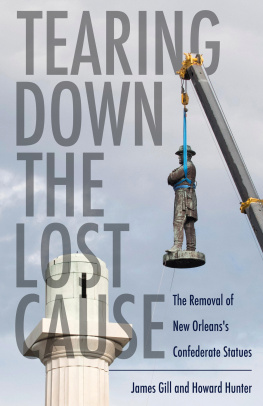

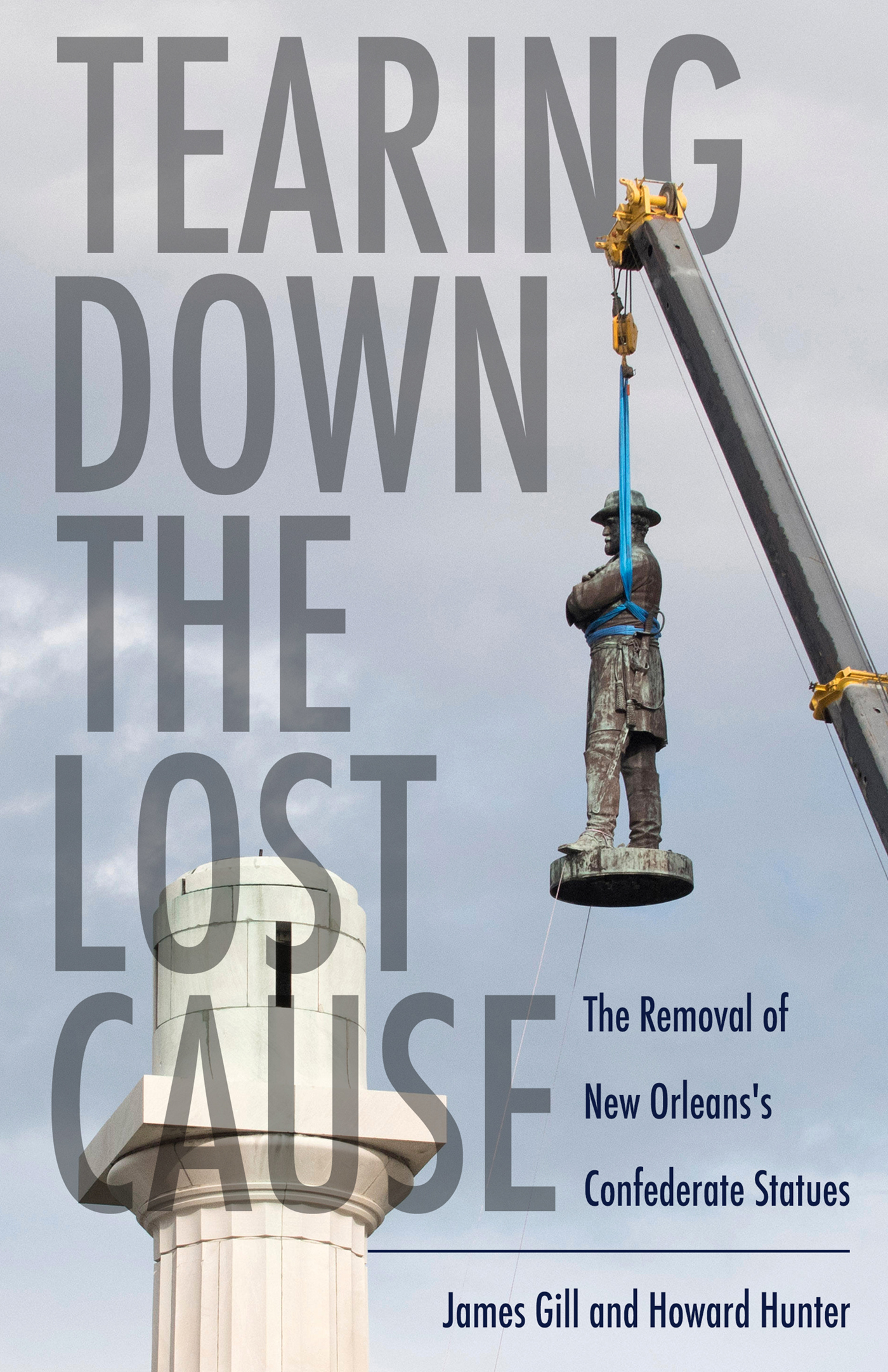

TEARING DOWN THE LOST CAUSE

TEARING DOWN THE LOST CAUSE

The Removal of New Orleanss Confederate Statues

James Gill and Howard Hunter

University Press of Mississippi / Jackson

The University Press of Mississippi is the scholarly publishing agency of the Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning: Alcorn State University, Delta State University, Jackson State University, Mississippi State University, Mississippi University for Women, Mississippi Valley State University, University of Mississippi, and University of Southern Mississippi.

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of University Presses.

Copyright 2021 by James Gill and Howard Hunter

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2021

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gill, James, author. | Hunter, Howard (G. Howard), author.

Title: Tearing down the lost cause: the removal of New Orleanss Confederate statues / James Gill, Howard Hunter.

Description: Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020053353 (print) | LCCN 2020053354 (ebook) | ISBN 978-1-4968-3332-7 (hardback) | ISBN 978-1-4968-3352-5 (epub) | ISBN 978-1-4968-3353-2 (epub) | ISBN 978-1-4968-3354-9 (pdf) | ISBN 978-1-4968-3351-8 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: StatuesLouisianaNew Orleans. | Soldiers monumentsSouthern States. | MonumentsPolitical aspectsSouthern StatesHistory21st century. | MonumentsSocial aspectsSouthern StatesHistory21st century. | Collective memoryPolitical aspectsSouthern StatesHistory21st century. | MemorializationPolitical aspectsSouthern StatesHistory21st century. | Racism in artPolitical aspectsSouthern StatesHistory21st century. | Community activistsSouthern StatesHistory21st century. | MonumentsUnited StatesPublic opinion. | New Orleans (La.)History. | United StatesHistoryCivil War, 1861-1865Monuments.

Classification: LCC E645 .G55 2021 (print) | LCC E645 (ebook) | DDC 976.3/35dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020053353

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020053354

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Writing about a city given to self-mythologizing is a daunting task, and we could not have completed the work without the support of individuals and institutions. We are also both immigrants to this new world of technology, and we would be remiss if we did not thank the brave souls who led us through that virtual and foreign territory.

Large sections of the book were written when we were more than four thousand miles apart. Thanks to the technology department at Metairie Park Country Day SchoolLinda Lawrence along with Sheila Pace and Bob OBriengeography became no object, and London could communicate with New Orleans. Faculty members Jennifer Marsiglia and Shay Steckler helped us set up interviews and manage the electronic content (both print and images) that we sent to the University Press of Mississippi.

We culled valuable content from various institutions. Country Day librarians Meb Norton and Chris Young secured the Alexander Doyle Papers from the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, a source that proved to be essential. Robert Ticknor, reference associate of the Williams Research Center, Historic New Orleans Collection, did a stand-up job helping us find the right images from the centers vast catalog. The Louisiana Research Collection of Tulane University is a treasure trove of primary sources in both print and images relating to the families and people who put up Confederate monuments. And we were fortunate that the Times-Picayune Archive worked with us to find excellent contemporary images.

Two remarkable artists contributed to the book. The New Orleans photographer Barry Kaiser donated his time and prodigious ability to capture the monuments in Greenwood and Metairie Cemeteries. An-My L generously allowed us to use her haunting image of the warehoused Beauregard and Lee statues, and Catherine Belloy of the Marian Goodman Gallery helped us gain access to the artists work.

We needed experts. To help us understand the psychological impact of defeat on Southern men, the eminent psychiatrist Richard Roniger, MD, generously shared his insights on the nature of psychic trauma. The geographer and author Richard Campanella of Tulane University, a perennial resource for understanding the New Orleans urban landscape, provided context on the politics of the monument removal. And, of course, chroniclers of New OrleansProfessor Lawrence Powell of Tulane University, the late Professor Judith Shafer of Tulane University, Professor Mark Fernandez of Loyola University, Professor Justin Nystrom of Loyola University, the author and historian John Kemp, and the historian and documentarian Jason Berryhave helped us negotiate a historical landscape fraught with myth.

Finally and most importantly, we wish to thank Catherine (Katie) Hunter, who found gems of newspaper stories we wove into the narrative; and Gail Gill, who tirelessly transcribed interviews.

TEARING DOWN THE LOST CAUSE

1

Robert E. Lee

An abrupt downpour washed out the event, but it could not forestall Robert E. Lees deification. On February 22, 1884, a crowd of fifteen thousand converged on Tivoli Circle in New Orleans to witness the unveiling of the Lee Monument. After Lees death in 1870, the Lee Monumental Association raised $10,000 for a young New York sculptor, Alexander Doyle, to create a sixteen-and-a-half-foot statue in bronze and raised an additional $26,000 for the local architect John Roy to erect a sixty-foot marble column set on top of a pyramidal base of granite. It was a prodigious accomplishment, considering that the city had suffered financial ruin in the Panic of 1873. The 104-foot structure, along with the Shot Tower (1883) and the New Orleans National Bank (1882), defined the cityscape when engineers were just beginning to master the challenge of building vertically on a high water table.

The Monumental Association included notables such as General P. G. T. Beauregard, CSA; Louisiana Supreme Court justice and Confederate veteran Charles Erasmus Fenner; and the cotton merchant Michael Musson, uncle of Edgar Degas. It was Carnival season, and the Committee of Arrangements organized the event like the tableaux of a Mardi Gras ball. Historians have marked the period between 1870 and 1914 as an era of invented tradition in which events were staged as if they were steeped in ancient ritual. The pageantry of the Lee memorial was the first of its kind, coming six years before Richmond followed suit. The program was to honor Robert E. Lee with a poem written specifically for the unveiling, as well as a lengthy oration by Judge Fenner. Three thousand chairs were set on the west side of the monument for ladies who arrived an hour before the festivities were to commence. On the platform were six hundred seats for big donors, nabobs, the Louisiana Supreme Court, members of Congress, the Monumental Association, and the Ladies Confederate Monumental Association; consuls-general of France, Great Britain, Germany, Mexico, the Netherlands, and the Dual Monarchy of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; and Confederate royalty, including Jefferson Davis and his two daughters; Lees two daughters, Mary and Mildred; and Mrs. T. S. Kennedy, the daughter of Confederate secretary of war Stephen Mallory. All the Confederate veterans groups, the associations of the Armies of Tennessee and Northern Virginia, and the Confederate States Calvary were represented; and significantly, in a spirit of reconciliation, two posts of the GAR (Union veterans of the Grand Army of the Republic), along with a National Guard unit from Detroit, were there by invitation. At the foot of the monument, the flags of the foreign consulates fluttered in the wind as a band struck up Richard Wagners Grand March Rienzi. But just as the proceedings were about to begin at 2:00, the sky grew dark, and a torrential rain drove the crowd indoors. Yet the veterans of the blue and gray were undeterred, and when two maimed veterans pulled a cord revealing the sculpture, a loud cheer went up.