First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright John Grehan and Martin Mace, 2014

ISBN 978-1-78159-328-8

eISBN 9781473838185

The right of John Grehan and Martin Mace to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All! rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset by Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire HD4 5JL.

Printed and bound in England by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, and Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

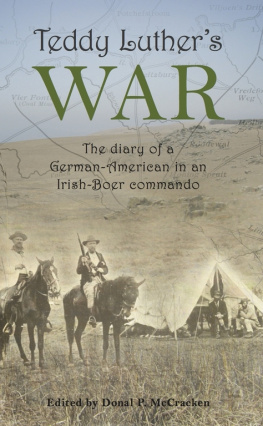

Like so many conflicts that Britain has been involved in, its Army was ill-prepared for war when the fighting broke out in South Africa in October 1899. The conflict that ensued is commonly referred to as the Boer War, but is more properly named the Second Boer War.

Despite the warnings from many senior figures in South Africa, and threats from the President of the Transvaal, Paul Kruger, Britain had only 14,750 regular soldiers to defend the colonies of Natal and the Cape. The Boers, from the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, could count 50,000 well-armed mounted infantry in their ranks.

The complex origins of the war resulted from more than a century of conflict between the Boers and the British, as well as the deteriorating relationship between the two sides in the years since the end of the First Boer War (was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881). That deterioration spilled over into outright war on 11 October 1899.

On that day the Boers mounted a surprise offensive into the British-held Natal and Cape Colony areas. With no regular army units, the Boers had no problems with mobilisation. As with the First Boer War, since they were generally a civilian militia, each Boer wore what he wished, usually his everyday dark-grey, light-grey, neutral-coloured, or earthtone khaki farming clothes often a jacket, trousers and slouch hat. The exception was the Staatsartillerie (Afrikaans for States Artillery) of the Transvaal and Orange Free State republics which wore light green uniforms.

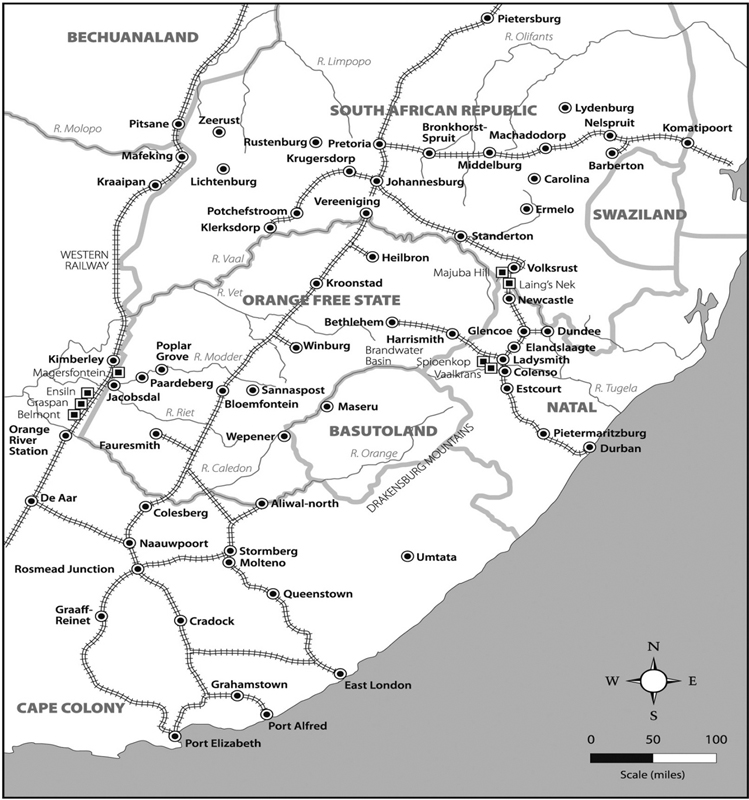

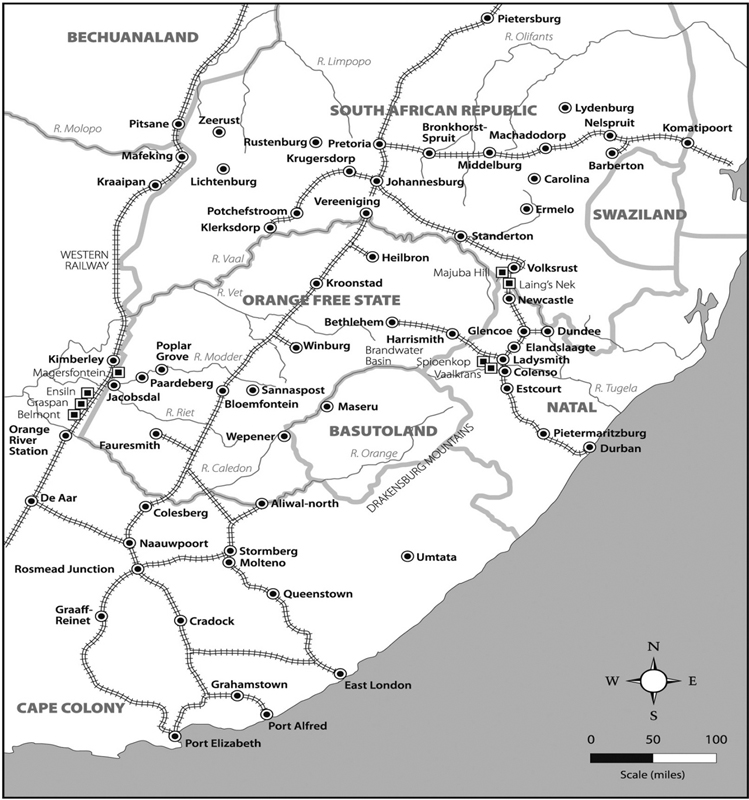

Moving rapidly across the veldt, the Boers drove the British Natal Field Force into Ladysmith. Other British forces were besieged in Kimberley and Mafeking. The sieges of these places tied down a considerable proportion of the Boer forces. It was a mistake. The great advantage which the Boer troops had over the conventional British soldiers was their speed and manoeuvrability over terrain they knew intimately. By tying down their men in protracted, stagnant sieges the Boers threw away those advantages. Their opportunity to gain a quick victory was lost and gave Britain a second chance.

Nevertheless, when a 47,000-strong British Expeditionary Force reached South Africa it suffered a series of reverses at the hands of the Boers. The British commander, Sir Redvers Buller, divided his army into three columns. One, under the command of Lord Methuen, was sent to relieve Kimberley, a second under General Gatacre being despatched to the north of Cape Colony, whilst Buller himself marched against the Boers that had invaded Natal. Methuen was repulsed at Magersfontein, Gatacre was beaten at Stormberg and Buller was defeated at Colenso. Buller renewed his offensive but his attacks at Spion Kop and Vaal Krantz were repulsed.

The defeats were a great embarrassment to Britain, and its response was to assemble an overwhelming force to crush the Boers. Britains top generals, Lord Roberts and Lord Kitchener, were placed in charge of what eventually amounted to over 200,000 regulars and 200,000 militia and irregulars. The full resources of the British Empire were employed with 16,000 volunteers coming from Australia, 6,500 from New Zealand, and others from Canada.

Even with this great deployment of force, the Boers defeated Kitchener at Paardeberg. But eventually the weight of numbers told. Kimberley and Lady-smith were relieved. The Boers at Paardeberg were surrounded and forced to surrender. The Transvaal and the Orange Free State were annexed to the British Crown.

This did not bring an end to the war, but it did alter the nature of the fighting. Unable to stand against the British in open battle, the Boers resorted to guerrilla warfare. They split up into small columns or Commandos of about 1,000 men which attacked detached British units or railways.

Kitchener responded by dividing up the country into sections with 3,700 miles of barbed-wire and 8,000 blockhouses. Having isolated each area in this way, the British troops systematically cleared each section of guerrillas. This prevented the fighting Boers from simply melting back into the farming communities only to re-emerge when the British troops had left their sector, the farms were burned and the women and children were herded into concentration camps. Gradually Kitcheners ruthless approach wore the Boers down and on 31 May 1902, the Boers accepted Britains peace terms.

* * *

The despatches collected in this volume cover the major engagements of the Second Boer War. The First Boer War has not been included. Due to restrictions of space it has not been possible to include all the casualty lists, though where it has been practical this has been done. Lists of individuals considered to be worthy of mentioning by their superior officers have also not been included in every instance for the same reason.

Unlike the despatches of Lord Raglan and his successors in the previous major war of the Victorian era, the Crimean War, the despatches of Redvers Buller, Roberts, Kitchener and their subordinates are highly detailed and comprehensive. This is perhaps most notable with regards to the Siege of Mafeking.

The place was considered to be of considerable strategic importance and Major General Baden-Powell undertook to personally conduct its defence. Mafeking withstood a siege of 217 days and its relief prompted unprecedented scenes of rejoicing across Britain. In his despatch, Baden-Powell provides not only an exciting narrative of the siege but he also details the number of soldiers and civilians in Mafeking, and their composition; the weapons available; the prices paid to native runners to deliver messages (which were high due to the likelihood of them being caught and killed!) and even the quantity of the rations doled out to the various military units.

There are also raw and dramatic accounts from the various officers which draw the reader instantly into the war. After the capture of Spion Kop, the British dug in and thought that their position was secure. Then as we read Lieutenant General Sir Charles Warrens report, a message is received from Colonel Crofton of the Royal Lancaster Regiment: Reinforce at once or all lost. General dead.