First Mariner Books edition 2016

Copyright 2015 by Nisid Hajari

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hajari, Nisid, author.

Midnights furies : the deadly legacy of Indias partition / Nisid Hajari.

pages ; cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-547-66921-2 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-547-66924-3 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-544-70549-5 (pbk.)

1. IndiaHistoryPartition, 1947. 2. India-Pakistan Conflict, 19471949. 3. PakistanHistory20th century. 4. Jinnah, Mahomed Ali, 18761948. 5. Nehru, Jawaharlal, 18891964. I. Title.

DS 480.842. H 35 2015

954.04'2dc23

2014034426

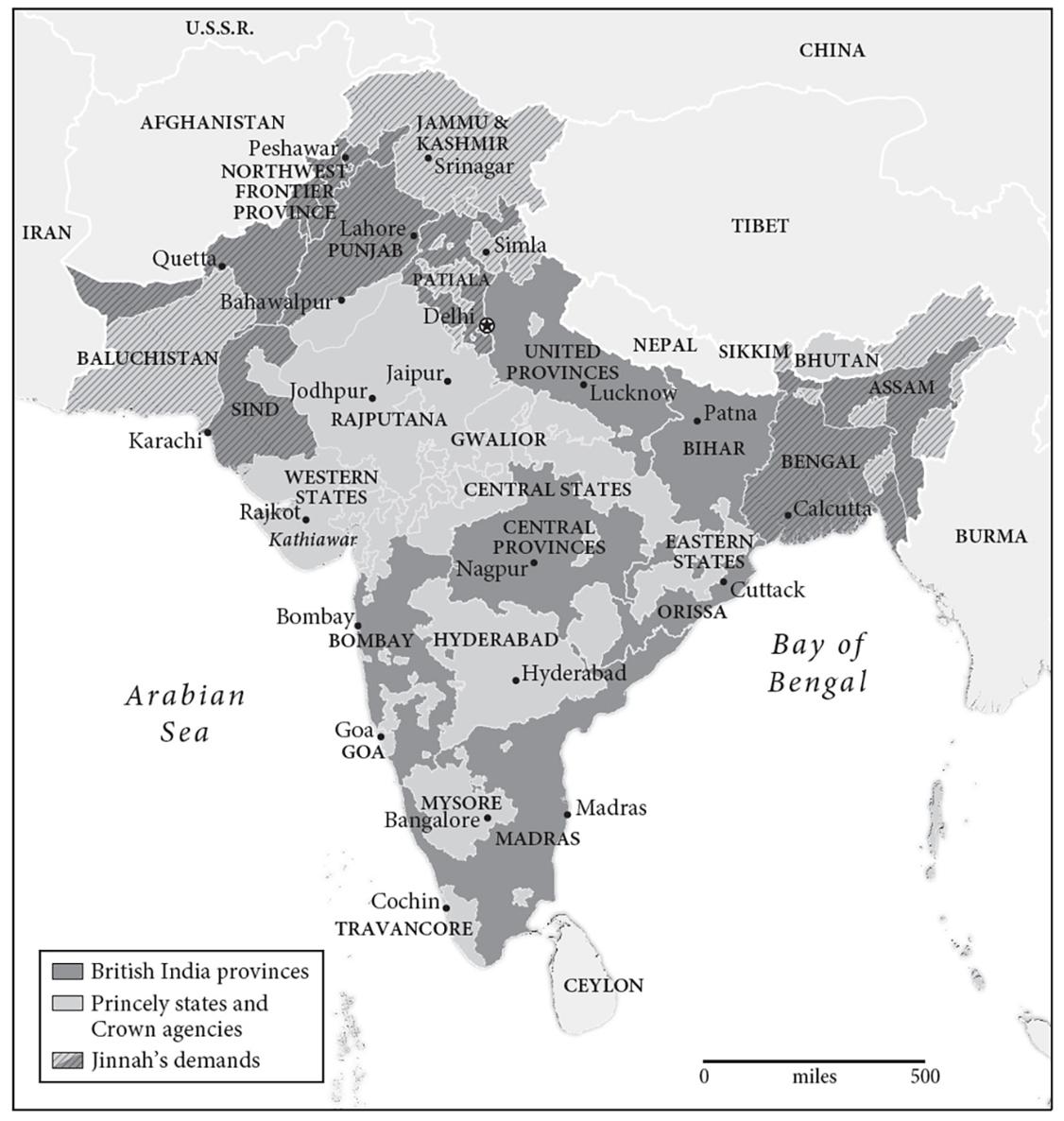

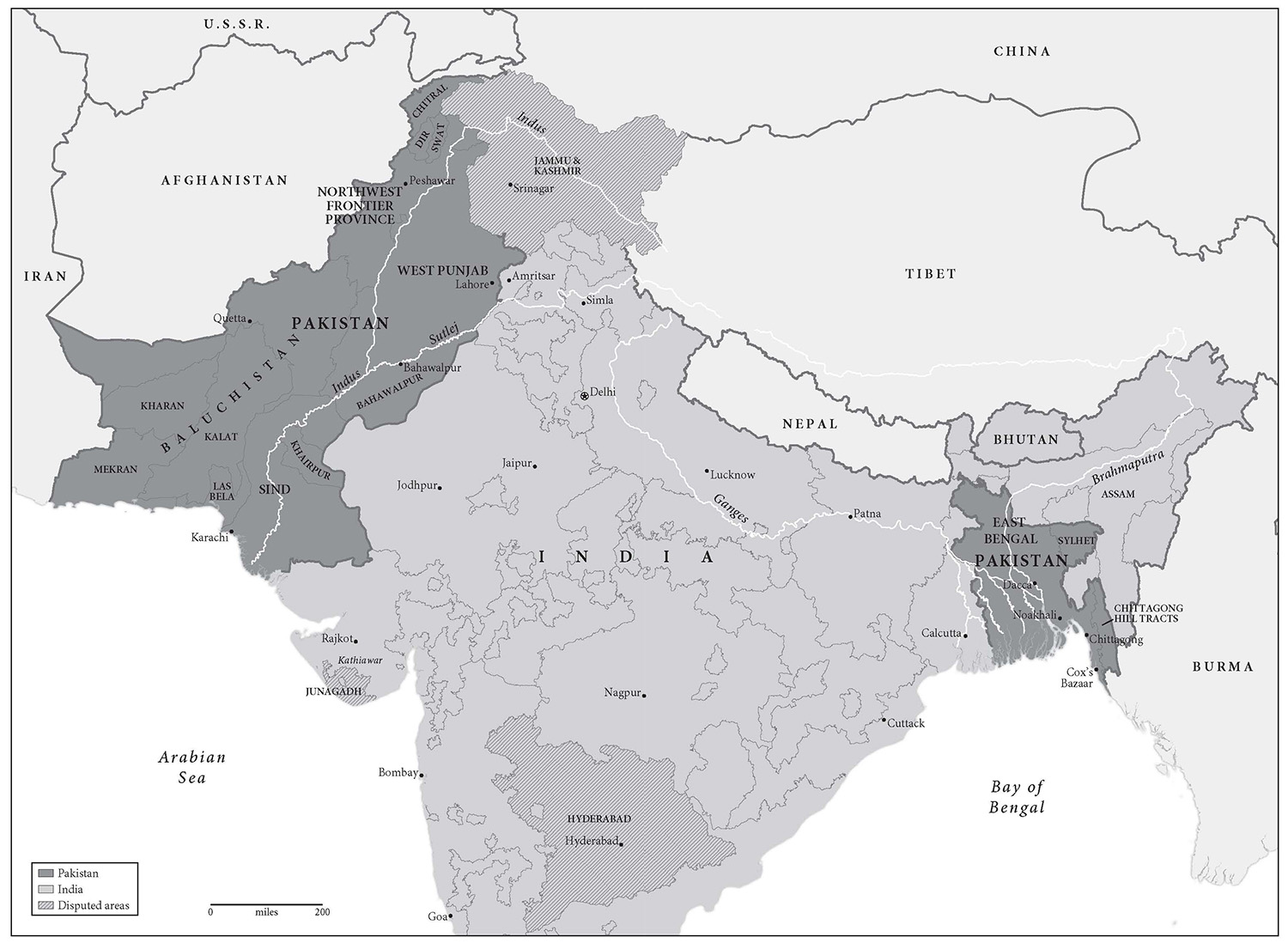

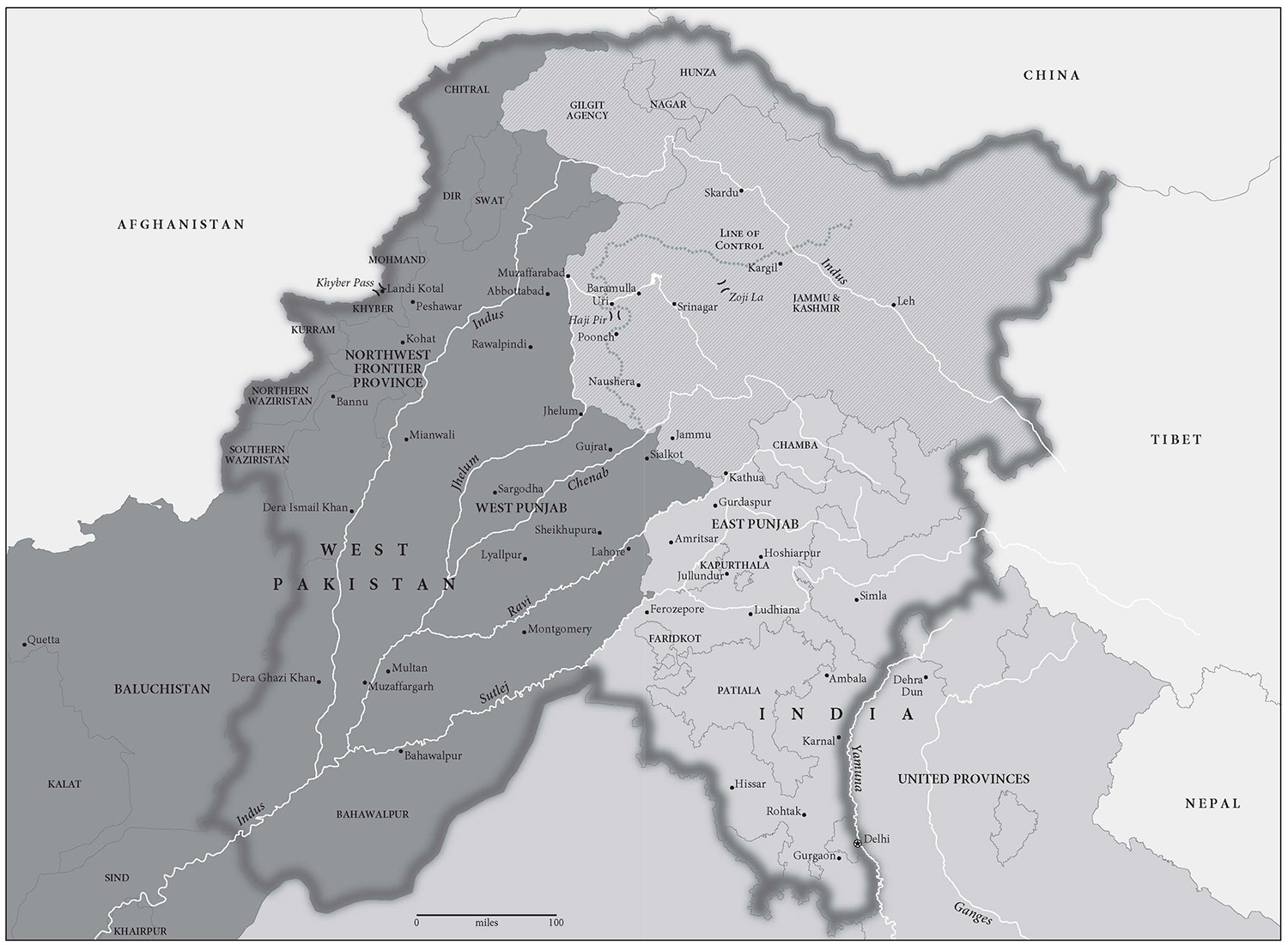

Maps by Glen Pawelski/Mapmaking Specialists, Ltd.

Cover design by Martha Kennedy

Cover photograph: Police disperse riots in Calcutta, 1946, Universal Images Group/SuperStock

v2.0616

PROLOGUE

A Train to Pakistan

A HEAD, THE JEEPS HEADLIGHTS picked out a lonely stretch of railroad track. The driver slowed, then, when still about a third of a mile away, pulled over and waited. All around wan stalks of wheat, shriveled by drought and rust, trembled in the hint of breeze. Two turbaned figures emerged from the gloom, borne by an ungainly, knock-kneed camel.

At a signal the five broad-shouldered men in the jeep piled out. They carried a strange assortment of objectsa brand-new Eveready car battery, rolls of wire, a pair of metal hooks with cables attached, and three lumpy, unidentifiable packages. Moving quickly, they joined the now-dismounted riders and headed for the copse of trees that lined both sides of the permanent way. When they reached an irrigation canal that ran along the tracks, several of the men slid down its banks and hid.

Two others dashed forward. Each tucked one of the mysterious parcels against a rail, then carefully attached a wire to the soft gelignite inside and trailed the cable back to where the others crouched. A third man brought the pair of hooks over to a nearby telephone pole and used them to tap into the phone line. As he listened, waiting for word of the Karachi-bound train, his compatriots grimly checked their revolvers.

The men were Sikhs, recognizable by their long beards and the turbans enclosing their coils of uncut hair. They had the bearing and burly physique of soldiersnot surprising given that their tiny community had long sent disproportionate numbers of young men to fight in the Indian Armys storied regiments. In the world war that had just ended two years earlier, Sikhs had made up more than 10 percent of the army even though they represented less than 2 percent of the population.

The eavesdropper motioned to his comrades: the train was coming. This was no regularly scheduled Lahore Express or Bombay Mail. Onboard every passenger was Muslim. The men, and some of the women, were clerks and officials who had been laboring in the British-run government of India in New Delhi. With them were their families and their ribbon-tied files; their photo albums, toys, china, and prayer rugs; the gold jewelry that represented much of their savings and the equally prized bottles of illicit whiskey many drank despite the strictures of their religion. On 9 August 1947 they were moving en masse to Karachi, 800 miles away, to take part in a great experiment. In six days the sweltering city on the shores of the Arabian Sea would become the capital of the worlds first modern Muslim nation and its fifth largest overallPakistan.

The country would be one of the strangest-looking on the postwar map of the world. One half would encompass the fierce northwestern marches of the Indian subcontinent, from the Khyber Pass down to the desert that fringed Karachi; the other half would include the swampy, typhoon-tossed Bengal delta in the far northeast. In between would lie nearly a thousand miles of independent India, which would, like Pakistan, win its freedom from the British Empire at the stroke of midnight on 15 August.

The Karachi-bound migrs were in a celebratory mood. As they pulled out of Delhi, cheers of Pakistan Zindabad! (Long live Pakistan!) had drowned out the trains whistle. Rather than laboring under a political order dominated by the Hindus who made up three-quarters of the subcontinents population, they would soon be masters of their own domain. Their new capital, Karachi, had been a sleepy backwater until the war; American GIs stationed there raced wonderingly past colorful camel caravans in their jeeps. Ministers perched on packing crates to work as they waited for their furniture to arrive. Their clerks used acacia thorns for lack of paper clips.

To the Sikhs leaning against the cool earth of the canal bank, this Pakistan seemed a curse. The new frontier would pass by less than 50 miles from this spot, running right down the center of the fertile Punjabthe subcontinents breadbasket and home to 5 million of Indias 6 million Sikhs. Nearly half of them would end up on the Muslim side of the line.

In theory, that should not have mattered. At birth India and Pakistan would have more in common with each otherpolitically, culturally, economically, and strategicallythan with any other nation on the planet. Pakistan sat astride the only land invasion routes into India. Their economies were bound in a thousand ways. Pakistans eastern wing controlled three-quarters of the worlds supply of jute, then still in wide use as a fiber; almost all of the jute-processing mills lay on the Indian side of the border. During famine times parts of India had turned hungrily to the surplus grain produced in what was now Pakistans western wing.

The Indian Army, which was to be divided up between the two countries, had trained and fought as one for a century. Top officersstill largely Britishrefused to look on one another as potential enemies. Just a few nights earlier both Hindu and Muslim soldiers had linked arms and drunkenly belted out the verses of Auld Lang Syne at a farewell party in Delhi, swearing undying brotherhood to one another. Cold War strategists imagined Indian and Pakistani battalions standing shoulder to shoulder to defend the subcontinent against Soviet invasion.

Many of the politicians in Delhi and Karachi, too, had once fought together against the British; they had social and family ties going back decades. They did not intend to militarize the border between them with pillboxes and rolls of barbed wire. They laughed at the suggestion that Punjabi farmers might one day need visas to cross from one end of the province to the other.

Pakistan would be a secular, not an Islamic, state, its founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, promised: Hindus and Sikhs would be free to prac The fight to establish Pakistan had been bitter but astoundingly shortoccupying less than ten of the nearly two hundred years of British suzerainty over India. Surely in another decade the wounds inflicted by the struggle would heal.