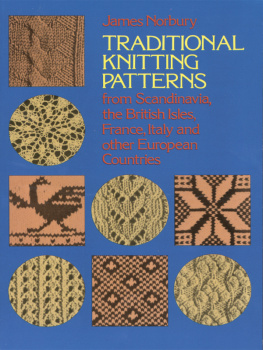

Traditional Knitting PatternsTraditional

Knitting Patternsfrom

Scandinavia, the British Isles, France,

Italy and other European Countries JAMES NORBURY DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC

NEW YORKCopyright Copyright 1973 by Dover Publications, Inc. Copyright 1962 by James Norbury. All rights reserved. Bibliographical Note This Dover edition, first published in 1973, is an unabridged republication of the work first published in 1962 under the title Traditional Knitting Patterns. This edition is published through special arrangement with B.T. Batsford, Ltd., 4 Fitzhardinge Street, London, the original publishers. International Standard Book Number

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-21013-1

ISBN-10: 0-486-21013-8 Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

21013815

www.doverpublications.com For Betty Morgan and Ronald SetterMy friends, we will not go again or ape an ancient rage,Or stretch the folly of our youth to be the shame of age,But walk with clearer eyes and ears this path that wandereth,And see undrugged in evening light the decent inn of death;For there is good news yet to hear and fine things to be seen,Before we go to Paradise by way of Kensal Green. G. K. K.

Chesterton Contents ART IS SKILL in making things that are useful. In this simple dictum my friend the late Eric Gill, sounded the death-knell on the cranks and phonies who spell fine art in capital letters and common or garden craftsmanship in small ones. Some months later he enlarged upon the theme by stating categorically that, the artist is not a special kind of man but every man is a special kind of artist. Many people still think that the sanity of Gills phrases led to the acceptance of parallels that cannot be justified in the realm of common sense. What he virtually does is equate the work of Michelangelo with the day-to-day job of the ordinary bricklayer. Surely, since Michelangelo himself was content to be called a workman, there is some justification in this suggestion.

A brick properly laid is as significant as a painting, a carving or a piece of sculpture. The tragedy of our age is that we have divorced things from the places where they were meant to be, and shut them up in art galleries where at times the most beautiful objects tend to look like eccentric monstrosities because they have been divorced from their proper setting. Once we accept the full implications of Gills definitions, we see that the splendour of the Taj Mahal; the elegance of a Chippendale chair or a Sheraton writing-desk; the perfect shape of a Wedgwood teapot; or the fashion lines of a well-designed knitted sweater, all form an intrinsic part of the creative pattern of being called into existence by man the craftsman. They are a tribute to otherness, to that sense of timeless wonder that is mans true habitation. The principles of design are basic. They cannot be classified into any specific category.

The great builders of the past, those architects whose genius created the temples of Greece, the palaces of Rome, the stately homes of Florence, all called on the craftsman in gold and silver, in metal and stone, in silk and wool, to add to their basic creation those refinements that made it a thing of immortal splendour. What are these principles? They are the simple shapes of the circle, the square, the cross and the waved line that are fundamental to all forms of design. Rooted as they are in mans thirst for divine things, they represent his finite being seeking to know and understand the meaning of infinity. The circle, the serpent swallowing its own tail, a line that has neither beginning nor end, is the oldest symbol of eternity. The square, the formal lines of the habitation that became the home is an attempt to capture the sense of infinity in finite terms. The cross, with its four arms extending endlessly into space is the mark of the adventurous spirit that is always seeking to move from the known to the unknown, from death to life, from mortal imprisonment into that world of a being which satisfied the immortal longings within him.

The waved line, the ever-recurring upsurge of the water of life that nourishes the seeds out of which the whole of creation has emerged. This concept of design is an integral part of the true philosophy of living and doing and being. It is rooted in the primitive mystery and magic that surrounded man in the dawn time of life on this planet. These symbols were used to decorate the robes of the witch-doctors, and the vestments of the ancient priest. They mark them as being a race apart, human beings dedicated to the service of the gods and seeking to bring about the reconciliation between the known and the unknown. Later the same symbols were used to decorate the home, to remind man that this was his temporary habitation.

Beyond the shadow of the walls of the cave he inhabited was a world surging with life and dominated by the haunting sense of the unknown. The first fabrics that man produced were simple cloths made from undyed fibres out of which he created clothes for himself and hangings for his home. At a much later stage in the development of the craft of weaving, man painted simple patterns on these cloths and later still learnt how to weave the patterns into the fabric itself. Knitted fabrics are an integral part of the development of textiles to be used in the service of man. It is not surprising, therefore, that we find in traditional knitting patterns a repetition of the principles of design that has already become part of the woven textile story. With the rise and fall of ancient cultures designs became more complex, colours more varied and although the symbolic meaning of the patterns themselves have been lost in the mists of antiquity, the patterns still remain as part of our universal heritage.

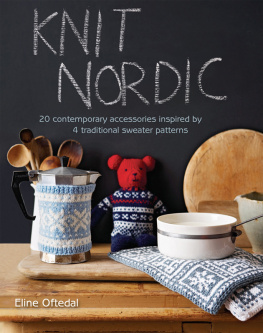

It is interesting that in the textiles of ancient Peru; the knitted tent flaps of the early Nomads of North Africa; the magnificent knitted carpets of the Renaissance; the wonderful draperies and bedspreads made by the Dutch people in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; the exquisite knitted lace of France, Vienna and Shetland; the gaily decorated peasant coats of the Austrian Tyrol; the highly sophisticated sweaters of Fair Isle; all embody within themselves a common tradition. Each little pocket of craftsmen gave their own particular twist to our story. The knitters of the Austrian Tyrol sprinkled their heavily embossed fabric with brightly coloured embroidered flowers reflecting the beauty of late spring in the Austrian valleys. The knitters of Fair Isle, inheriting their designs from Spanish sources, still preserve the Catholic tradition that made Christendom. We can still find on the sweaters they knit The Sacred Heart, The Rose of Sharon, The Star of Hope and The Crown of Glory. When we move to the ice-cold wastes of Norway, we find that the fir tree and the reindeer have been copied in their woven and knitted fabrics and that even peasant costumes have been transformed into dancing figures that form border patternings on their gay sweaters.

The fishermen and sailors, who were great knitters in their day, have taken the ropes and the anchors and have translated these into cable patterns and embossed designs, thus allying their day-to-day life as they go down to the sea in ships with the craft they practised in knitting jerseys to protect them from the elements. In this book of Traditional Knitting Patterns, I have collected together a selection of the basic fabrics that I have found in all those parts of the world I have visited where the knitters craft is an essential part of the life of the common people. It is surprising how the fabrics themselves reflect in some ways the temperament of their creators. The Mediterranean countries have given us gaily coloured designs that have within them something of the laughter and sunshine that makes for the gaiety of the life of the common people. Germany and Austria present a more sombre mood, a heavier, more prosaic approach in texturing and patterning. In Holland we find a puritan simplicity and an almost stark and severe approach that reflects the sturdy and simple life of these good-hearted people.

Next page