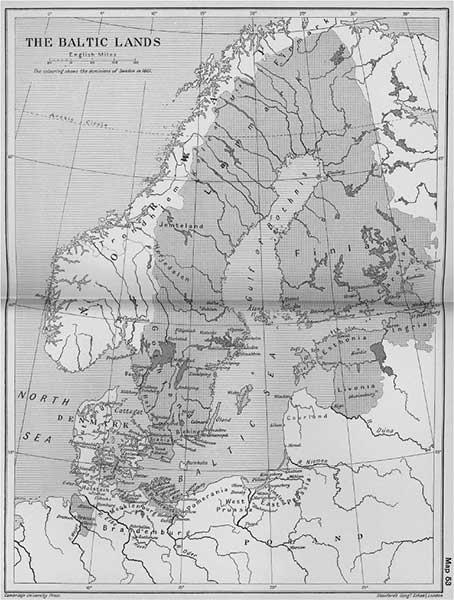

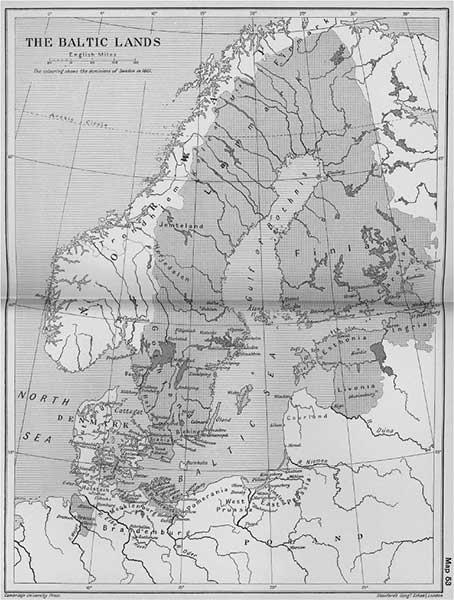

The Baltic in 1661, during the time of Swedens domination of the region. Although the Gulf of Finland is unnamed, at its eastern end, the map already shows St Petersburg, which was not in fact founded for over another four decades.

First published 2019

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

Copyright Caroline Boggis-Rolfe, 2019

The right of Caroline Boggis-Rolfe to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781445688503 (HARDBACK)

ISBN 9781445688510 (eBOOK)

Map and table design by Thomas Bohm, User design.

Typesetting and Origination by Amberley Publishing.

Printed in the UK.

Contents

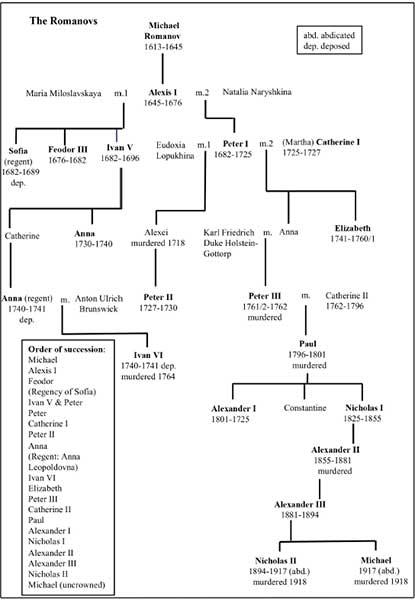

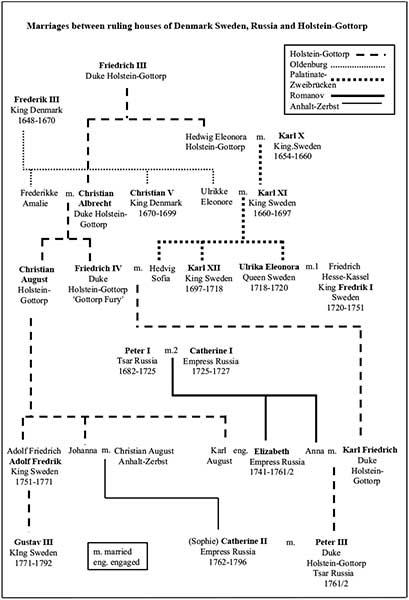

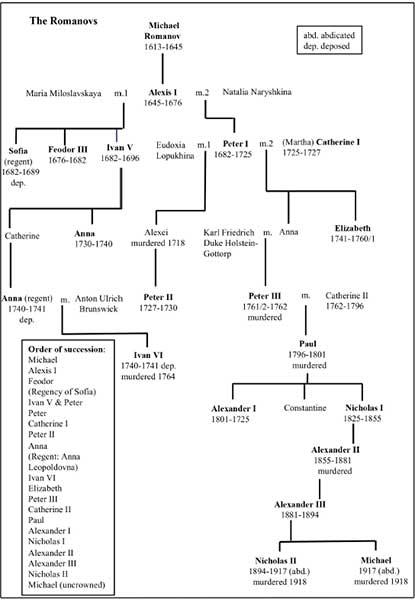

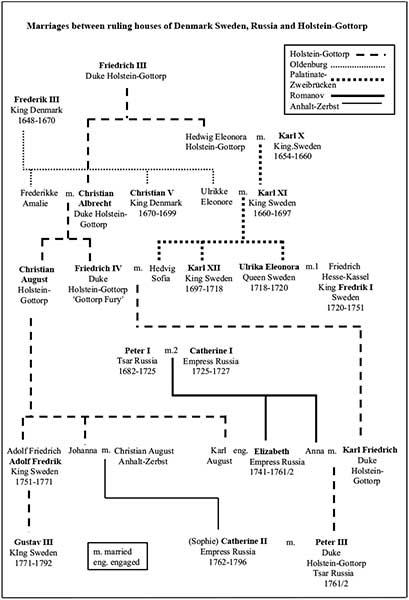

Principal Family Trees

Introduction

The Three Sisters, the typical fourteenth-century merchant houses in Tallinns lower town.

My interest in the Baltic has developed over the many years that I have been visiting the region, but while I was lecturing on the subject, I discovered the shortage of mainstream studies of the area available to English speakers. I have therefore set out to produce something that fills that gap, giving an overview of its history through the lives of the people who shaped it. As the individual states around the Baltic have interlocking stories, I feel that to understand the narrative of one place it greatly helps to have a knowledge of the others. Loosely speaking the Hanseatic League was a leading presence by the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and Denmark by the fifteenth and sixteenth. Meanwhile, the vast, recently united Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had also risen to prominence, and it now held sway in the Baltics more south-easterly parts. But during the early 1600s Sweden would start to overtake its rivals, and soon be the dominant power throughout the whole area, holding onto its position until challenged and ultimately defeated by Russia at the start of the eighteenth century. All this time, however, Prussia, too, had been growing in significance, so that by the mid-1700s it had in its turn become a key player in the affairs of the region, a role that it would maintain until the start of the Napoleonic Wars. Although it then suffered some crushing setbacks, it would eventually recover and become the major player in the newly formed German Reich , its king rising to be the first hereditary emperor or kaiser . Finally, during the course of the long and turbulent twentieth century, the other smaller states around the region would achieve their independence, at last separating themselves from the powers that had dominated them for hundreds of years. The Baltic was not just an area of local interest, as from early days its affairs had held commercial significance for places further afield, with the French, the Dutch, the British, and even to a certain extent the Austrian Habsburgs paying ever closer attention to events in this part of the world.

Today when cruising through the Baltic in a modern ship it can be hard to imagine the innumerable tumultuous events that have occurred in these waters over the centuries. Although during the summer months this sea is often deceptively calm, its surface literally smooth as glass, on other occasions it takes on a totally different character. From time to time the area is hit by such violent storms that in certain places waves can reach up to around 8 metres, with the odd individual one greatly exceeding even that. In addition, destructive storm surges can strike the shores, brought on by the combination of strong winds, shallow waters, and the changing sea levels the latter caused by melting ice or rivers in flood. From earliest times the archives have recorded the many disasters occurring in this region, such as that of 1872 when the frequently battered German town of Warnemunde was so badly hit that many people were left homeless or dead. Most recently, in 2017 serious flooding struck all along the north German coast between Kiel and the Polish border, causing damage to Lbeck, Rostock, Wismar and many other places. Similarly, St Petersburg, situated in the low-lying delta of the River Neva, has until recently faced repeated inundation beneath the surges that from time to time sweep up the Gulf of Finland, a situation now apparently resolved by the recently constructed flood barrier at Kronstadt. And for those living in the more northerly parts of the Baltic in particular the furthest reaches of the Gulf of Bothnia just some 50 miles or so from the Arctic Circle life is additionally complicated by the high latitudes with their long nights and freezing temperatures in winter, when the sea can, even in todays changing climate, be shrouded in a mantle of ice that cuts off most maritime communication. At such times in the past the only alternative for the local people was to make their way across the frozen water, a perilous route also used on occasion by invading armies.

Even while bearing all this in mind, for the summer tourist travelling in comfort today it is often difficult to identify with the experiences undergone by the intrepid pioneers, tradesmen and others of earlier times, people who would so often find themselves struggling against winds and waves and other equally unpredictable challenges. From the Vikings to the Hansa merchants, men would set out through the uncharted and often pirate-infested waters, the former probably seeking booty if not new lands, the latter in search of fish and other commodities. After them came the very possibly scared or sick sailors and soldiers, many of the latter no doubt at sea for the first time, who had to spend weeks in their tossing ships making their way towards the next bloody land or sea battle. And contemporary accounts also tell us of the apprehensive young brides, who all too often began their daunting exile battered for days by stormy conditions that left them in fear of their lives. A graveyard of ships attesting to these stories now lies on the seabed.

Although the Baltic is relatively small when viewed in world terms, it is nonetheless the home of a variety of peoples of different ethnic descent, speaking more or less ten major languages, not to mention several other dialects. Despite the attempts of the Soviet Union to wipe out or alter the local cultures in their Baltic states, these have been revitalised since their independence. Poland, with its constitutional government, now enjoys the freedom to revisit its past and express its individuality unhindered. And then, leaving aside the question of the northern Sami people, the Scandinavians, whose nations have for so long been brought together in various unions, still proclaim their differences in language and character. But despite this intentional separation in cultural terms, there has always been a connection between the regions, on the positive side represented by an exchange of goods, ideas, and peoples, on the negative by the multiple local conflicts and rivalries. It is this dichotomy that we shall now explore, examining the two sides of the Baltic, on one hand a crucible of different cultures, but on the other a circumscribed, close-knit community with the usual tensions and disputes that are found among families and near neighbours.

Next page