Pagebreaks of the print version

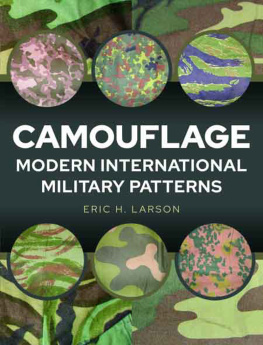

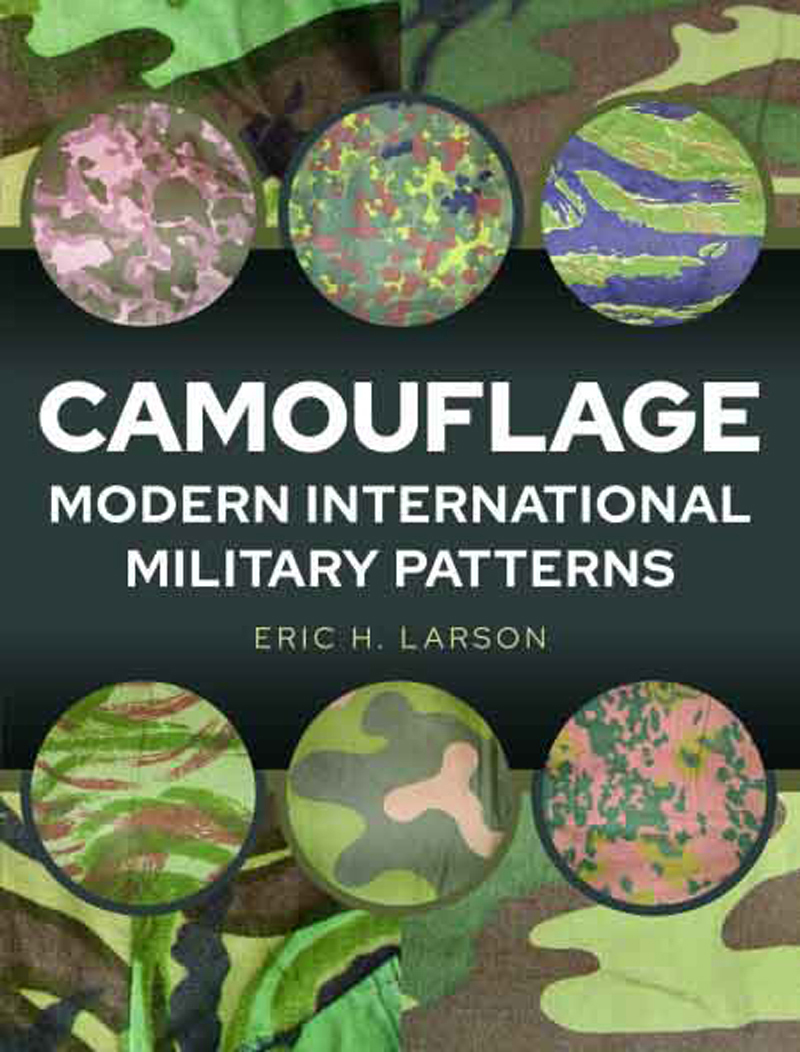

Camouflage

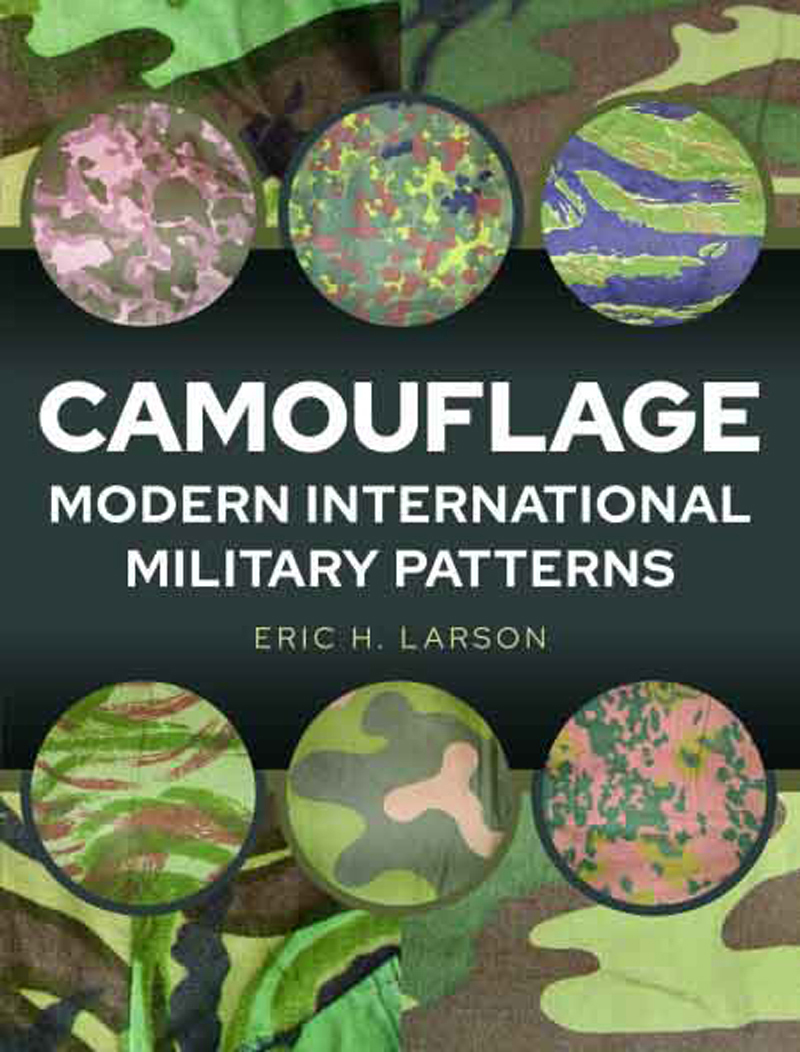

Camouflage

Modern International Military Patterns

Eric H Larson

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Eric H Larson 2021

ISBN 978 1 52673 857 8

eISBN 978 1 52673 858 5

The right of Eric H Larson to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Acknowledgements

This book is a culmination of thirty-five years of research and continuous exposure to military personnel and culture. Although it is a product of my own creation, I would be remiss if I took all the credit for the research and information provided in this volume. Much of the historical information can be credited to the generation or two of professionals and hobbyists that came before mine, as well as to historians that had the foresight to keep good records on a subject that is quite often overlooked.

Those of us who developed an interest in military camouflage more than twenty years ago owe a huge debt of gratitude to Dr Jean-Francois Borsarello, one of the pioneering researchers on this subject and the publisher of some of the first reference materials in English on camouflage uniforms. Likewise, I believe we are equally indebted to the multitude of military photographers and combat photojournalists out there who are largely responsible for recording many of the images that analysts such as myself have relied upon as primary source material for our research. Of these individuals, I would single out Yves Debay as the single most influential and critical recorder of military conflicts in the latter part of the twentieth century, whose dedication to combat photojournalism ultimately cost him his life in 2013.

My personal gratitude extends to a lot of other individuals. Some of these folks have generously assisted me personally by sharing their own research or helping to collect data and locate source material, while others can still be thanked for their indirect contributions to the fields of camouflage studies and the history of military conflict in the post-war world. While I have made every effort to include as many people that I feel have made a significant contribution to this book in the list that follows, there are a select group of people that must remain anonymous and whose names will not be mentioned here. These folks know who they are, and I hope they also know how valuable I consider their contributions to my work, and to the greater field of knowledge that is camouflage studies.

Herewith follows a list of people that have helped, directly or indirectly, make this book possible. My thanks go out to each and every one of you.

Beni Antares (Indonesia)

Andreas Arphan (Malaysia)

Filippo Buccaro (Italy)

Mark Campbell (Canada)

Henrik Clausen (Denmark)

Kenneth Conboy (USA-Indonesia)

Dion Desembriarto (Indonesia)

Dennis Desmond (USA)

Peter Erickson (USA)

Marco Garofalo (Italy)

Gilles Gorgues (France)

Jim Hooper (USA)

Dominic Hyde (United Kingdom)

Alex Iide (Brazil)

Richard D. Johnson (USA)

Carlos Caballero Jurado (Spain)

Leo Karlin (USA)

Samuel Katz (Israel)

Marko Kocoljevac (Serbia)

Michal Konek (Czech Republic)

John Laffin (United Kingdom)

Thomas Lundberg (USA)

Salvatore Mascoli (Italy-USA)

D. Matz (Brazil-USA)

Santiago Medina (Spain)

Juan Morales (Spain)

Eric Micheletti (France)

Piet Nortje (South Africa)

Werner Palinckx (Belgium)

Jorge Panuncio (Uruguay)

Daniel Peterson (USA)

Ben Playford (Australia)

Riaan Rossouw (South Africa)

Maksim Savochkin (Uzbekistan)

Amin Allah Shakeri (Iran)

Shelby Stanton (USA)

Peter Stiff (United Kingdom)

Gani Sunglao (Philippines)

Juan Pablo Tessiere (Argentina)

Philip Thum (Austria)

Andress Vargas (Mexico)

Al Venter (South Africa)

Steven Wende (South Africa-USA)

Martin Windrow (United Kingdom)

Introduction

What is Camouflage?

A typical definition of the term camouflage might render a way of hiding soldiers and military equipment, using paint, leaves, or nets, so that they look like part of their surroundings. In terms that apply specifically to military personnel, we typically think of camouflage as articles of clothing printed in designs that, under the correct conditions, will render the wearer invisible to a casual observer.

Historically, this would have been a perfectly acceptable way to think of military camouflage, given the fact that its purpose from inception was to disguise or conceal the wearer. It may seem perplexing to the reader, then, to discover that we must really arrive at a much broader definition of the word, if we are to delve more deeply into the variety of designs and color combinations that comprise military camouflage in the second half of the twentieth century and to the present day.

Up to the late 1970s, it would be accurate to say that camouflage designs were almost exclusively of a pragmatic nature. That is, the developers intended for the wearer to be disguised or hidden when wearing or employing it. However, at some point in the 1980s, national laboratories, private companies, and individual camoufleurs began playing around with the color schemes of typical camouflage patterns, so that the wearer ended up standing out rather than becoming more obscure. The earliest of these non-functional patterns were the so-called urban camouflage designs (usually employing shades of grey and blue in combination with black). While it might be argued that these initially had a functional purpose in mind, in practice the brighter blues and lighter greys tended to distinguish rather than disguise the wearer, becoming more a mark of pride instead of a functioning operational garment. In the latter part of the twentieth century, blue and grey camouflage became a mark of distinction for many law enforcement agencies throughout the world.

Straying even further from the practical aspects of camouflage design, by the late 1990s we see numerous distinctive patterns emerging whose sole purpose is to immediately identify the wearer either as coming from a particular unit or entity, or at least stand out and be easily identified whether in a crowd of people, or in extreme situations such as search and rescue missions or firefighting. Purists will insist that true camouflage must be functional and, as a linguist, I am prone to agree with them, up to a point. Yet, we cannot deny the fact that colorful (or even garish) designs that utilize traditional shapes, drawings, and geometrical patterns have some relationship with the more functional, traditional camouflage designed for the typical infantry soldier. There is a relationship, and if you were to query the average collector of camouflage uniforms from any part of the world, I am sure they would admit they have included at least some examples of non-functional camouflage patterns in their collections.