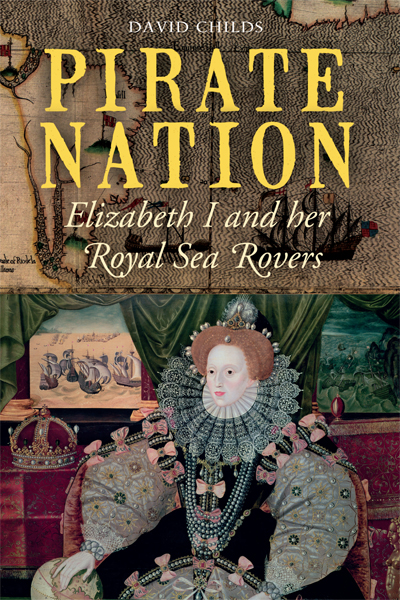

Copyright David Childs 2014

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Seaforth Publishing,

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 84832 190 8

eISBN 9781848322936

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

The rights of David Childs to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Exchange Rates

1 in 1600 would be worth about 130 in 2014.

***

There were 20 shillings to the pound and twelve pennies to the shilling.

One crown was worth five shillings.

***

(approximate for the period)

One gold ducat was worth seven shillings.

One silver ducat was worth 5s 6d.

One pesos de oro was worth 8s 3d.

One real was worth six pennies.

***

34 maravedis = one real.

8 reals = one peso.

One pound weight (lb) = 0.45 kilograms.

One hundredweight (cwt) = 50.8 kilograms.

One foot = 30 centimetres.

CHAPTER 1

Protestants in Pursuit of Profit

I write not this in favour of piracies, for I hate all pirates mortally.

Lord Burghley, Lord Treasurer, November 1590

For two hundred years, the least safe track along which an Englishman could travel upon his lawful occasion was the sea lane that lay between Ushant and London Bridge, along which, as if in sea-thickets, pirates waited to snag in their barbs all whom appeared weaker than themselves.

This barbed infestation arose because exploitable gaps existed in the surveillance of the sea by the forces of law and order. Such piracy took root because it was nurtured by sections of society ashore, including many in the magistracy who, charged with its eradication, dealt in maritime malfeasance and took an active role in its ordering and establishment while protecting those engaged in the trade. It grew stoutly during the last two decades of the sixteenth century because Queen Elizabeth I, her Lord Admiral and most of her Privy Council, with the honourable exception of William Cecil, Lord Burghley, profited from supporting the leading practitioners of this illegal trade.

Each level of growth had a geographical locus. Thus a local rogue turned rover might land and dispose of his piratical gains under cover of darkness near the harbour which was his home. At county level, a crooked but influential member of the gentry, such as the local vice admiral, could make it known that he was prepared to turn a blind eye to such activities at a price, or even sponsor a few ships and seamen of his own. At this stage of growth the Crown, when so minded, attempted to cauterise the activity, although there were always those in authority, such as the Lord Admiral, who controlled both the navy and the Admiralty Court, who could covertly condone that which they were charged to condemn. The result was that the pruning hooks of legality were handled with such discretion that those dispatched by both sea and land to root out piracy wielded their secateurs in a lackadaisical manner only snipping with full force on those least able to offer rich rewards in their defence. No effort was ever made to constrain those who returned with the most golden fruits from further afield, regardless from whose orchard they had been snatched.

By the mid sixteenth century England had earned her epithet of a nation of pirates, but in the quarter century that closed with Elizabeths death in 1603, the country turned from being a nation of pirates into a pirate nation; a state whose own ruler was identified as a pirate queen who (along with most her advisers, favourites and legal practioners) was a beneficiary of piracy.

In this environment, piracy meaning robbery at sea came to refer to several different ways in which merchandise could be removed from ships by force. At the Jolly Roger, skull-and-crossbones end, it included the swashbuckling exploits of many an opportunist, as well as the activities of half-starved men struggling to survive by robbing little of value from their fellow seagoers. Hundreds of lowly pirates plied this trade in comparative obscurity, unless they were captured, tried and, lacking influential friends, hanged at the Execution Dock at Wapping between the high and low water marks, a muddy strand that came within the jurisdiction of the Lord High Admiral. Their activities indicated a lack of law enforcement, but not the financial and moral vacuum at the very top which was essential for the careers of a few of the most successful pirates to flourish.

For such men to thrive they needed both the challenge of cargoes worth capturing and security from prosecution. One of the problems with the persecution of piracy arose because many of these crimes took place beyond the jurisdiction of the nations whose citizens were involved, ie on the high seas. Pirates were in this respect natural outlaws, roving as satellites beyond the gravitational pull of the Admiralty and its officials, whose response to pirates returning to land depended much more on the political and financial fallout from their activities rather than the legality of their actions making many of them outlaws, but not outcasts.

To manage this lawlessness one league out from land, states recognised a system of compensation whereby a merchant could reclaim the value of plundered goods from the nation of the pirate. This was achieved through the issue, by a state or convenient pretender, of letters of reprisal (or marque in French), often valid for just six months, which granted to the wronged party the right to board vessels linked to the perpetrator by port of origin, nation or even religion, and seize goods up to the assessed value of that which had been taken. When well-ordered the system worked: in 1546 the owners of Kathryn of Bristol fell in with a Breton ship whose owner owed them 100. Coming alongside, they persuaded the master to be escorted to St Davids where without compulsion, the Breton delivered him 11 tun of wine, priced 22, and 9 ton of salt, price 6, as parcel of that 100. The cargo claimed by Kathryn of Bristol represented the typical, everyday, boring bulk freight that was so frequently seized piratically in the first half of the sixteenth century. The fact that many considered it worthwhile risking their necks to seize a barrel of salted herring and some wax candles says more about the social deprivation that existed in many a coastal town and village than it does about a natural streak of thievery running through the veins of English seamen. Besides which, the latter quarter of the sixteenth century was a period of dearth, when food taken at sea became a form of famine relief. Yet far offshore, a new type of cargo was now being carried across the oceans creating new opportunities and fresh temptations.

This sea-change into something rich, if not strange, had made itself apparent the year before the successful conclusion of Kathryn s claim. On 1 March 1545, Robert Reneger, acting with the invalid authority of a letter of reprisal issued two years earlier, seized the carrack San Salvador , near Seville, whence she was returning from a voyage to New Spain laden with gold and other goods to the value of 4,300 (560,000 today). However exaggerated Renegers original claim for compensation had been, there is no chance that it could have amounted to more than a single digit percentage of what he saw stowed in the hold of San Salvador . He brought it home where, whatever his desire, it was so valuable that he had to involve the Crown in its disposal. The treasure was taken to the Tower, but not so Reneger who, to the intense annoyance of the imperial ambassador, instead of being punished like a pirate, was treated like a hero.