Contents

Guide

African Founders

How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals

David Hackett Fischer

Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author of Washingtons Crossing

ALSO BY DAVID HACKETT FISCHER

Fairness and Freedom

Champlains Dream

Liberty and Freedom

Washingtons Crossing

Bound Away

The Great Wave

Paul Reveres Ride

Albions Seed

Growing Old in America

Historians Fallacies

The Revolution of American Conservatism

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2022 by David Hackett Fischer

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition May 2022

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Paul Dippolito

Jacket design by Math Monahan

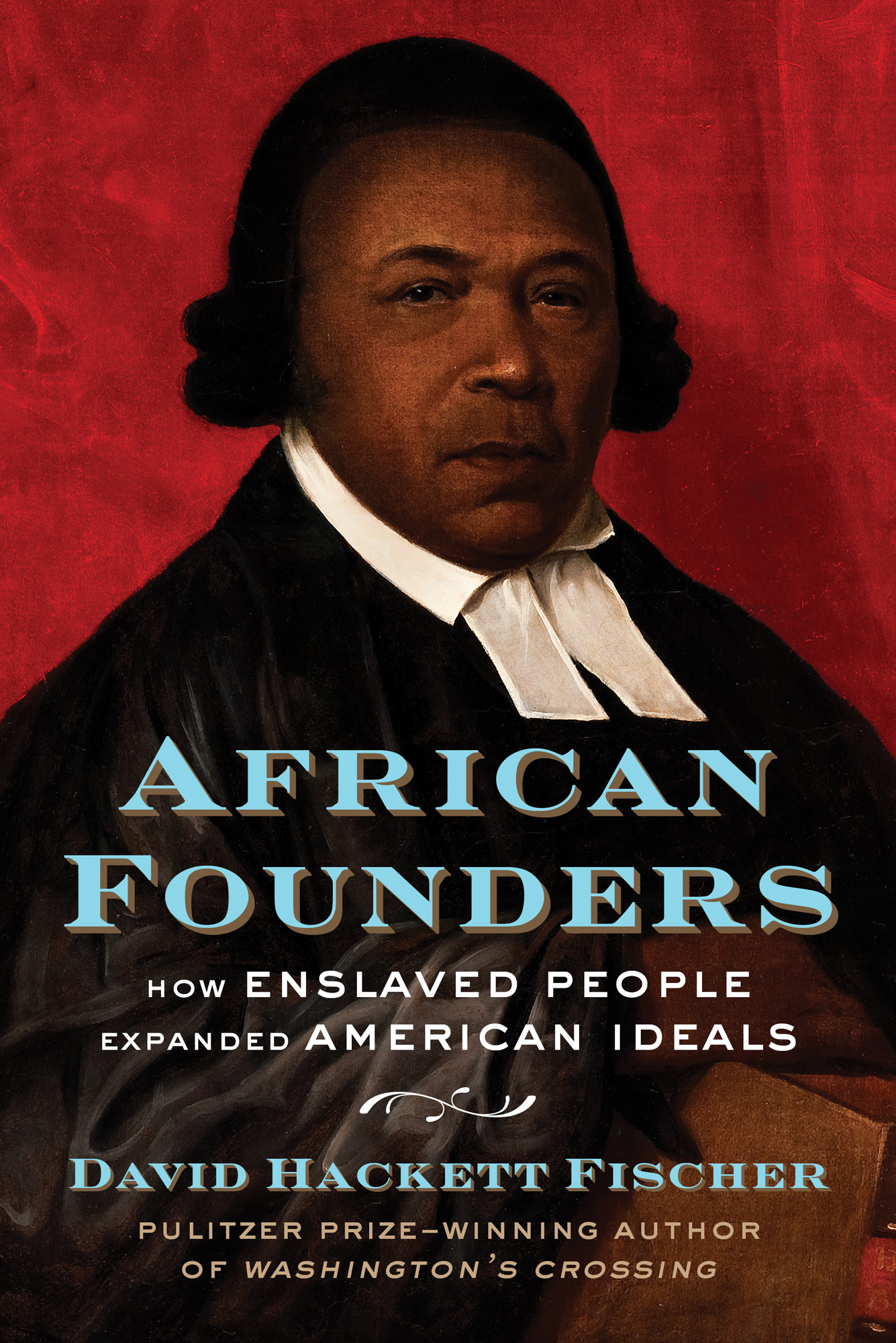

Jacket art (Front): Portrait of Absalom Jones by Raphaelle Peale; (Back): Peter Williams (17501823) by Unidentified Artist, Ca. 18101815, Collection of The New-York Historical Society; Harriet Tubman by Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images; Portrait of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo by William Hoare; Phillis Wheatley by Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-9821-4509-5

ISBN 978-1-9821-4511-8 (ebook)

For Suzy, Annie, and Judy, with love

TABLES

Introduction

Chapter 3: Delaware Valley

Chapter 4: Chesapeake Virginia and Maryland

Chapter 5: Coastal Carolina and Georgia

Chapter 6: Louisiana, Mississippi, and the Gulf Coast

Chapter 9: Southern Frontiers

- Credit information for the tables can be found on pages .

INTRODUCTION

Slavery time was tough, it like looking back into de dark, like looking into de night.

Amy Chavis Perry, former slave in Charleston, S.C.

The slave is in chainsbut how is one to eradicate his love of liberty? How is one to blot out his intelligence, which he might possibly use to break his bonds?

Gustave de Beaumont, 1835

O N MAY 11, 1831, two lively young aristocrats strolled down the gangway of the steamship President into the swirling chaos of lower Manhattan. Officially, Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont had come to study American prison systems. Unofficially, another purpose was to keep out of a French prison themselves, after the Revolution of 1830.

For nine months, these French visitors made an intellectual tour of the American republic. Doors flew open to them everywhere. They visited most regions in the country, talked with many people, and wrote very different books on what they learned in the New World. Tocqueville published his great and hopeful treatise on democracy in America, and its future in Europe. Beaumont brought out a tragic novel on the persistence of slavery in the United States, the progress of racism in America, and its growth in the modern world.

Both men were amazed by the contradictions they observed in the same society, and even in the same scenes. In the United States, they found that the rule of law coexisted with savage violence. They discovered throughout America a broad equality of manners and deep inequality of wealth. Most of all, they were astonished by the coexistence of freedom with slavery, and equality with racism. Surely it is a strange fact, Beaumont wrote, that there is so much bondage amid so much liberty.

That paradox has long been near the center of American history, and it has been studied in different ways. From the early nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, six generations of American scholars were mostly Whig historians of their nation. Their work tended to center on ideas of liberty and freedom, equal rights and republican self-government. Major themes were the triumph of those ideas and institutions over tyranny and slavery.

In the United States, these Whig historians celebrated the prohibition of the foreign slave trade by Congress, which took effect on January 1, 1808, the first day when it could be forbidden under the federal Constitution. They praised Abraham Lincolns Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, five days after the Union victory at Antietam.

Whig historians also honored the abolition of slavery by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. They acclaimed the prohibition of racial injustice by the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, which made citizens of all persons born or naturalized in the United States and entitled them to equal protection of the laws with no distinctions of race. And they praised the Fifteenth Amendment in 186970, which prohibited the denial or abridgment of the right to vote in the United States on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Major questions for Whig historians were about sources of strength in American values and institutions, and how they might be made stronger. Failures were closely studied, and limits were fully discussed, but the prevailing mood of Americas leading scholars tended to be optimistic from the nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, with exceptions such as Henry Adams, Brooks Adams, and the later work of Charles Beard.

Then, in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the purposes of American historians began to change. New generations of scholars continued to study the same subjects, but in a very different spirit. Their work tended to center less on American liberty, freedom, equality, and democracy. It gave more attention to American slavery, racism, inequality, injustice, and corruption. Major questions in academic discourse were increasingly about the roots of racial oppression, the corruption of capitalism, the decay of political institutions, the failure of reform movements, and the decline of American leadership. With many important exceptions, the tone of much American historical writing turned deeply negative during the early twenty-first century. It remained so as these words were written, in 2021.

ANOTHER FRAME OF HISTORICAL THINKING: NEW USES FOR AN OLD IDEA OF HERODOTUS

This project takes yet another approach. It returns to the history of what is now the United States, but does not begin with predominantly positive or negative judgments about the main lines of American history. Instead, it starts with a different set of ethical assumptions. One is that slavery, racism, and racial oppression in many forms have long been great and persistent evils in America and the world. Another is that vibrant traditions of freedom and liberty and the rule of law have long continued to be sources of enduring strength, especially in the United States, most of all in our own time.