This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 2000 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

CAVALRY IN THE SHENANDOAH VALLEY CAMPAIGN OF 1862: EFFECTIVE, BUT INEFFICIENT

By

Major Michael Sullivan Lynch, USAF

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

ABSTRACT

This study is an analysis of Confederate cavalry operations in the Valley Campaign5 November 1861 through 10 June 1862. In a campaign dominated by the leadership of Major General Thomas Stonewall Jackson and his foot cavalry, what role did his mounted arm play in the campaign?

This study begins with a brief review of the historical evolution of American cavalry, explaining the differences between American and European cavalry. The study also includes background information on key issues of the campaign's cavalry leadership, organization, logistics, and tactics. The majority of the thesis discussion concerns the campaign's cavalry operations, including an evaluation of the cavalry's performance.

The conclusion of the thesis is that Jacksons cavalry arm significantly contributed to the Confederate success in the campaign. Cavalry contributions were strongest at the operational level of war. Despite their contributions, the cavalry was inefficient. Organizational turmoil, poor logistical support, high operations tempo, and limited training worked in concert to reduce efficiency. Although completed over one hundred years ago, the cavalry operations of Shenandoah Valley Campaign has some particular lessons-learned that still apply today. Among these are support for the soldier in the field, innovation and improvisation, combat leadership, leadership development, and training.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As with any endeavor, this thesis was completed through the assistance of many people. First, I wish to thank my thesis committee for their time, effort, and expertise. Their input was invaluable. Secondly, I wish to say a special thanks to Mrs. Nola Sleevi for her commitment of time, effort, and talent. With a solid background in history and an enthusiasm for the Civil War in particular, her knowledge and insight into the Shenandoah Valley Campaign were extremely valuable. Her willingness to help with this project was noble.

To all my family, including my parents, I can not express enough the importance of your support and encouragement. A special thanks is due to my wife, Shelli, my daughter, Sarah, and my son, Connor. Everyone sacrificed and each one contributed in his or her own unique way. No one better expressed the joy of seeing this project completed than my four-year old son did when, dancing and jumping up and down said, Daddy, youre done with your paper?

Finally, I wish to dedicate this work to my father, Thomas Joseph Lynch. Throughout the year, he provided constant encouragement. He was the first to recognize that this thesis was not a paper, but a book. Since the beginning of my life, my father has expressed the greatest degree of support for my endeavors. This project was no exception. In this year, my father battled against cancer in a positive and tireless manner, inspiring us all. As much as Turner Ashby is a hero to the South, so my father is to me.

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

If the Valley is lost, Virginia is lost. {1} Major General Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson, Stonewall in the Valley

Jackson shared this thought in a letter to Congressman Alexander R. Boteler on 3 March 1862. In this letter, Jackson explained both the serious threat facing the Confederates in the Shenandoah Valley and the need for additional soldiers to meet this challenge. Expressing an attitude that would characterize the campaign, Jackson anxiously anticipated an opportunity to eject Virginias invaders.

Preamble

Stonewall Jackson is already the subject of many military histories. In particular, Jacksons Shenandoah Valley Campaign has been a source of particular interest. Can one add anything more to the body of existing works on this subject? Jacksons infantry developed a reputation during the Valley Campaign for its mobility and earned the nickname of Jacksons foot cavalry. Considerably less written material about his Confederate cavalry forces in the Valley exists. {2} What were the accomplishments of Jacksons mounted cavalry? This area will be the focus of this thesis. In particular, this thesis will address one primary question: Did Confederate cavalry operations significantly contribute to the success of the Confederate 1862 Shenandoah Valley Campaign?

Before beginning, it is important to do some foundational work. An understanding of the Valley and its relative significance to both the North and the South is important. A brief overview of the broader context of the campaign is also necessary because it establishes the canvas upon which the Valley Campaign was painted. Additionally, it is equally important to consider, in terms of its purpose, both what this thesis is as well as what it is not. Finally, a firm foundation demands some indication of the relevance of the thesis to military operations of today and to those operations in the future.

Description of the Shenandoah Valley

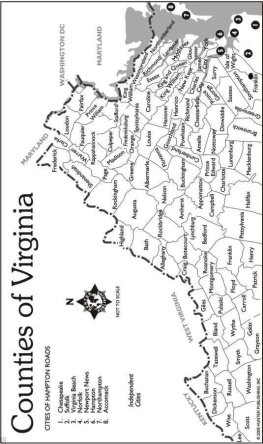

The Shenandoah Valley is a region that runs along the western edge of current day Virginia. (See Figure 1.) Flanking the Valley are two mountain rangesthe Blue Ridge in the east and the Alleghenies, of which the Shenandoah Mountains are a part, are in the west. Both of these mountain ranges run along a northeastern-southwestern axis. The Potomac River defines the northern boundary. From there, the Valley runs 150 miles southwest to the James River. There are three major rivers that flow in the Valleythe Shenandoah in the east, the Big Cacapon in the center, and the South Branch of the Potomac in the west. Each of these rivers flows northward into the Potomac. Consequently, the southern portion of the Valley constitutes the upper Valley and the northern portion constitutes the lower Valley. Because of the mountains that bound it, the Valley formed a natural boundary between the eastern and western theaters of the Civil War.

During the Civil War, the portion of the Valley between Staunton in the south and Harpers Ferry at the northeastern point was highly contested. In the lower Valley, thirty miles southwest of Harpers Ferry lies the town of Winchester. By one estimate, Winchester changed hands more than seventy times during the war. {3} The importance of the Valley began with the burning of the U.S. Armory in Harpers Ferry on 18 April 1861the day after Virginia seceded from the Union. The Shenandoah Valleys importance continued even after the final battle in the Valley, Cedar Creek, ended with Union occupation of Staunton on 3 March 1865. After this final Valley battle, Major General Phillip H. Sheridan began a destruction campaign in the Valley similar in scope to Shermans March to the Sea. David Martin described Sheridans destruction campaign in the following passage.