ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

No one can write a book without help from a lot of other people. This one would never have happened without the continuing support of Stanford Universitys School of Humanities and Sciences or the generosity of the Carnegie Foundation, which supported the early stages of my research with an Andrew Carnegie Fellowship.

I owe an enormous debt to Martin Carver, Nick Clegg, Simon Esmonde-Cleary, Ian Hodder, Phil Kleinheinz, Mark Malcomson, Brook Manville, Jared McKinney, John OBrien, Josh Ober, Mike Parker Pearson, Neil Roberts, Steve Shennan, Brendan Simms, Kathy St John, Matthew Taylor and Greg Woolf. All read and advised on parts or even the whole of the book in manuscript form, although they should not be held responsible for what I did with their advice. Invitations to spend parts of the academic year 201516 as the Philippe Roman Professor of International Studies at the London School of Economics and part of the summer of 2019 as the Australian Armys Keogh Professor of Future Land Warfare shaped my thinking in major ways. I also benefited greatly from invitations from George Hammond (Commonwealth Club of California), Mark Malcomson (City Lit), Freddie Matthews (British Museum) and Katie Zoglin (World Affairs Council) to give public lectures for their organisations, and from Brendan Simms to attend the Centre for Geopoliticss online seminars.

Shan Vahidy was an exemplary and wise editor, Michele Angel drew the wonderful maps and charts, Penny Daniel saw everything through production smoothly and Valerie Kiszka untangled multiple muddles I created, as she so often does. Andrew Franklin at Profile Books and Eric Chinski at Farrar, Straus & Giroux patiently dispensed advice and kept the whole thing moving, despite my delays and abrupt changes of direction; and Sandy Dijkstra, Elise Capron and Andrea Cavallaro at the Sandra Dijkstra Literary Agency and Rachel Clements at Abner Stein provided the perfect amount of support. My thanks to you all.

ALSO BY IAN MORRIS

The Measure of Civilisation

War: What Is It Good For?

Why the West Rules for Now

1

THATCHERS LAW, 60004000 BCE

Catch-22

We are inextricably part of Europe, Margaret Thatcher told Britain in 1975. Neither Mr Foot nor Mr Benn the chief Brexiteers of the day nor anyone else will ever be able to take us out of Europe, for Europe is where we are and where we have always been.

This may sound odd, given Mrs Thatchers later reputation as the arch-enemy of European integration, and some historians do wonder whether she really meant it. After all, she had just taken over a Conservative Party whose biggest recent success had been taking Britain into the European Community; now that a Labour government was putting this achievement to a referendum, honour surely required her to defend it. Yet, whatever Thatchers inner qualms (to which we will return in ), her advice to the nation on the eve of the first Brexit referendum laid bare, as well as anyone has ever done, the fundamental facts of Britains position. So compelling is her claim that Britain is inextricably part of Europe and cannot be taken out of it, for Europe is where Britain is and where it has always been that I am going to call it Thatchers Law.

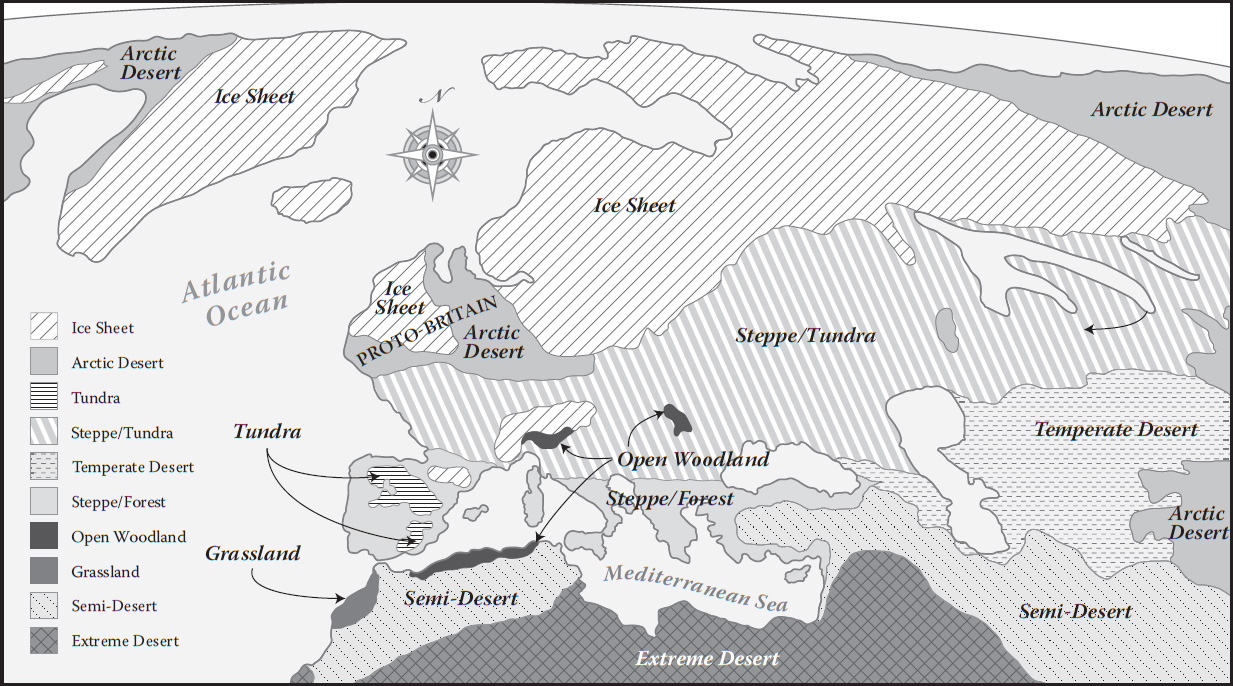

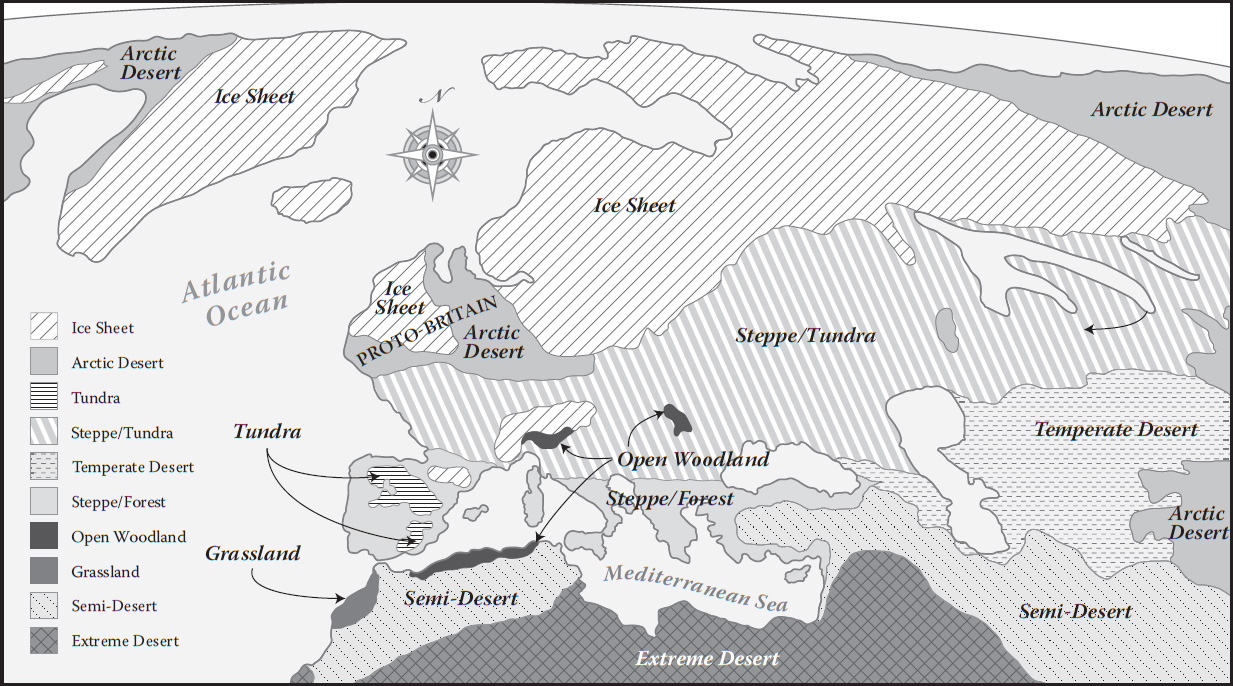

Like all scientific laws, Thatchers has exceptions. Britain has not really always been in Europe, because there has not always been a Europe to be in. Our planet has existed for 4.6 billion years, but shifting continental plates only began creating what we now call Europe about 200 million years ago. That caveat aside, however, Britain was very literally part of Europe for 99 per cent of these 200 million years, because the Isles were not islands at all but one end of a great plain stretching unbroken from Russia to an Atlantic coastline lying 150 km west of modern Galway (). For want of a better name, I will call this huge, ancient extension of the Continent Proto-Britain.

During the multiple ice ages which filled much of the last 2.5 million years, glaciers sucked so much water out of the oceans that what we now know as the North Sea and Eastern Atlantic were largely above sea level. At the coldest point, 20,000 years ago, temperatures averaged 6 C cooler than today. Ice sheets up to 3 km thick covered much of the northern hemisphere, trapping 120 million billion tons of water and leaving the sea level 100 m lower.

Figure 1.1. The expansion of Europe: coastlines and glaciers at the coldest point of the last ice age, around 20,000 years ago.

Nothing could live on the glaciers that blanketed the future Scotland, Ireland, Wales and northern England at the coldest points of the last ice age, and the tundras which stretched 150 km or more beyond their southern edge were scarcely more welcoming. At some points ice locked up so much moisture that barely one-fifth as much rain fell as nowadays and the air carried ten to twenty times as much dust. Even more than the cold, this aridity meant that very few plants could grow in Proto-Britain, and so there were very few animals around eating them, and no people at all eating anything.

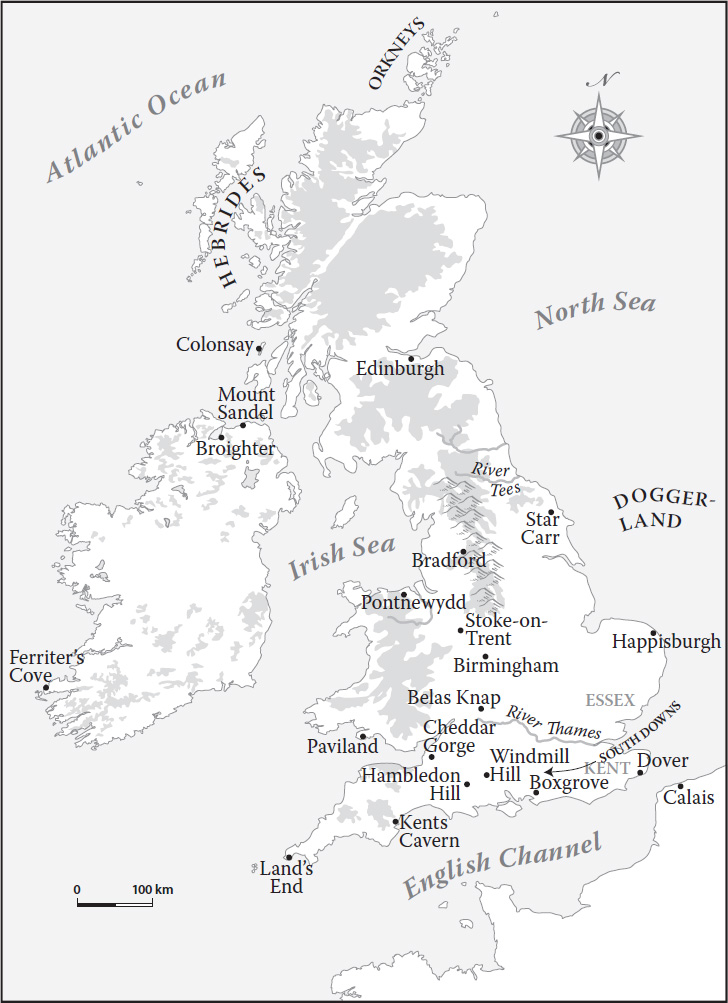

The first human-like apes (anthropologists argue endlessly over how to define human) evolved on East Africas savannahs around 2.5 million years ago, immediately creating the original geostrategic imbalance. The pattern that we will see over and over again in this book, of imbalances arising in one place and evening out across space, is therefore as old as humanity itself. In this case the evening out took hundreds of thousands of years, as proto-humans migrated into previously humanless parts of Africa. However, in another pattern that we will keep seeing, new imbalances were created as fast as earlier ones evened out, because new kinds of humans went on evolving, whether back in the original East African homeland or from interbreeding among the humans spreading into Asia and Europe. By 1.5 million years ago, people who could communicate in complicated ways even if what they did was not exactly talking had fanned out as far as Indonesia, China and the Balkans. Only during warmer, wetter breaks in the ice ages could they work their way further across Europe, but in one of these periods, nearly a million years ago, the first proto-humans wandered into Proto-Britain.

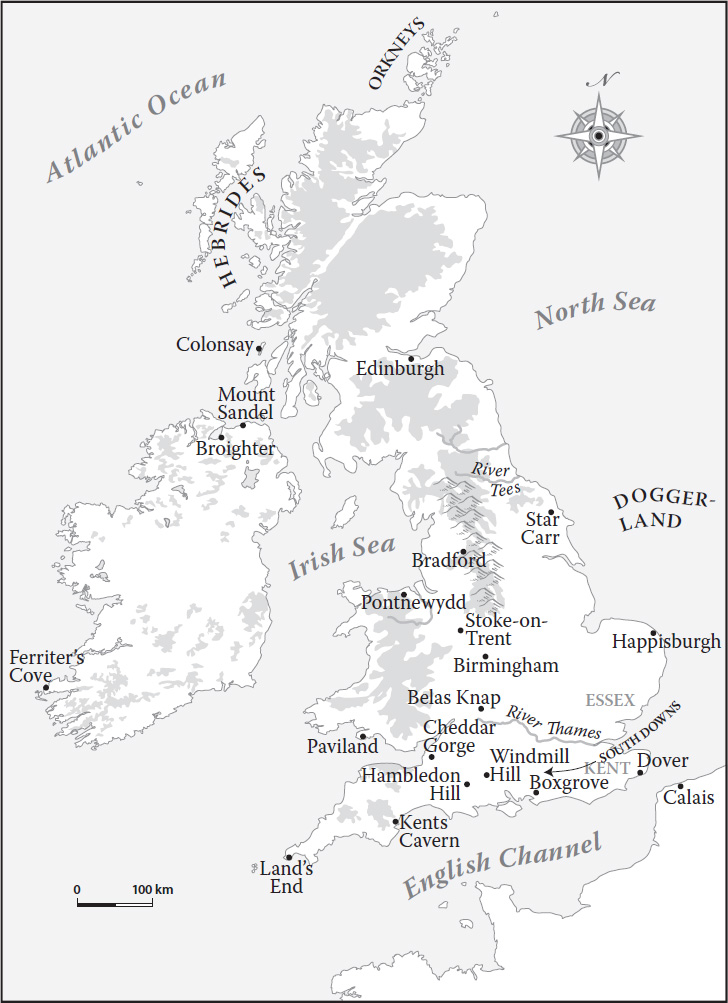

The evidence comes from a tangle of footprints on a muddy tidal riverbank at Happisburgh (pronounced, because this is England, Hazebruh) in Norfolk (). After being buried by drifting sand, the mud hardened, preserving the tracks until 2013, when storms washed away the material covering them. Within two weeks the waters had washed away the footsteps too, but that was long enough for archaeologists to pounce and record every detail earning, quite rightly, Current Archaeology magazines Rescue Dig of the Year award.

Figure 1.2. The British stage, 1,000,000 BCE to 4000 BCE (on a map showing modern coastlines).

There is no way to date a footprint, but we do have two techniques for fixing in time the mud into which those ancient feet sank. We can get a rough sense from magnetised particles in the mud, because every 450,000 years or so the earths magnetic poles reverse direction. When the Happisburgh mud was laid down, a compass needle would have pointed towards what we now call the South Pole, suggesting that the mud is close to a million years old; and we can sharpen that up with the second technique, looking at fossils (above all, voles teeth) in the sediments, indicating a date 850,000950,000 years ago.