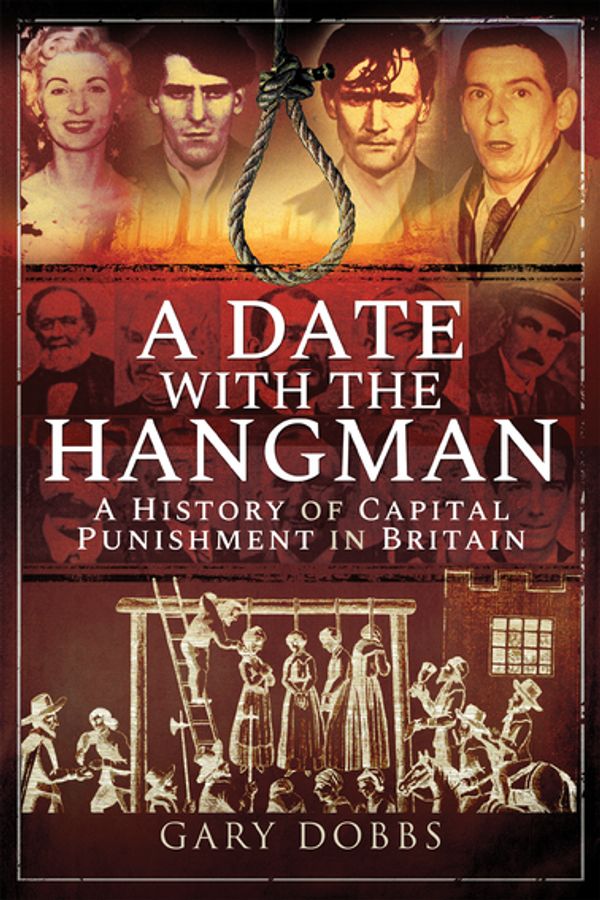

A Date with the Hangman

A Date with the Hangman

A History of Capital Punishment in Britain

Gary Dobbs

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

Pen & Sword History

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Gary Dobbs, 2019

Hardback ISBN 978 1 52674 743 3

Paperback ISBN 978 1 52676 740 0

eISBN 978 1 52674 744 0

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52674 745 7

The right of Gary Dobbs to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Books Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Executions are so much a part of British history that it is almost impossible for many excellent people to think of a future without them.

Samuel John Hoare, In the Shadow of the Gallows (1951)

Introduction

I t is a sobering thought that until the closing years of the twentieth century, Britains courts were technically able to impose the death penalty for a number of offences; both civil and military. And although the last judicial hangings took place in 1964, the death penalty, in theory at least, remained for a number of offences. It would not be completely abolished until 1998, and even then it wasnt until 2004, when the European Convention on Human Rights became binding on the United Kingdom, that the slim possibility that capital punishment could be restored was removed.

Although the main focus of this book is a study of British judicial hangings during the twentieth century, in which all 865 executions carried out between the years 1900 and 1964 are detailed, it is important to consider this overall history of the death penalty as it relates to the judiciary. And so, to truly understand capital punishment and its eventual abolishment, one must go beyond judicial sentencing and look at the whole picture; the origins of why hanging became the preferred method of punishment for the most heinous of crimes.

It is thought that hanging as a capital punishment was first brought to Britain in the latter half of the fifth century by the Anglo Saxons, but throughout history people have been burned at the stake, had the skin flayed from their bodies, been beheaded, garrotted, hung, drawn and quartered, stoned, disembowelled, buried alive, all under the guidance of a vengeful law, or at least what passed for law at any given period.

However, with the arrival of the Germanic Anglo-Saxon tribes, hanging at the gallows became the principle form of judicial execution. The gallows were an important element of Germanic culture. Indeed, the legendary brothers Hengist and Horsa, whom history records as leading the invasion of Britain in the fifth century, used a very rough version of a gallows for hanging. It is from here that the accepted method of hanging developed.

In 1066 when William the Conqueror became the first Norman King of England, he decreed that hanging should be replaced by castration and blinding for all but the crimes of poaching royal deer. Hanging would later be reintroduced by Henry I as a means of execution for a larger number of offences, although during this period in history other methods of execution such as beheading, burning at the stake and being boiled alive were also used. In fact it wasnt until the eighteenth century that hanging had become the principle punishment for capital crimes in the United Kingdom.

The eighteenth century would also see the start of the movement to abolish capital punishment, and in 1770 the politician William Meredith suggested that more proportionate punishments for crimes be introduced. He was joined in the early nineteenth century by the legal reformer and Solicitor General Samuel Romilly, and the Scottish jurist, politician and historian James Mackintosh, both of whom introduced bills into Parliament in attempts to de-capitalise minor crimes. At this time there were more than 200 crimes defined in law as capital offences; among these were impersonating a Chelsea pensioner, being found in a forest while disguised, and damaging Westminster Bridge. During this period the law did not distinguish between adults and children, and it was not uncommon for children as young as 7 to be sent to the gallows. It would not be until 1861, with the Criminal Law Consolidation Act, that the number of capital crimes was reduced to just four, these being murder, arson in a royal dockyard, treason and piracy with violence.

A hundred years later, Britain would finally take steps to end capital punishment with the last judicial executions taking place in August 1964, when both Peter Anthony Allen and Gwynne Owen Evans were executed for the joint murder of John Alan West. These men were executed at separate prisons at precisely 8am on 13 August. There was little outcry, few headlines and yet these two men would go down in history as the last men to face the hangmen in the United Kingdom.

Chapter One

Beheading: Punishment and the Nobility

A lthough the Celts, regarded by many historians as being the first inhabitants of the British Isles, had a long tradition of beheading, the first recorded judicial execution did not take place until the third century AD. This was during the Roman occupation; indeed, the Romans regarded beheading as the only humane form of execution. It was seen as being the least painful way of putting someone to death, and in most cases was reserved for the nobility and seldom used on common criminals. Mark Anthonys grandfather and son were executed in this way, as was the famous statesman Cicero.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles tell us that the first judicial beheading to be properly recorded took place in AD 283, although experts debate the actual date with opinion placing the event sometime between AD 209 and 313. During this period Christianity was being suppressed by the Roman rulers and a persecuted Christian priest named Amphibalus took refuge with a young man named Alban. This was in the city of Verulamium, situated to the south-west of modern-day St. Albans, and in order for the priest to evade capture, Alban exchanged clothes with the man. This resulted in Alban being seized and executed in place of the priest. He was beheaded with a sword on the site that would later house St. Albans Abbey. There are many differing accounts of the execution, most written hundreds of years after the fact. One report, written by the Benedictine monk, Bede, states that Albans head rolled down a small hill, and where it stopped a well suddenly sprung up from the ground. References to this spontaneous well are recorded in local place names such as Halywell, which in Middle English would mean Holy Well. The hill leading to where the abbey now stands is called Holywell Hill, but it has been called Halliwell Street and other variations since at least the thirteenth century.