Acknowledgments

This book would not have been possible without the assistance of Michelle Kim, Minsuh Son, and Kim Yong-kyu, and the editing skills of Steve Mockus. I am indebted to them and to the Korean people I had the good fortune to meet on both sides of the 38th parallel.

by Bruce Cumings

Of all the slogans the traveler sees in North Korea, maybe the most poignant is the one that hangs above the main square (and can be seen in many other places): We have nothing to envy in the world. It simultaneously fits the regimes propaganda about its paradise and leads us to ask, how would any North Korean citizen know if there might be something to envy in the rest of the world? They cant even travel from the countryside to Pyongyang without a permit, and only the most reliable can travel abroad.

Mark Edward Harriss wonderful collection of photographs illustrates that North Korea does have some enviable features. When we view the awe-inspiring crater lake on White Head Mountain (Paektusan), revered as the mythical fount of the Korean people, we come to understand that one of the worlds most beautiful panoramascomparable to Mt. Fuji or Mt. Rainier, near Seattlehas been off-limits to Western tourists since 1945 because of the persistent division of this peninsula. The same was true of the Diamond Mountains (Geumgangsan), with scenery as compelling as Yosemite, until a South Korean firm got permission to bring thousands of tourists to see these mountains (and hardly anything else, of course).

Then we see a different kind of monument: a subway station with shiny walls, spic-and-span floors, and extravagant chandeliers. I once toured the subway with an eerie feeling that I was in a cathedral. Each station-sanctuary played out a theme, in lavish marble and painstakingly done inlaid tile: the harvest station, for example, shows Kim Il Sung standing amid an abundant corn harvest. The shimmering porcelain was lit by chandeliers made of glass goblets done in lime green, hot pink, and bright orange, meant to represent bunches of fruit. Then I looked at the faces of the people on the subway, some of them friendly, some of them unmistakably scornful, most of them careworn and blank. We see some of them in Harriss book: nothing to envy in the world?

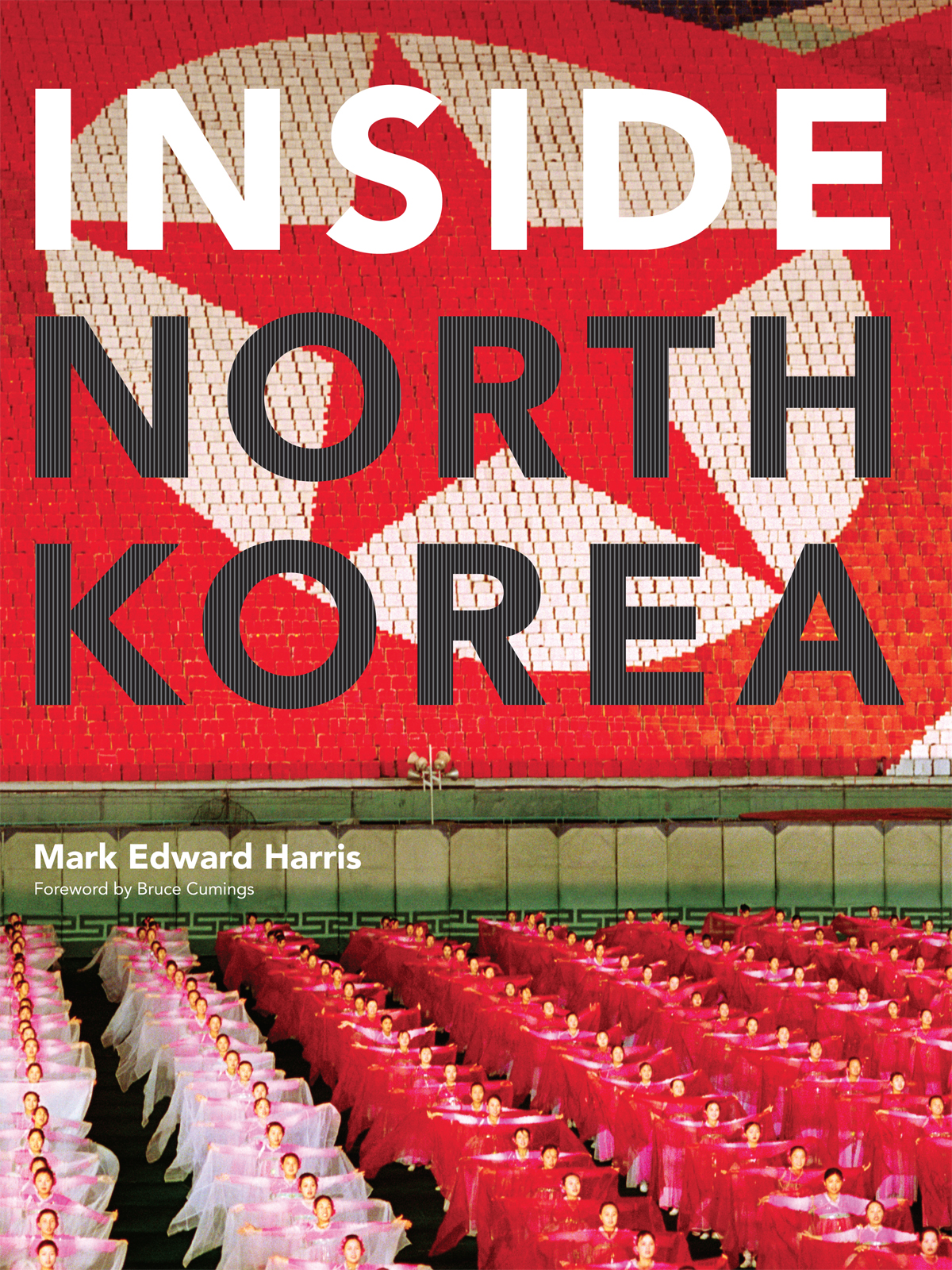

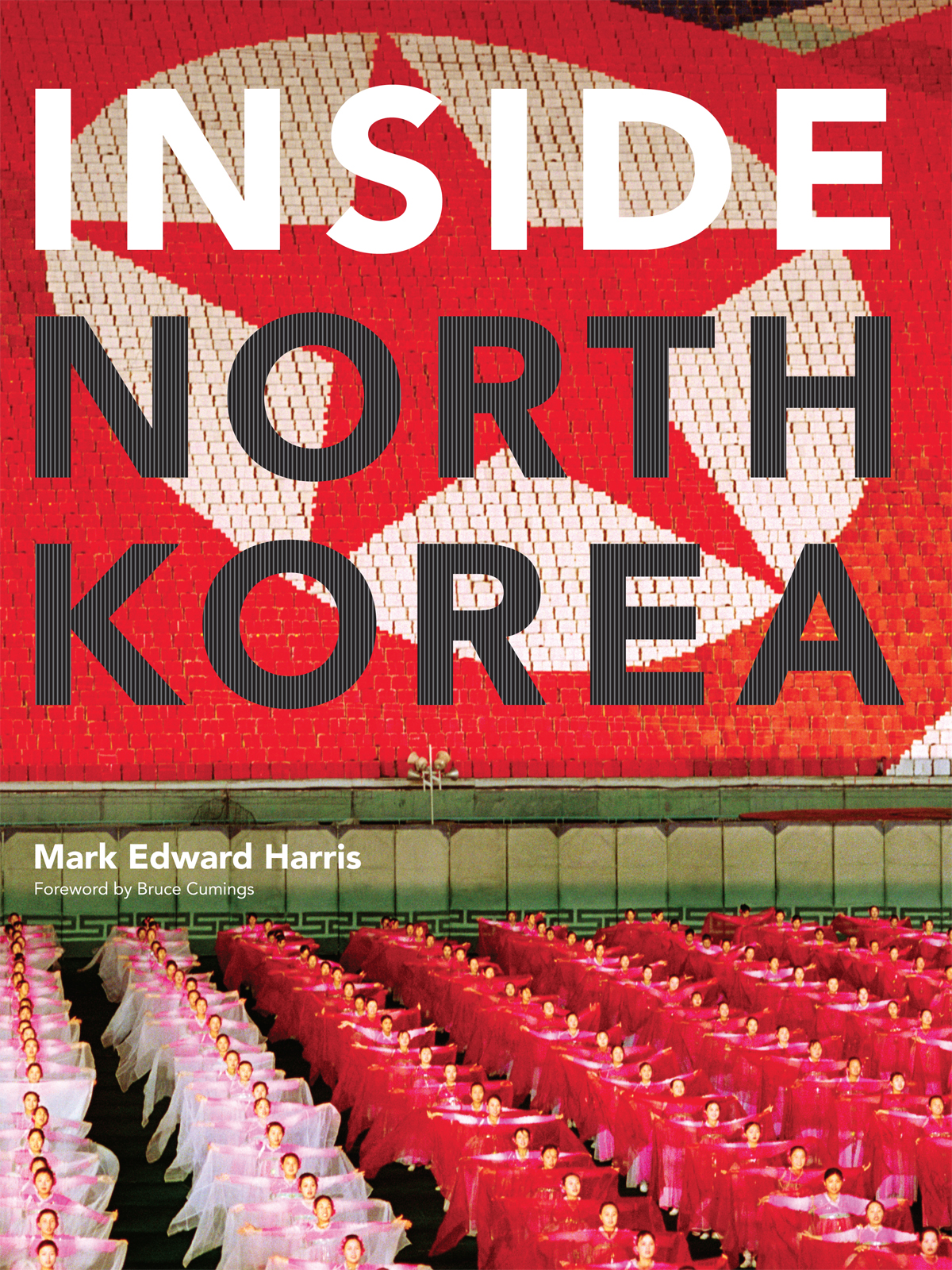

Everywhere there are the ubiquitous Great Leader and his successor son, called the Dear Leader, and a huge flock that projects an astonishing uniformity in the mass pageants the regime loves to put on, or the stadium card displays it choreographs with unparalleled skill; as Harris shows, these have now become a tourist attraction.

Everywhere, the two Kims greet you from large murals outside government buildings and schools; each room has a plaque over the door showing the dates of their visits. I visited the film studio Harris depicts, and above each door were the dates of visits by father and son. Quotations are everywhere, ranging from rip-offs of Marxist-Leninist slogans to quaint homilies reminiscent of Mr. Rogers Neighborhood. In the finely arranged Folk History Museum, next to a display of food, one can read this from Kim Il Sung: Koreans can hardly be Korean if they dont eat toenjang (a fermented bean paste, the most characteristic of Korean foods). In one photograph we see a diligent young girl playing piano. I visited a similar scene myself, with a young woman playing Korean classical music on a Japanese piano. Over her head was another slogan from Kim Il Sung: It is important to play the piano well.

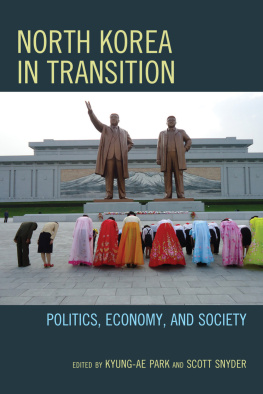

Harris shows us the largest Kim monument, a sixty-foot statue towering over the entry plaza of the Museum of the Korean Revolution. I witnessed kindergarteners assembling before it and bowing while chanting in unison, Thank you, Father. Inside the museum, the alpha and omega of the revolution is Kims life, which modern Korean history merely adumbrates. He is shown in the vanguard of a mass uprising against Japanese colonizers in 1919, when he was exactly seven years old. If it is not Kim on display, it is his son, mother, father, grand-parents, or first wife (mother of Kim Jong Il). Even his great-grandfather gets into the act, helping torch the unfortunate USS General Sherman, which ran aground just short of Pyongyang while trying to open trade with Korea in 1866. This is a communist state, but also a strange kind of communism-in-one-family.

Family bedrooms have portraits of father and son on the wall, usually with an impassive or pensive look, sometimes with a smile. Yet Kim Jong Il often has a dyspeptic, vaguely jaded look on his face. His father, always stolid Of all the slogans the traveler sees in North Korea, maybe the most poignant is the one that hangs above the main square (and can be seen in many other places): We have nothing to envy in the world. It simultaneously fits the regimes propaganda about its paradise and leads us to ask, how would any North Korean citizen know if there might be something to envy in the rest of the world? They cant even travel from the countryside to Pyongyang without a permit, and only the most reliable can travel abroad.

Mark Edward Harriss wonderful collection of photographs illustrates that North Korea does have some enviable features. When we view the awe-inspiring crater lake on White Head Mountain (Paektusan), revered as the mythical fount of the Korean people, we come to understand that one of the worlds most beautiful panoramascomparable to Mt. Fuji or Mt. Rainier, near Seattlehas been off-limits to Western tourists since 1945 because of the persistent division of this peninsula. The same was true of the Diamond Mountains (Geumgangsan), with scenery as compelling as Yosemite, until a South Korean firm got permission to bring thousands of tourists to see these mountains (and hardly anything else, of course).

Then we see a different kind of monument: a subway station with shiny walls, spic-and-span floors, and extravagant chandeliers. I once toured the subway with an eerie feeling that I was in a cathedral. Each station-sanctuary played out a theme, in lavish marble and painstakingly done inlaid tile: the harvest station, for example, shows Kim Il Sung standing amid an abundant corn harvest. The shimmering porcelain was lit by chandeliers made of glass goblets done in lime green, hot pink, and bright orange, meant to represent bunches of fruit. Then I looked at the faces of the people on the subway, some of them friendly, some of them umistakably scornful, most of them careworn and blank. We see some of them in Harriss book: nothing to envy in the world?

Everywhere there are the ubiquitous Great Leader and his successor son, called the Dear Leader, and a huge flock that projects an astonishing uniformity in the mass pageants the regime loves to put on, or the stadium card displays it choreographs with unparalleled skill; as Harris shows, these have now become a tourist attraction.

Everywhere, the two Kims greet you from large murals outside government buildings and schools; each room has a plaque over the door showing the dates of their visits. I visited the film studio Harris depicts, and above each door were the dates of visits by father and son. Quotations are everywhere, ranging from rip-offs of Marxist-Leninist slogans to quaint homilies reminiscent of Mr. Rogers Neighborhood. In the finely arranged Folk History Museum, next to a display of food, one can read this from Kim Il Sung: Koreans can hardly be Korean if they dont eat toenjang (a fermented bean paste, the most characteristic of Korean foods). In one photograph we see a diligent young girl playing piano. I visited a similar scene myself, with a young woman playing Korean classical music on a Japanese piano. Over her head was another slogan from Kim Il Sung: It is important to play the piano well.

Next page