ALSO BY BRUCE CUMINGS

The Origins of the Korean War

Volume 1: Liberation and the Emergence

of Separate Regimes, 19451947

Volume 2: The Roaring of the Cataract,

19471950

War and Television

For Ian and Benjamin

Contents

W ith this updated edition of Koreas Place in the Sun, I have sought to bring the book current, which proved fairly easy for two reasons. First, in the past decade South Korea has developed politically much along the lines that my narrative suggested, with its strong civil society and democratizing politics yielding the successive elections of two former dissidentsfirst Kim Dae Jung and then Roh Moo Hyun. Second, North Korea is stuck in the aspic of its own failure to find a new path that would enable it to meet the challenges of the twenty-first century, and after George W. Bush took office in 2001, U.S.North Korean relations returned to the pattern of confrontation and stalemate that marked the Cold War years, enabling the North to dust off its well-practiced strategies of obstinacy and recalcitrance. Thus it is difficult to say that much changed during President Bushs first administration, and the likelihood for the second is more of the samestalemate.

Only two episodes in the past decade merit extended discussion: the first is the financial crisis in 199798, which bankrupted the South Korean economy and rang the curtain down on the decades-long discourse about the Korean miracle. That high American officials were instrumental in trying to refashion the Korean model of development that they had for so longand so loudlysupported caused a spate of anti-Americanism at the time, something that was only deepened with the arrival of the Bush administration, amid a growing estrangement between Seoul and Washington over how to deal with the North. The second episode was a sincere attempt by the administration of President Bill Clinton to engage North Korea in the late 1990s, one that nearly achieved major success in 2000. Readers will find much food for thought in these two experiences, both of which departed dramatically from the general pattern of Korean history in the past six decades.

So, this version is a modest effort to bring the book up to date rather than a full revision, which can happen only after the shape and trajectory of Korea in the twenty-first century become clear. I would like to thank Steve Forman and Sarah England of W. W. Norton for suggesting that an updating would be appropriate, and for seeing this version through to publication. Professor Elaine Kim of the University of California at Berkeley was also kind enough to dun the publisher about bringing the book current. Writing now in this new century, I remain amazed and humble before the turbulence and complexities of Koreas modern history. that an updating would be appropriate, and for seeing this version through to publication. Professor Elaine Kim of the University of California at Berkeley was also kind enough to dun the publisher about bringing the book current. Writing now in this new century, I remain amazed and humble before the turbulence and complexities of Koreas modern history.

T he idea for this book germinated when John W. Boyer, dean of the college at the University of Chicago, provided me with some summer money to prepare a reader on Korea for the colleges justly respected civilization program. Some years later when I told hima historian of Germany and Austriamy book title, he could not suppress a laugh: it seemed a bit Bismarckian. The Greek word asu and the Latin word oriens connoted rising sun or the east, and for centuries everything east of Istanbul signified lands of the rising sun, just as occidens conjured the territory of the setting sun; Martin Luther identified Europe with the Abend (or evening) land, the Orient with the Morgen (morning) land. Now only Japan claims to be a land of the rising sun, and only anxious Americans identify their country with the setting sun. The world that has given us rises and falls and periodic eclipses is not that of Greece and Rome, however, but the industrial epoch, with its relative handful of advanced industrial states and their incessant competition. It is that solar system that Korea has now joined (and that is all I mean by the title).

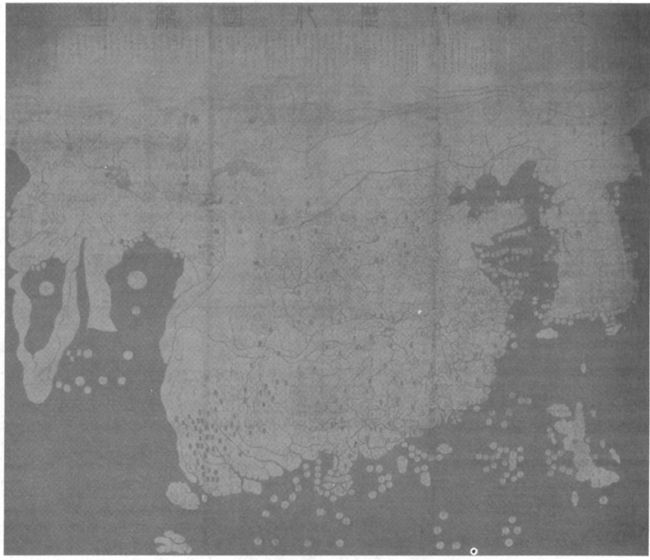

To the left is the kangnido, a map of the known world drawn by Korean cartographers in 1402, nearly a century before the Western voyages to the Americas. Korea, the Eastern country, hangs like a large grapefruit next to China, into which is collapsed India and South Asia. The Japanese islands are insignificant, placed down near the Philippines. This map may be old, but it tells us what Koreans think about their country and always have: an important, advanced, significant country, which may have been a shrimp among whales during the imperial era, a small country jammed cheek-by-jowl against great powers during the Cold War, a poor and divided country after the Korean War, but now is a nation reoccupying its appropriate position in the world.

Korea is roughly the size of England, with a population in both Koreas approximating that of unified Germany. If it were not a peninsular promontory of China, we would not think of it as a small country (no one thinks of Japan or England as a small country). Many Americans also believe Korea is remote or far-off; for different reasons the Japanese enjoy referring to North Korea as the remotest country. Northeast Asia is remote only from the Eurocentric and civilizational standpoint of the Westsomething much prized these days because it is much threatened. Many Westerners still believe that European civilization has had some unique historical advantage, some special quality of race or culture or environment or mind or spirit, which gives this human community a permanent superiority over all other communities, at all times in history and down to the present. We will find that Koreans think about the same thing, except they replace Europe with their own countryor, historically, China. Beijing sits in the middle of the kangnido because it was the seat of known civilization.

What is meant by modem Korea? When other countries start acting a bit like Western ones, we often say they modernize. Today we have many such countries, but according to some recent accounts noneincluding the economic giant Japanknow true freedom as do the nations of Europe. Somehow this prize at the end of the modernizing rainbow remains elusive. The twentieth century was so full of stunning events, however, running the full spectrum from the great and wonderful to the horrible and unimaginable, that we can no longer use the term modern as a sign of tribute, or progress as a sign of approbation. Modern has meant that people work in industrial settings, use advanced technology as a tool, live in cities or suburbs, enjoy or suffer the attentions of the most industrially advanced nations, and experience a democratic or an authoritarian politics rather different from previous political forms. The twentieth century was one of industrialization and technological change, the world-ranging power of those nations having both and putting both to good military use, and the full emergence of masses of the population as political participants. The modern is not a sign of superiority but a mark, a point, on a rising and falling scale. Korea began the twentieth century near the bottom of that scale and begins the twenty-first near the top. Along the way there have been many gains and many losses, and a remarkable story of human triumph over adversity. But we now have a modern Korea.

Next page