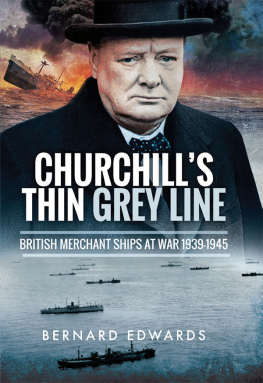

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Pen & Sword Maritime

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Martin Mace and John Grehan, 2014

ISBN 978 1 78346 204 9

eISBN 9781473837355

The right of Martin Mace and John Grehan to be identified as Authors of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local

History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact:

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

I NTRODUCTION

At the outbreak of the Second World War the seas were the highways of the world. Almost all intercontinental trade around the globe was conducted by ships, great and small. Protecting Britains maritime activities was the Royal Navys primary role, in peace and in war, just as it was her enemies objective to disrupt those activities.

With the commencement of hostilities in 1939, the Royal Navy sought to destroy the German Navys ability to interfere with Britains merchant shipping. The main threats, it was believed, came from submarines and surface raiders. In terms of the latter, it was the powerful German capital ships which were of the greatest concern to the Admiralty.

Enormous effort, in terms of time and resources, was put into neutralising these ships, and the stories of their destruction are some of the most exciting tales of the war. The first of these was the operation to sink the German Deutschland-class heavy cruiser Admiral Graf Spee , which culminated in the Battle of the River Plate in December 1939.

Every movement by the British and Commonwealth ships that chased and engaged Admiral Graf Spee is recorded in Rear Admiral H.H. Harwoods report. This culminated with these words written on Sunday, 17 December 1939, as the Royal Navy warships sailed past the burning wreck of Admiral Graf Spee in the estuary of the River Plate: It was now dark, and she was ablaze from end to end, flames reaching almost as high as the top of her control tower, a magnificent and most cheering sight.

Harwood also included with his despatch a list of observations drawn from the fighting with Admiral Graf Spee . This had been the first battle with a capital ship that the Royal Navy had been engaged in since the end of the First World War. Possibly his most enlightening comment was on the performance of Admiral Graf Spee s captain, Kapitn zur See Hans Langsdorff.

When the pursuing British warships were spotted by Admiral Graf Spee , the German cruiser immediately turned towards them at full speed. This was quite illogical. Admiral Graf Spee s 11-inch guns far outranged the 8-inch and 6-inch guns of the British cruisers. With a maximum speed of almost thirty knots, Admiral Graf Spee was only marginally slower than the British cruisers and so could have kept out of their range for a considerable time, enabling its heavier guns to inflict serious damage on the pursuers. But by closing the distance so quickly, the guns of the British cruisers were soon brought into range. Though Admiral Graf Spee struck and disabled HMS Exeter and put HMS Ajax s aft gun turrets out of action, by the time the battle was discontinued, Admiral Graf Spee had been hit approximately seventy times.

As is well known, the damage caused to the German cruiser induced Langsdorff to put into Montevideo, the capital city of neutral Uruguay, for repairs. It was the end of her operational career, in which she accounted for 50,089 tons of Allied shipping.

If the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 was a shock to the USA, the sinking of the King George V-class battleship HMS Prince of Wales and Renown-class battlecruiser HMS Repulse , was an equally devastating event to Britain. A report on this seemingly inexplicable occurrence was compiled by Vice-Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton, Commander-in-Chief, Eastern Fleet, on 17 December 1941, but not published until 26 February 1948.

The two ships had been investigating a possible landing by the Japanese at Kuantan, Malaya, when they were attacked by Japanese aircraft as they returned to their base at Singapore. The first attack resulted in just one bomb striking HMS Repulse . But this was followed by an attack by seventeen torpedo bombers and one of their torpedoes hit the outer port propeller of Prince of Wales where it exited the hull.

Further torpedo strikes were made on both ships and, inevitably, both were sunk. The despatch by Layton is supplemented by that of Captain W.G. Tennant of Repulse , who was the senior officer to survive the sinking.

There are also a number of interesting appendices, one of which is a report from Flight Lieutenant Vigors, whose 453 Squadron was involved in the rescue of some of the crews: I had the privilege to be the first aircraft to reach the crews of the PRINCE OF WALES and the REPULSE after they had been sunk. I say the privilege, for during the next hour while I flew around low over them, I witnessed a show of that indomitable spirit for which the Royal Navy is so famous. I have seen a show of spirit in this war over Dunkirk, during the Battle of Britain, and in the London night raids, but never before have I seen anything comparable with what I saw yesterday. I passed over thousands who had been through an ordeal the greatness of which they alone can understand, for it is impossible to pass on ones feelings in disaster to others.

Even to an eye so inexperienced as mine it was obvious that the three destroyers were going to take hours to pick up those hundreds of men clinging to bits of wreckage, and swimming around in the filthy oily water. Above all this, the threat of another bombing and machine-gun attack was imminent. Every one of those men must have realised that. Yet as I flew around, every man waved and put his thumb up as I flew over him.

After an hour, lack of petrol forced me to leave, but during that hour I had seen many men in dire danger waving, cheering and joking as if they were holiday-makers at Brighton waving at a low-flying aircraft. It shook me for here was something above human nature. I take off my hat to them, for in them I saw the spirit which wins wars....

The next published despatch is that of Admiral Sir John Tovey. This provides an account of the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck . This famous operation requires no introduction, but what is provided in this despatch are precise details of every move by all the ships involved (and, of course, the aircraft) details that can only be found in a report of this nature, which runs to more than 20,000 words.

With the demise of Bismarck , attention turned to the German capital ship Scharnhorst , which is variously described as a battleship and battlecruiser. Though less well known than the Battle of the River Plate and the sinking of Bismarck , the Battle of the North Cape was a classic capital ship engagement and the last of its kind between British and German warships.