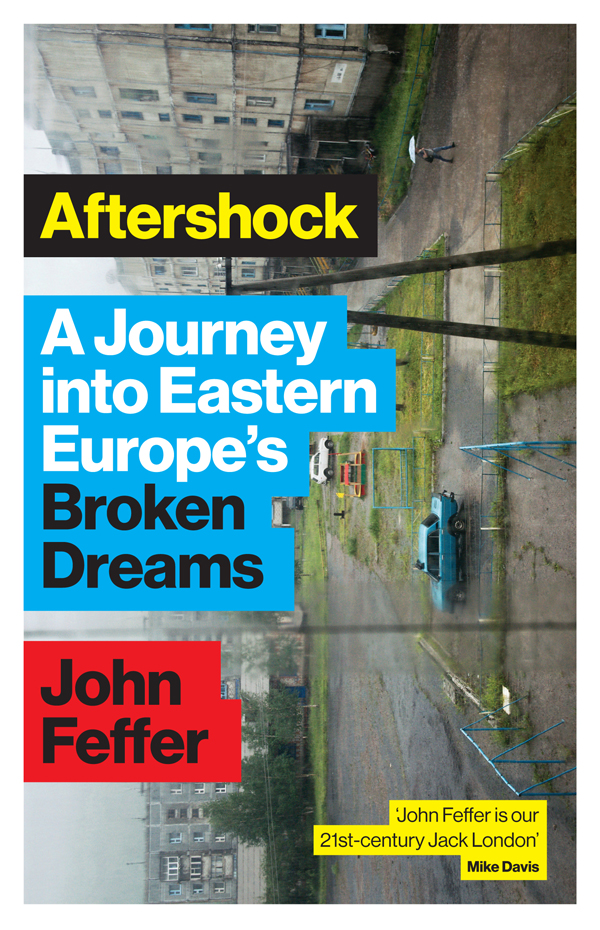

More praise for Aftershock

A brisk, vivid and wide-ranging survey of a region in the grip of neoliberalism. As Feffer makes clear, this is hardly just a book about Eastern Europe, as the challenges there now seem to be spreading throughout the world. Feffers sense of the future evinces both pessimism of the mind and optimism of the will.

Lawrence Weschler, author of Vermeer in Bosnia and Calamities of Exile

A breath-taking whirlwind tour through the transformations of eastern Europe over the past 30 years. With its account of the travails of contemporary capitalism, is also astonishingly relevant for understanding pressing political problems in the United States as well.

David Ost, author of The Defeat of Solidarity: Anger and Politics in Post-Communist Europe

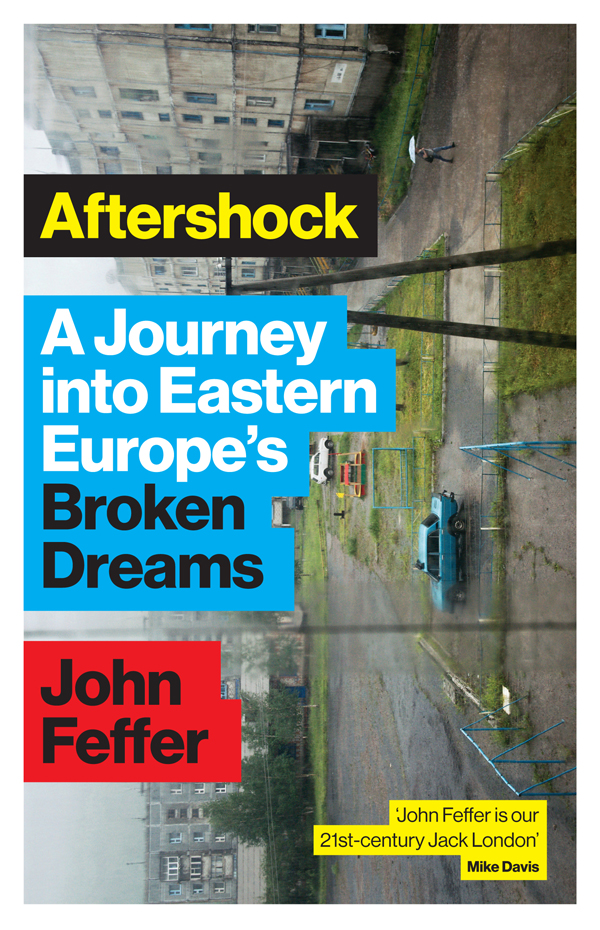

Aftershock

A Journey

into Eastern

Europes

Broken

Dreams

John Feffer

Aftershock: A Journey into Eastern Europes Broken Dreams was first published in 2017 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK

www.zedbooks.net

Copyright John Feffer 2017

The right of John Feffer to be identified as the author of this work have been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

Typeset in Haarlemmer by seagulls.net

Index: John Feffer

Cover design: David A. Gee

Cover photo Elena Chernyshova/Panos

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78360-949-9 hb

ISBN 978-1-78360-948-2 pb

ISBN 978-1-78360-950-5 pdf

ISBN 978-1-78360-951-2 epub

ISBN 978-1-78360-952-9 mobi

Contents

This book is dedicated to all the amazing people that sat down with me in 1990, in 2012/13 and occasionally at points in between and answered my questions with candor and great intelligence. All of the interviews quoted in the text are available, in full, on my website at: www.johnfeffer.com/full-interview-list

Some of these interviewees have passed away since I spoke with them just a few years ago. It is with great sadness that I record their names here: Ale Debeljak, Miroslav Durmov, Nicolae Gheorghe and Kurt Ptzold.

This book would not have been possible without the generous support of the Open Society Foundation, which funded my return to eastern Europe as an Open Society Fellow in 2012/13. Id also like to thank the Institute for Policy Studies for allowing me to take a leave of absence to do this work.

Id like to thank the following people for reading portions of the manuscript and offering their comments: Mladen Jovanovi, Vihar Krastev, Miroslav Krupika, Bogdan apiski, Margareta Matache, Mira Oklobdzija, David Ost, Sara Pistotnik, Bartosz Rydliski, Nea Kogovek alamon, Ivan Vejvoda, Maria Yosifova, and Jelka Zorn. My editor at Zed, Ken Barlow, also provided excellent recommendations throughout the editorial process. Whatever errors escaped this vetting process are mine alone.

Id also like to thank all the people who helped arrange meetings and provide interpretation: Iskar Enev and Vihra Gancheva (Bulgaria), Hrvoja Heffer (Croatia), Sarah Bhm and Adrian Klocke (Germany), Judit Hatfaludi (Hungary), Ewa Maczynska and Anna Maria Napieralska (Poland), Dan Iepure (Romania), Pavol Kustar and Alena Pnikov (Slovakia).

Finally, my wife Karin Lee accompanied me on virtually every step of this project, making it possible for me to return to the region, reviewing the manuscript, and providing astute suggestions along the way. She remains my ideal reader.

It was not easy to find Miroslav Durmov.

There were plenty of references to him on the Internet, but the trail went cold in the mid-1990s. Probably hed just dropped out of politics and returned to private life. More ominously, he might have died, as had several other people Id interviewed in eastern Europe in 1990. But I didnt turn up an obituary. I wanted to find Miroslav because I was planning to return to Bulgaria. I hoped to interview him again after nearly twenty-five years to see how his life and his thinking had changed in the interim.

When I first met Miroslav in August 1990, he occupied an unusual and prestigious position. He was one of the top people in the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (MRF), a new political formation that was officially devoted to the human rights of all Bulgarians. In reality, the Movement focused on the rights of ethnic minorities, primarily the ethnic Turks who make up 10 percent of Bulgarias population. What made Miroslavs position unusual was that he himself wasnt an ethnic Turk. A psychologist and lawyer by training, hed become acquainted with the ethnic Turkish community through marriage. He was incensed by the indignities the communist government had forced upon its ethnic Turkish citizens, first insisting that they Slavicize their names in 1984 and then kicking more than 300,000 of them out of the country in the spring and summer of 1989. Ethnic Turkish activists had formed the MRF to redress these wrongs.

In 2013, the MRF was still a political force in Bulgaria significant enough to determine the composition of coalition governments. But Miroslav Durmov, who had struck me as one of the rare politicians who could successfully make the transition to the new democracy, was nowhere to be found. In the Internet archive of Bulgarian newspapers, I followed the trajectory of his political career. He was mentioned quite frequently in the early 1990s as a spokesman for the MRF. Then he led the Movements parliamentary faction. Then he split from the Movement and created his own political party.

And then he disappeared.

In desperation, I turned to everyones last resort for tracking down former college roommates and old flames. I found Miroslav Durmov on Facebook. But he was in the wrong place and doing the wrong thing. This other Miroslav Durmov was living in Lexington, Kentucky, and working in an Amazon fulfillment center. On a whim, I sent this other Miroslav a note in the hope that he would know something about his namesake back in Bulgaria.

They turned out to be one and the same person.

Miroslav, I discovered, had moved to the United States at the age of fifty. He and his wife had arrived in New York City with virtually no English, no job prospects, and only one slender hope for the future: the contact information of a cousin. New York was a dazzling, cosmopolitan city with a Bulgarian community large enough at the time to support its own newspaper. It was also a very expensive place to live. Even with the help of this cousin, Miroslav and his wife didnt have enough money to survive in the Big Apple. They heard from a fellow migr that Kentucky was cheap. So, off they went.

A few blocks from Lexingtons Main Street, they found a modest two-story house. Miroslav worked in a succession of poorly paid clerical and factory positions while his wife Maria Yosifova, a lawyer back in Bulgaria, started out as a housekeeper. They just managed to make ends meet even as they studied English and returned to school to get new college degrees. They pinned their hopes on their two teenage sons, who were thriving as transplants. Like many immigrants, Miroslav and his wife were making sacrifices for the next generation.

Miroslav was one in a million. Quite literally. The population of Bulgaria on the eve of the changes that took place in 1989, when eastern Europe went through its year of miracles, was nearly nine million people. That number had dropped to just a little over seven million by 2015. More than a million people left Bulgaria after 1989. Combined with a startling drop in fertility from nearly two children per woman in 1989 to only one child by 1997 In the black humor characteristic of the region, Bulgarians like to ask: what are the only two ways to escape our countrys crisis? The answer: Terminal One and Terminal Two. Its not really a joke. The airport in Sofia had emerged as Bulgarians most popular economic development strategy.

Next page