MIDNIGHTS DESCENDANTS

Copyright 2014 by John Keay

Published by Basic Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Designed by Pauline Brown

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by the Perseus Books Group

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Keay, John.

Midnights descendants : a history of South Asia since partition / John Keay.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-465-08072-4 (e-book) 1. South AsiaHistory. 2. South AsiaPolitics and government. 3. South AsiaRelations. 4. RegionalismSouth Asia. 5. GeopoliticsSouth Asia. 6. South AsiaSocial conditions. I. Title.

DS340.K37 2014

954.04dc23

2013045232

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In memory of Julia Keay

CONTENTS

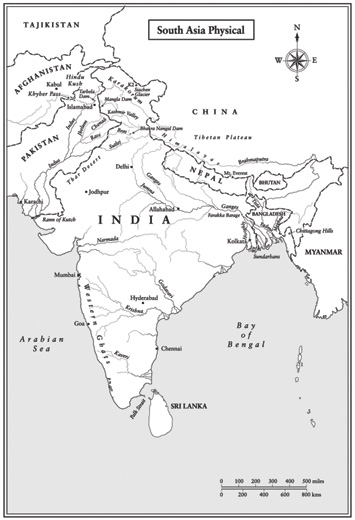

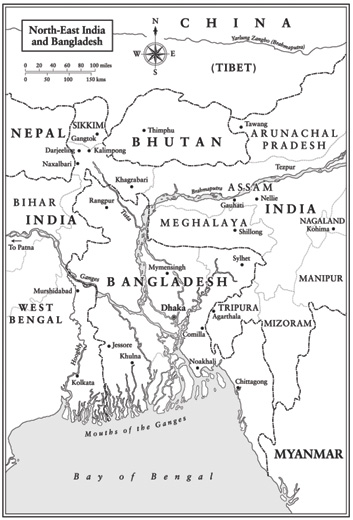

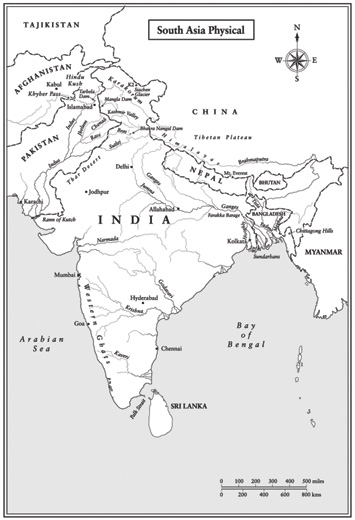

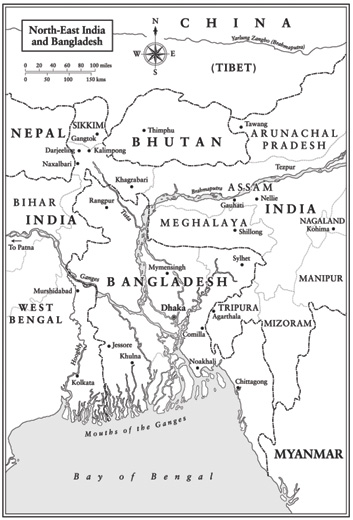

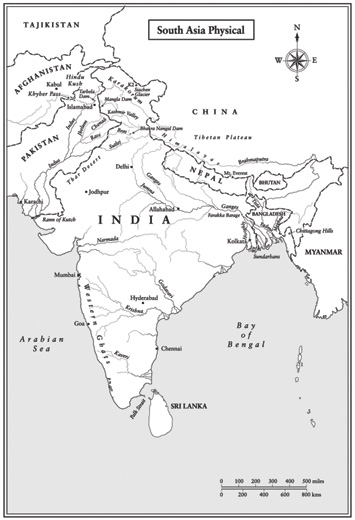

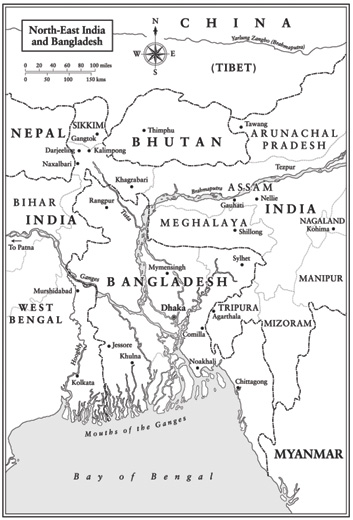

A PPROACHING BENGAL FROM OPPOSITE DIRECTIONS, the Ganges and the Brahmaputra rivers shy away from a head-on collision and veer south, their braided channels fraying and crisscrossing in a tangle of waterways that rob the parent rivers of their identities. Long before reaching the sea the Ganges has split into the Hooghly and the Pabna, among others, and the Brahmaputra into the Padma and the Meghna. Known as distributaries, these subrivers then fork some more, creating a maze of broad brown bayous whose combined seaward meanderings define the area known as the Sundarbans. Here, in the worlds largest estuarine wilderness, expanses of glossy mangrove and thick muddy water cover an area as big as Belgium. Islands are indistinguishable from mainland; promising channels expire in stagnant creeks. In the several designated wildlife sanctuaries, amphibious adaptation proves the key to survival. Crocodiles loll along the tide line, close-packed like sunbathers. Mudhoppers gawp and glisten in the slime, and the local tigers swim as readily as they prowl.

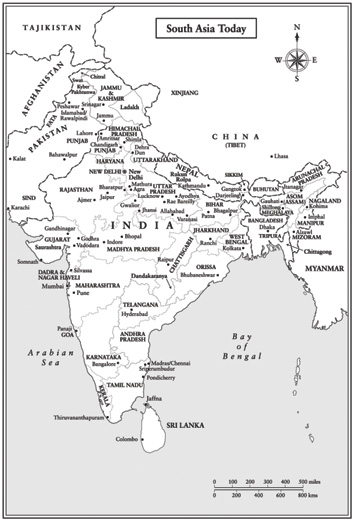

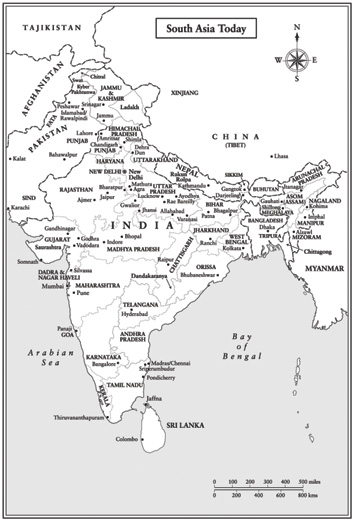

With roads a rarity, the best way to get around the Sundarbans is by boat, perhaps with a bike aboard for excursions on terra firma. A guide is essential, the trails being few and the landmarks fewer. The rivers tug one way, the incoming tide another. Neither is consistent: saltwater comes down on the ebb, freshwater is backed up by the flow. The logic of the currents is as hard to fathom as that of the international border that here separates India and Bangladesh. Maps show the border as a confident line bisecting islands and slicing through peninsulas as it ricochets from side to side down the broad Raimangal waterway. Its trajectory provides the region with its one feature of human geography. But on the groundwhere there is groundthe border is scarcely to be seen. Shifting mud banks and encroaching mangroves are no more conducive to frontier formalities than they are to cartographic precision. Apportioning the Sundarbans between India and what was then part of Pakistan must have been like trying to carve the gravy.

A game warden announces a sighting: Changeable hawk-eagle. He points to a large raptor lodged in a dead tree. Its a darker version of the one in peninsular India.

The bird is rooted to its perch and motionless. It could be stuffed, its taloned feet nailed to the branch, except that every now and then it moves its head ever so slightly, as if troubled by indecision. Choosing the behavior appropriate to its species is problematic for a changeable hawk-eagle. Should it quarter low over Indias chunk of the Sundarbans or soar high above Bangladeshs? Is this a hawk day or an eagle day? Or just another changeable day? The options make for great uncertainty.

So is that bit over there India or Bangladesh? I ask. Nothing seems one thing or another in this gooey wilderness.

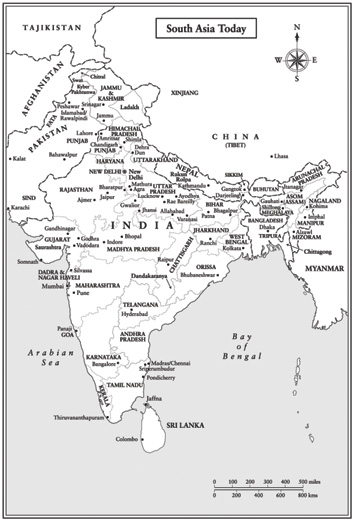

Oh, thats India. Bangladesh is over there. See? But it should be India. Khulna, that whole district, should have come to India at Partition. It had a Hindu majority.

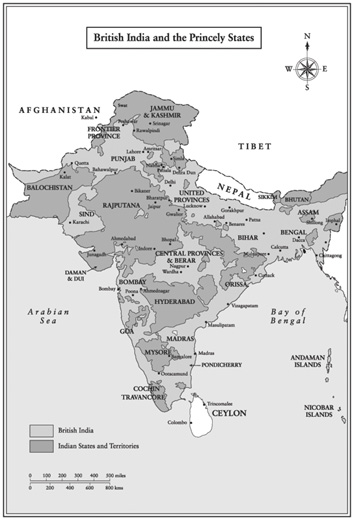

Khulna was not awarded to India because Murshidabad, a Muslim district to the north of Calcutta that straddles the Hooghly River, was preferred by Delhi on the grounds of strategic contiguity and economic convenience. Eastern Pakistan, as Bangladesh then was called, got Khulna by way of exchange. Hence mainly Muslim Murshidabad went to mainly Hindu India, and mainly Hindu Khulna went to mainly Muslim Pakistan. So much for the fundamental principle on which British India was divided by 1947s Great Partitionthat contiguous areas where Indian Muslims were in a majority were to constitute Pakistan and areas where they were not in a majority were to constitute the new India.

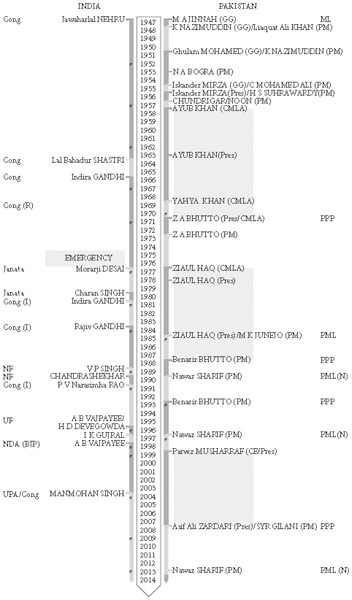

Dividing the subcontinent had itself been a compromise and proved a heavy price to pay for independence. Flying in the face of fifty years struggle for a single India and of a shared cultural and historical awareness that stretched back centuries, it had been dictated by three recent developments: Most Indian Muslims had come around to the idea of a Muslim homeland of their own, most Indian nationalists were insisting on a successor state that was strong enough to resist such demands, and the British were desperate for a fast-track exit. Adopted only as a last-minute expedient, Partition was widely regretted at the time. And it has been rued ever since by all who hold life, livelihood, and peace to be dear.

Next page