Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2019 by Josh Foreman and Ryan Starrett

All rights reserved

First published 2019

E-Book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.721.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019936358

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.321.9

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all those historians, researchers, archivists, teachers, artists and photographers who came before us and paved the way for a project like this. We thank them for allowing us to stand on their shoulders and see the history of the Mississippi Sound through their own work.

We would like to extend a special thanks to those directly involved in our projectJoe Gartrell, acquisitions editor at The History Press; the Mississippi Department of Archives and History; Barbara Webb, who generously shared her stories and postcard collection; newspapers.com for creating such an amazing research tool; the archives at Spring Hill College; Richard Starrett for the editing; the Bay St. LouisHancock County Library; the Hancock County Historical Society; the Library of Congress, Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, Yale University and Internet Archive for digitizing and sharing valuable documents and artwork from the past; Joyce Gubbins and Jill Woodliff for recording and sharing the incredible story of the Robbins family; and Wes Foreman for help with research.

CONTACT CRISIS

Europe Comes to the Mississippians

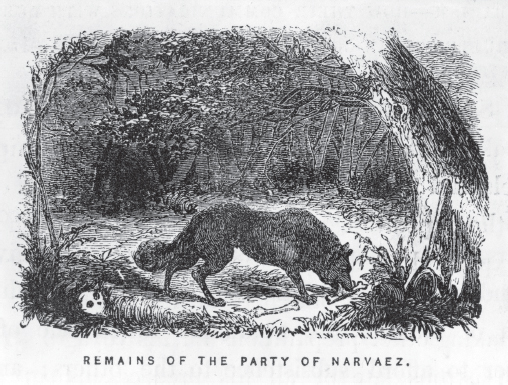

It was an angel of deliverance or a grim specter: a canoe trailing the Narvez party as it entered the Mississippi Sound in the fall of 1528. The canoe wouldnt come close enough for the men aboard the five rafts to see who was in it. It just waited, watched, then left.

The 240-odd men were close to death, having survived half a year of exploring a Florida that seemed to fight them like a body fighting an infection. Fifty or so of their party hadnt made it. Theyd had enough of Florida. For the past month, theyd been floating on crude rafts in the Gulf of Mexico, hoping to make their way west to the Rio Grande. They had run out of food and water, and they expected to die.

Soon after the ghostly canoe shadowed the men, they made landfall at a small island, perhaps Petit Bois or Horn, two barrier islands surrounding the sound. They searched for fresh water but found none. A storm hit, and the men hunkered down for six days. They grew so thirsty that some drank seawater. Men began to die.

They thought of the canoe. With nothing to lose, they set out in the direction theyd last seen it traveling, not knowing whether theyd find land or their deaths. They sailed for about ten miles. Then they spotted itan Indian village on the shore. They realized God had rescued them in the hour of greatest distress. Would this be a quick and violent end to their suffering, or salvation? The Indians saw them and met them at sea with canoes. The Indians guided them back to their village, where the men saw something more precious than gold: jars of fresh water and plenty of cooked fish.

The menmostly Spaniards with some other Europeans and Africans mixed inhad made landfall on the Gulf Coast somewhere between Pascagoula and Mobile. The Indians who greeted them there were most likely members of the Pensacola people, a subgroup of the Mississippian Culture that had spread across the South and Midwest at the time of first European contact. Their meeting represents the first recorded time Indians had met Europeans along the shores of the Mississippi Sound.

Among the Spanish that day was a man named Alvar Nez Cabeza de Vaca. It is because of him that we know such vivid details of the expeditions experiences on the Gulf Coast. Cabeza de Vaca had been the treasurer for the voyage, which had become more a fight for survival than an expedition. As more and more of his Spanish compatriots died off in the New World, he survivedfor eight years. After living in the New World among natives for those years and crossing the North American continent on foot, he finally made it back to Spanish-controlled Mexico and wrote down his tale.

Remains of the Party of Narvaez, by John William Orr, 1858. Library of Congress.

The Spanish expedition was being led that day at the sound by a man named Pnfilo de Narvez, tall and blonde-bearded with a reputation for rashness, ego and indifference to the suffering of others. Those who knew him described a man who would sit on a horse, statuesque, and watch a group of Indians being massacred, who sought to keep all spoils of conquest for himself, and who kept a violent rivalry with fellow conquistador Hernn Corts. It was Narvez who had first decided to leave the safety of his ships and head inland into Florida near Tampa Bay.

On shore with the Indians, Cabeza de Vaca and his compatriots partook of the fresh water and fish that the Pensacolas provided. The Pensacolas were tall and well built and didnt carry bows or arrowsa relief to Narvez and his men for sure. Theyd been harried by native archers as they made their way through Florida. Some of the Spaniards who were particularly ill lay on the beach. Others, including Narvez and Cabeza de Vaca, walked with the chief of the local Pensacolas to his hut.

Inside the hut, the Spaniards feasted on fish. They gave a bit of the maize theyd saved to the chief, who wore a fine robe of marten-ermine skin that gave off a strong odor of amber and musk. Everything seemed to be going OKand then the sun set.

Shortly after sunset, the Pensacolas attacked Narvez and his men, storming into the hut where the chief and the Spanish leaders sat. The Spanish tried to hold the chief as a shield against attack, but he slipped away, leaving them gripping his fine robe. Narvez was seriously wounded by a stone to the face. The Spanish rushed back to their rafts, leaving behind a defense force of fifty men to fight against the Pensacolas through the night. Cabeza de Vaca was thankful they didnt have many bows and arrowsotherwise the attack might have been much deadlier.