Copyright 2003 by John Feffer

Open Media series editor, Greg Ruggiero.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means, including mechanical, electric, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

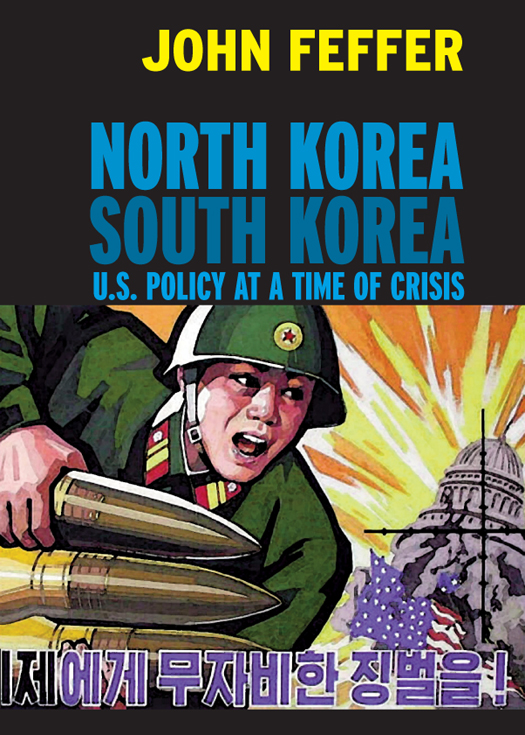

Cover design: Greg Ruggiero

Cover image: Contemporary North Korean propaganda poster

eISBN: 978-1-60980-274-5

v3.1

For Karin, partner in everything.

Contents

INTRODUCTION

The Current Crisis

It was a striking juxtaposition: U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and North Korean leader Kim Jong Il sitting side by side at a display of mass gymnastics in October 2000. Spectacular and amazing, Albright called the coordinated movements of the one hundred thousand performers in the stadium in Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea. When a picture of a 1998 rocket launch was displayed before the audience, Kim Jong Il leaned over to confide that it would be his countrys first and last such launch. Later the two would toast one another at a state dinner, and the photo appeared on the front pages of many newspapers. Albright announced to the international press that Kim Jong Il was a man with whom Washington could do business: very decisive and practical and serious. She recommended that Bill Clinton make the first presidential visit to North Korean before the years end to trade a package of economic incentives for an end to North Koreas missile program. The United States and its longest running enemy, technically at war for over fifty years, appeared to be finally approaching detente.

Madeleine Albright was no starry-eyed dove. Long before joining the Clinton administration, the Czech-born Albright had acquired a hawkish reputation as a Sovietologist and served with her mentor Zbigniew Brzezinski on the National Security Council in the late 1970s. In her first four weeks as Bill Clintons secretary of state, she lectured the The cold war in Asia, which had already outlasted its European counterpart by a decade, was entering a new warm spell. Albright sensed a diplomatic breakthrough in the offing and wanted to go down in history with her president as resolving one of the thorniest problems in U.S. foreign policy.

Albright and Clinton did not make history in the fall of 2000.

On her return to Washington, Albright scrambled to defend her reticence to raise human rights issues with Kim Jong Il. Pundits lambasted Clinton for overreaching himself in Korea to save his foreign policy legacy from the flames engulfing the Middle East. And follow-up talks in Malaysia between the United States and North Korea failed to yield an agreement on the missile issue. As the U.S. presidential elections headed into a procedural snafu in Florida in November 2000, Clinton decided not to risk a visit to Pyongyang. He extended a secret invitation to Kim Jong Il to visit Washington instead, but this last-minute attempt to save a deal also went nowhere.

And today, roughly three years later, the United States and North Korea are on the verge of war. How in this short time did these two countries make such a hash of their reconciliation?

The proximate cause of the current crisis was the revelation in October 2002 that North Korea was still trying to acquire nuclear weapons despite a pledge to abstain. Under a 1994 agreement, North Korea shut down its nuclear reactors and plutonium reprocessing facility at Yongbyon in exchange for heavy fuel oil, two light-water nuclear reactors, and movement toward diplomatic recognition. In 2002, the Bush administration accused North Korea of covertly working with Pakistan on a second path to a nuclear bomb. After making its allegations about this secret uranium enrichment program, the Bush administration ended all heavy fuel oil shipments to North Korea. North Korea in turn declared on 10 January 2003 that it was no longer party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)a withdrawal that went into effect three months laterand threatened as well to pull out of the armistice agreement that put an end to the fighting in the Korean War.

As the crisis deepened, North Korea sent out signals that it wanted to return to the status quo ante. It announced that it would consider rejoining the NPT if the United States resumed the oil shipments. It would suspend its nuclear program if the United States signed a nonaggression statement. Washington ignored these offers. While maintaining that it wanted a diplomatic solution to the conflict, the United States refused to sit down with North Korea for one-on-one negotiations. Although contemptuous of multilateralism

By March, North Korea was preparing to restart its plutonium facility. The war in Iraq had led the leaders in Pyongyang to draw three conclusions: a nonaggression agreement with the United States was pointless, no inspection regime would ever be good enough for Washington, and only a nuclear weapon would deter a U.S. intervention. Meanwhile, North Korea has announced that an embargo or a policy of naval interdiction would be tantamount to a declaration of war.

This is no minor disagreement. Geopolitics has rendered the Korean peninsula one of the most highly militarized areas of the world. The demilitarized zone separating the two Koreas is perhaps the most dangerous trip wire in the world, what Bill Clinton dubbed the scariest place on earth on a visit there in 1993. It is a war waiting to happen. Although the great powers in the regionChina, Japan, and Russiado not want such a war, they may get drawn in despite their best intentions. As such, the current conflict between the United States and North Korea has profound international implications.

The current crisis is not, as the Bush administration suggests, simply a result of North Koreas persistent desire to obtain nuclear weapons. Nor has the crisis caught the Bush administration without a coherent policy in place. Contrary to the claims of administration figures, Bush did not adjust policy midstream in response to new information and a new calculation of the threat from North Korea. As this book will demonstrate, the current policy on North Korea was incubating in conservative policy circles during the 1990s. Once in power, the Bush administration has used various means to pursue its ultimate goal: regime change in Pyongyang.

Toward this end, the administration has campaigned against any policies that might extend the life of the current North Korean government, from the 1994 Agreed Framework to South Koreas engagement policy. The Bush team has so far relied on economic containment and diplomatic nonengagement to bring down the North Korean government. Should these strategies prove insufficient, the administration has drawn up several military scenarios that, in keeping with a new nuclear doctrine, may involve the first use of nuclear weapons. As such, Bush policy on North Korea is of a piece with the more profound doctrine shift in U.S. foreign policy that the administration was

The Bush administration decisively repudiated the Clinton-Albright approach that was so dramatically advanced in Pyongyang in October 2000. But the flaws of U.S. policy toward North Korea did not suddenly appear when George W. Bush took office in January 2001. The carrot-and-stick strategy that dominated U.S. policy toward North Korea in the 1990s established a dynamic of mistrust, misunderstanding, and missed opportunities that provided a weak foundation for the brief dtente of 2000. The logical incoherence of the Clinton-Albright approachin part a result of conservative resistance to engagement with North Korea from elements of Congress, the Pentagon, the intelligence community, and the State Departmentmade it easier for the Bush team to destroy one of the few positive elements of the Democrats foreign policy legacy.