Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

THE SIEGE OF ST. AUGUSTINE IN 1702

By

Charles W. Arnade

Table of Contents

Contents

Table of Contents

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

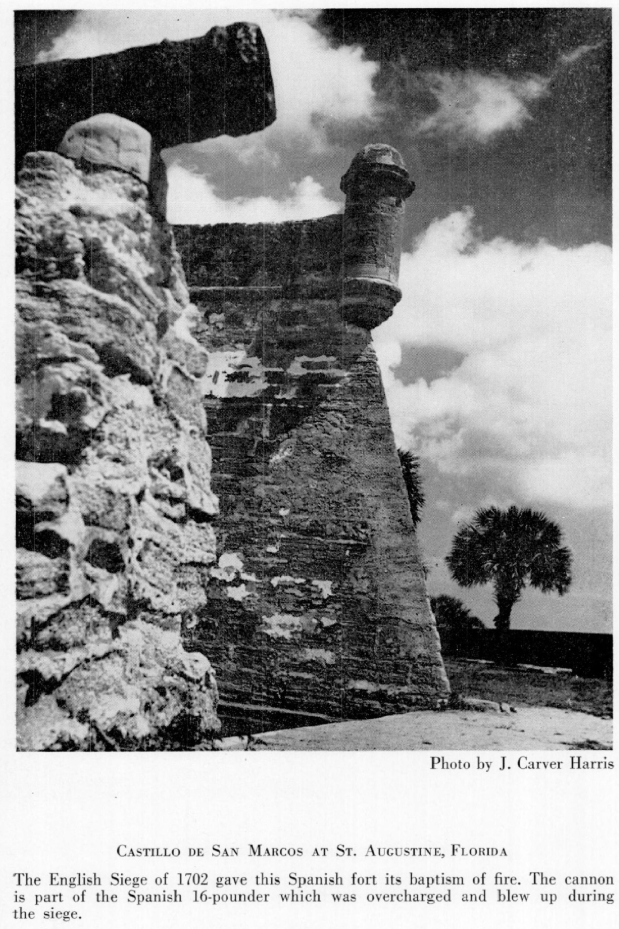

Research for this monograph was made possible by a generous grant from the St. Augustine Historical Society. The grant enabled me to dedicate a full two months in the summer of 1958 to research and writing. Mr. J. Carver Harris, Mrs. Doris Wiles, Mr. J. T. Van Campen, Mr. X. L. Pellicer, Mrs. Max Kettner, Mrs. Luis Arana, and Mr. William Griffen of the Society were helpful at various times. Mr. Albert Manucy, Mr. Luis Arana, and Mr. Ray Vinten of the United States National Park Service (which today administers Castillo de San Marcos National Monument, the historic fort that is so much a part of this narrative) gave valuable technical and scholarly help. Professors Hale Smith, Charles Fairbanks, Benjamin Rogers of Florida State University, and Donald Worcester, Lyle McAlister, Rembert Patrick, John Mahon, Curtis Wilgus, John Goggin, and Ripley Bullen of the University of Florida offered valuable advice. A special word of thanks goes to Mr. Julien . Yonge and Miss Margaret Chapman of the P. K. Yonge Library of Florida History for their help and for making many facilities available to me. Dr. Mark Boyd of Tallahassee, Mr. David True of Miami, and Mr. Edward Lawson of St. Augustine at one time or another were extremely helpful. My wife, Marjorie, as usual had the tedious chore of typing the various drafts. To these friends, and especially to the St. Augustine Historical Society, many thanks. Naturally I assume full responsibility for the content of the monograph.

CHARLES W. ARNADE

GAINESVILLE, FLORIDA

SEPTEMBER, 1959

ILLUSTRATIONS

Castillo de San Marcos

English Advance on St. Augustine

St. Augustine and Western Florida, 1702

English Advance and Retreat Routes

Spanish Map of St. Johns River Area

The Attack Time Table

Plan of the Fort

Seventeenth Century Warfare

Spanish Defense Zone in St. Augustine

Diagram of the Siege

Plan of Port and Fort of St. Augustine

The British Withdrawal

1. FLORIDA AND CAROLINA AROUND 1700

In 1670 a new English colony had come into existence on the North American continent. Its first colonists came from England and Barbados and called their new home Carolina. They established their towns and plantations in territory claimed exclusively by Spain as part of Florida. Although Spanish hegemony in the Carolina land was hardly perceivable since the Spanish frontier had been withdrawn to the south, the very soil on which the first Carolinians stepped was historical ground where once the Spanish banner proudly flew. The famous Pedro Menndez de Avils had personally established forts and outposts in Carolina a century before the English arrival. Overextension, lack of gold and precious metals, apathy, ferocious Indians, maladministration, jealousies, and other causes forced the Spanish to retreat toward St. Augustine and Apalachee. Carolina and north Georgia as well as Alabama remained Spanish only in name and on paper.

The settlers of Carolina, imbued by a restless energy, a religious fervor, a shrewd business instinct, and a hatred for Catholic Spain, were determined to remain and expand. This they did. In all directions, but especially west and south, the pioneers and traders of Carolina blazed the trail. The forceful story of this chapter of American colonial history has been written with scholarly pen by Professor Verner Crane in his study The Southern Frontier () {1} , today a classic of American history. The men of Carolina, according to the Spaniards, were living, moving, and expanding on Spanish soil. Surely a controversy, if not war, was in the making over the debatable land, a phrase employed by Professor Herbert Bolton (6).

For more than thirty years an undeclared war was waged in this disputed land with Guale, or eastern Georgia, as the main battleground. Spains efforts to eradicate English Carolina from St. Augustine were complete failures. Many natives flocked to the English side, the side which had more goods to offer. Those Indians who remained loyal to Spain were eagerly considered slave material by the Carolina plantation owners. Therefore raiding parties by the English and their Indian allies forced the Spaniards to fall back farther south. One Spanish governor after another requested help to destroy the English menace, but nothing was forthcoming. One positive action was undertaken, however, when St. Augustine was made a main bastion for Spanish defense of the Atlantic. A massive stone fort, the dream of every governor since Menndez de Avils, became a reality. It was started in 1672, and by the end of the century the fort at St. Augustine was the strongest and largest on the continent this side of Veracruz (). The stage was set for a larger English-Spanish engagement. International events slowly led to its fulfillment.

Frances ownership of the best waterways of North America was yet incomplete without sovereignty over the Mississippi, especially its mouth. By the end of the seventeenth century, just when Carolina was expanding, France decided to act since Spain had neglected the Gulf coast. By 1700 France had achieved her purpose and Louisiana was in the making. The Spanish crown, wishing to forestall the French, occupied Pensacola Bay and in this way a new area of conflict was created. Furthermore, while Carolinians gained at the expense of Spain in east Georgia, their more enterprising traders were moving west, approaching the Mississippi. Another regional clash was shaping up. The outlook was for a triangular struggle over the Southeast.

To the Carolinians the main enemy had been Spain ever since the creation of their province. This was most natural as they had intruded on soil claimed by Spain, and they were living in the very chaps of the Spaniard (, p. 3, n. 1). At the same time they were disdainful of the Spaniards, sure that Spains forced exit from North America was just a matter of time. The Carolinians underestimated the strength and might of Spain; they had a more healthy respect for the French. France was the mightiest nation in Europe with a great colony in North America. Although removed from the battlefield of King Williams War (1689-1697), Carolina knew that England had failed to eject France from Canada. Both countries had fought to a stalemate in America. In Carolina Frances power was overestimated. The news of the establishment of Louisiana meant that Carolina traders going west would meet with Frenchmen moving north and east, and this was considered a serious matter. The Spanish danger was relegated to a secondary position. The struggle for the Mississippi, in which Carolina would play a vital role, surged to the forefront. But a sudden new international development in Europe brought about a shift in the triangular picture of the North American Southeast.