Center for Korea Studies Publications

The Northern Region of Korea: History, Identity, and Culture

Edited by Sun Joo Kim

Reassessing the Park Chung Hee Era, 19611979: Development, Political Thought, Democracy, and Cultural Influence

Edited by Hyung-A Kim and Clark W. Sorensen

Colonial Rule and Social Change in Korea, 19101945

Edited by Hong Yung Lee, Yong Chool Ha, and Clark W. Sorensen

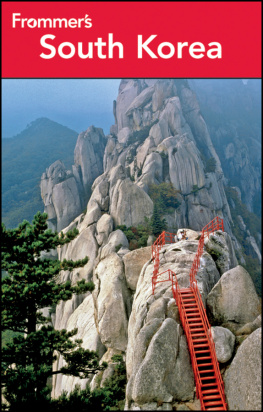

An Affair with Korea: Memories of South Korea in the 1960s

By Vincent S. R. Brandt

This work was supported by the Academy of Korean Studies (KSPS) Grant funded by the Korean Government (MOE) (AKS2011BAA2101).

(AKS-2011-BAA-2101).

The Center for Korea Studies Publication Series is dedicated to providing excellent academic resources and conference volumes related to the history, culture, and politics of the Korean peninsula.

Clark W. Sorensen | Director & General Editor | Center for Korea Studies

An Affair with Korea: Memories of South Korea in the 1960s

By Vincent S. R. Brandt

Photographs by Vincent S. R. Brandt

2014 by the Center for Korea Studies, University of Washington

Printed in the United States of America

18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the publisher.

CENTER FOR KOREA STUDIES

Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies

University of Washington

Box 353650, Seattle, WA 98195-3650

http://jsis.washington.edu/Korea

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

P.O. Box 50096, Seattle, WA 98195 U.S.A.

www.washington.edu/uwpress

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Brandt, Vincent S. R.

An affair with Korea / Vincent S.R. Brandt. First edition.

pages cm

Summary: In 1966 Vincent S. R. Brandt lived in Sokp'o, a poor and isolated South Korean fishing village on the coast of the Yellow Sea, carrying out social anthropological research. At that time, the only way to reach Sokp'o, other than by boat, was a two hour walk along foot paths. This memoir of his experiences in a village with no electricity, running water, or telephone shows Brandt's attempts to adapt to a traditional, preindustrial existence in a small, almost completely self-sufficient community. This vivid account of his growing admiration for an ancient way of life that was doomed, and that most of the villagers themselves despised, illuminates a social world that has almost completely disappeared. Vincent S. R. Brandt lives in rural VermontProvided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-295-99341-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Brandt, Vincent S. R. 2. VillagesKorea (South)Case studies. 3. Fishing villagesYellow Sea Coast (Korea) 4. FishersYellow Sea Coast (Korea) 5. Maritime anthropologyYellow Sea Coast (Korea) 6. Yellow Sea Coast (Korea)Description and travel. 7. Ch'ungch'ong-namdo (Korea)Rural conditions20th century. 8. Ch'ungch'ong-namdo (Korea)Social life and customs20th century. 9. AmericansKorea (South)Korea (South)Biography. 10. AnthropologistsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

HN730.5.A8B725 2013

306.09519dc23 2013032302

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials,

ANSI Z39, 48-1984.

ISBN-13: 978-0-295-80476-7 (electronic)

For Hi Kyung, my North Korean refugee

Preface

I spent most of 1966 in Skp'o, a poor and isolated fishing village on the Yellow Sea coast of central South Korea, carrying out social anthropological research. At that time the only way to get to Skp'o, except by boat, was to walk for two hours from where the bus line ended further down the coast. There were no roads, only foot paths. And, of course, there was no electricity, running water, or telephone. This book is an informal memoir of that experience. The focus is not so much on the anthropological findings, as it is on my personal involvementmy attempt to adapt to a traditional, pre-industrial existence in a small, almost completely self-sufficient community. Further, it is an account of my growing admiration for an ancient way of life that was doomed, and that most of the villagers themselves, while still governed by its dictates, despised. It is also about how the residents of Skp'o coped with the strange challenge of having a foreigner live in their midst. In the prologue I have tried to place Skp'o in the social and economic context of contemporary South Korea, and finally in the final chapter titled Re-encounter, I have summarized my impressions of Skp'o when I returned there for three months twenty-five years later. Today (2013) the rapid pace of development and change in South Korea continues. Living standards continue to climb. The social world of Skp'o described in this book has almost completely disappeared.

NOTES

. My anthropological monograph, entitled A Korean Village: Between Farm and Sea, was published in 1971 by Harvard University Press.

Prologue

When visibility is good, the approach to Kimp'o Airport just outside Seoul provides spectacular scenery. It also brings back all sorts of wonderful memories that have piled up in the course of a great many trips to Korea since 1952. Seoul has always been for me both exotic and familiar, a place where unexpected adventures were usually lying in wait, but where I could also count on old friends to put me up for the nightor for a weekwithout advance notice.

During the Korean War, I was a young diplomat at the American Embassy, first in Pusan and then, from February of 1953, in Seoul. Those were the very worst of times for Koreans, but a halcyon period for me. In the Pusan area of the south I had a fascinating job, roaming through the most distant and isolated parts of a mountainous countryside with a Jeep and interpreter. My assignment was to check up on the distribution of relief grain and run down reports of rural starvation that appeared frequently in the Pusan newspapers. Perhaps halcyon isn't quite the right word to describe the experience of being shot at by guerillas. On one very memorable occasion we were driving along a deserted mountain road at dusk. One bullet hit the hood of the Jeep and another broke the windshield. The terrified driver whipped the Jeep around and headed back the way we had come without any orders from me. Combat police at the nearest town told us this only happened late in the day when the guerillas figured they were safe from pursuit by Army helicopters. After that we stopped driving well before suppertime and no longer spent the night in isolated villages.

In those towns and villages, my interpreter, who became a close friend, introduced me to rural life and entertainments. I learned to eat with chopsticks, sleep on the floor, and take baths out of a giant cauldron with a wood fire underneath. I learned to drink various homemade alcoholic beverages and to sing folk songs along with the local female entertainers. Because American officialdom firmly believed that all Korean food was dangerously unhealthy, each time we left Pusan the Jeep was loaded with C-rations. Instead of eating these, we benevolently distributed them to local farmers in return for information, directions, food, drink, and lodging. In place of canned pork and beans we ate fresh greens with hot bean paste sauce and kimch'i or tofu mixed with various vegetables and meat. On one occasion when the sub-county magistrate was being particularly hospitable, the meat turned out to be dog.

(AKS-2011-BAA-2101).

(AKS-2011-BAA-2101).