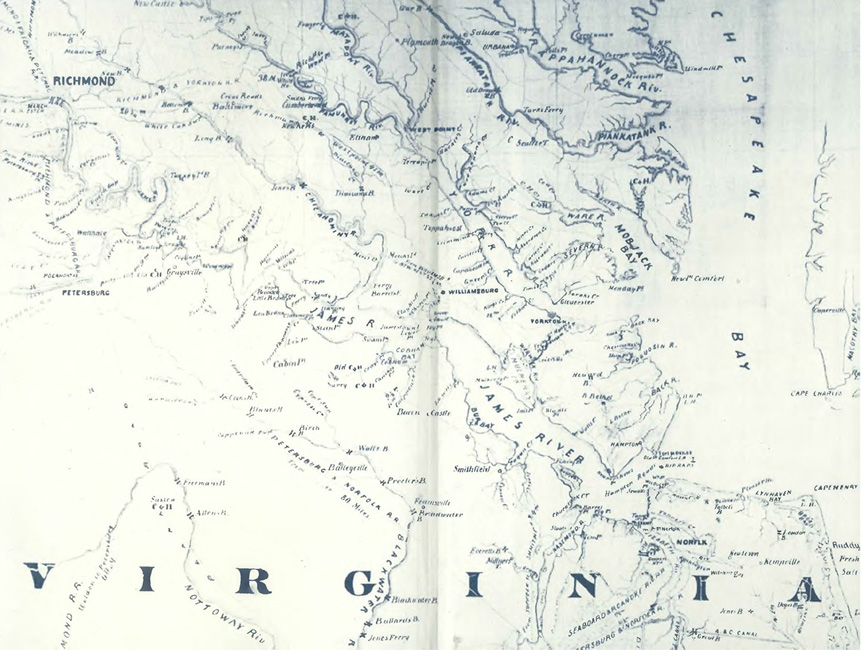

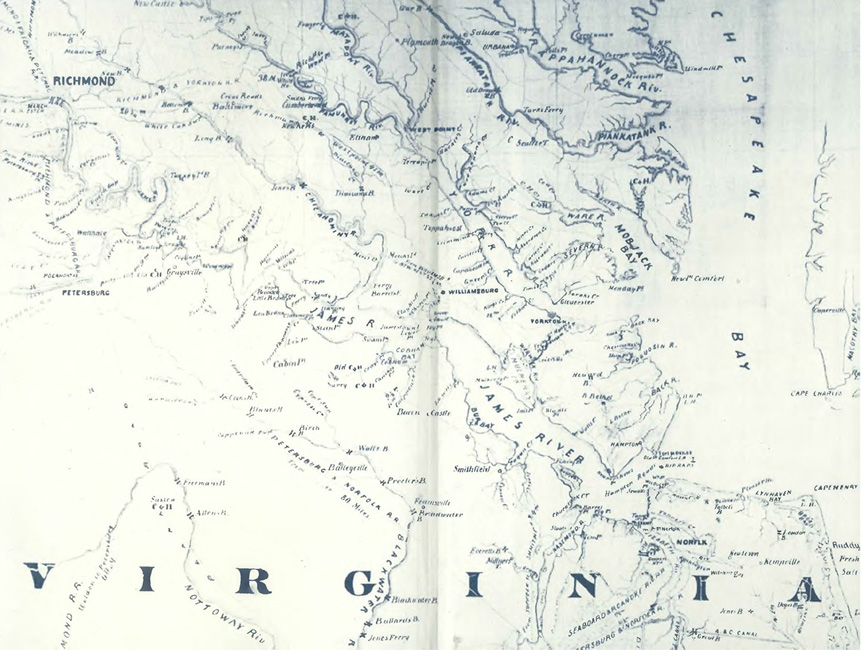

Back map: Colonel Thomas J. Cram, a topographical officer at Fort Monroe, compiled this manuscript map of southeastern Virginia early in 1862. It was on this section of Crams map that General McClellan planned his Richmond campaign, initially to begin from Urbanna (top right center), then shifted to Fort Monroe (lower right).

Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress

For My Mother and Father

Maps

Siege of Yorktown, April 5May 3, 1862

Battle of Williamsburg, May 5, 1862

The Shenandoah Valley Theater, MarchJune 1862

Advance to the Chickahominy, May 630, 1862

Battle of Hanover Court House, May 27, 1862

Seven Pines as Planned, May 31, 1862

Seven Pines as Fought, May 31, 1862

Battle of Seven Pines, May 31, 1862

June 1, 1862

Stuarts Ride Around McClellan, June 1215, 1862

Jacksons March, June 2425, 1862

The Seven Days: Battle of Oak Grove, June 25, 1862

The Seven Days: Advance to Mechanicsville, June 26, 1862

The Seven Days: Battle of Mechanicsville, June 26, 1862

The Seven Days: Advance to Gainess Mill, June 27, 1862

The Seven Days: Battle of Gainess Mill, June 27, 1862

Battle of Savages Station, June 29, 1862

The Seven Days: Battle of Glendale, June 30, 1862

The Seven Days: Battle of Malvern Hill, July 1, 1862

Introduction

T HE ENEMY are at the gates. Who will take the lead and act, act, act? the Richmond Dispatch pleaded on May 16, 1862. The massive Federal armysome compared it to Napoleons Grande Armewas indeed very nearly at Richmonds gates that day. Soon enough Yankee soldiers could see the citys spires and hear its clock bells chime the hours. Citizens and soldiers alike believed the climax of the war was at hand.

The Peninsula campaign of 1862the march to the gates of Richmondwas the largest single campaign of the Civil War. More mena quarter of a million of themand more weapons of war were assembled on the Virginia Peninsula for this battle for the capital of the Confederacy than for any other operation of the war. Contemporaries called it, aptly enough, the grand campaign.

More than its size generated the sense of something special about the Peninsula campaign. In his journal the Comte de Paris, pretender to the French throne, recalled how anxious he was to join General McClellans staff: We counted upon seeing the campaignbecause of course there was only supposed to be one campaign and that one both immediate and short. The principal army of the Federal government was to march on Richmond and fight the principal army of the Confederacy there, and if the Federals were victorious, as it was supposed they would be, the rebellion would be over.

From late March to late June of 1862 the two armies sparred and maneuvered and battled their way up the Peninsula toward the capital. At Yorktown they went to ground in a month-long siege, wielding the latest and largest weapons of war. At Williamsburg and Seven Pines there were savage battles in the woods and clearings. The armies faced each other across the Chickahominy swamps. The campaign employed the newest ways to make warironclad warships and 200-pounder rifled cannon and the battlefield telegraph and aerial reconnaissance.

At last the plea of the Dispatchs editor was answered. Robert E. Lee, taking command of the Army of Northern Virginia, proceeded to lead and act, act, act with a vengeance. Lees offensive, the Seven Days Battles, witnessed in a week-long struggle some of the bloodiest fighting of the war, and drove the grand campaign to its climax. When the campaign was finally over, one of every four men engaged in it was dead, wounded, or missing.

The historical record of the Peninsula campaign is a uniquely rich one. Only a fraction of the men who fought there had ever fought before. These men going to war for the first time were determined to make a record of their experience, and Yankees and Rebels in remarkable numbers kept diaries and journals and wrote letters home. The Peninsula campaign was not only the largest of the war but the one most written about by those who fought it. Their eyewitness accountsmost of them used here for the first timeadd a special color and texture to the story.

Corporal Sidney J. Richardson of the 21st Georgia spoke for thousands of men on both sides when he wrote home after the Seven Days, The canons roared like perpetual thunder, the balls bombs shells whistling in the air cutting down trees killing men horses and every live thing they hit.... It was a horrible time, the worst time I ever saw. It was a horrible time, and it changed the course of the war.

PART I

THE GRAND CAMPAIGN

I shall soon leave here on the wing for Richmondwhich you may be sure I will take.

M AJOR G ENERAL G EORGE B. M C C LELLAN

M ARCH 16, 1862

Seven Days to Decision

A T TEN OCLOCK on the clear, cold morning of Friday, March 7, 1862, an even dozen brigadier generals assembled at army headquarters on Pennsylvania Avenue at Jackson Square in Washington. To a man they were startled to be told that forthwith they would act as a council of war. None had played the role before. Only three or four had even a vague notion of what plans the army might be considering, for General McClellan was notoriously secretive about his intentions. They had supposed they were being called to headquarters that morning to receive orders for an attack on the Confederate batteries blockading the Potomac below the capital. Instead, without preamble, they learned they would be deciding how and where and when to launch the Army of the Potomacs grand campaign to end the war.

A council of war had in fact been the furthest thing from General McClellans mind when he scheduled the meeting the day before. The newspapers called him the Young Napoleon, and like the first Napoleon he had only contempt for generalship by committee. At age thirty-five George Brinton McClellan was at once the youngest and the senior major general in the United States army. He had commanded the Army of the Potomac for seven and a half months now, and, as general-in-chief, all the Unions armies for the last four of those months, and he appeared well cast for the part: short and broad-shouldered, with a quick eye and a jaunty confidence, he never displayed anything less than a commanding presence. He was tremendously popular with his soldiers, but in recent months his popularity with major figures in the government had plummeted almost to the vanishing point. Once he had been the toast of Washington. Now opponents in growing numbers noisily snapped at his heels.

Next page