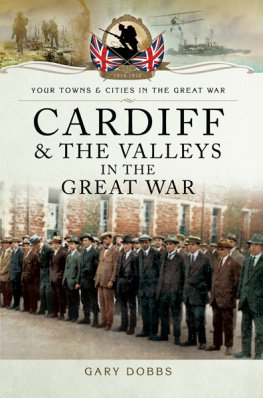

This book is dedicated, with the greatest respect,

to all those who serve past, present and future.

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Gary M. Dobbs, 2015

ISBN 978 1 78346 355 8

eISBN 9781473857766

The right of Gary M. Dobbs to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Acknowledgements

I am deeply in the debt of Gilly Smith for all her help regarding information about her grandfather, Herbert Paine Smith, who served with the 11th Welsh Battalion, the Cardiff Pals. In 1981 Gillys father, Major Bob Smith, sat down with Herbert in order to record his memories of the Great War. These recordings provided me with invaluable first-hand information on the Cardiff Pals.

I also found the book, Cardiff Pals by K. Cooper and J.E. Davies (Militaria Cymraeg, 1988) to be a great source of information on the day-to-day life of those serving in the battalion. Thanks go too, to the staff at Cardiff Central Library without their expertise and service this book would have been a far more difficult project. I also owe thanks to the archives of The South Wales Echo, Pontypridd Observer and Western Mail .

Huge thanks are due to Roni Wilkinson of Pen and Sword for holding my hand throughout this project, and Jen Newby whose careful editing greatly improved my work. Finally, I would like to acknowledge Lisa for all the help, especially in providing a never-ending supply of coffee.

Photographic Credits

Many of the photographs used throughout this book are in the public domain. However, I am grateful to The South Wales Echo and Media Wales for granting me permission to use images from their collections within this book.

The author took most of the war memorial photographs in .

Introduction

Looking back, with the full weight of history at our fingertips, it would seem that the First World War was inevitable. It may have taken an assassination in Sarajevo during a June afternoon in 1914 to finally tip the world over the edge and into the abyss, but for months, if not years prior to the event the dark clouds of war had been forming.

The gathering together of gigantic forces could be felt across Europe as the world approached a truly terrible period in human history. Initially known as the European War, the conflict would eventually draw in all of the worlds great economic powers and result in shattering casualty statistics. Even today, after other terrible conflicts have been consigned to history, these statistics still seem incredible. In the end, more than 70 million military personnel were involved in what would become the biggest war in history. Nine million combatants would lose their lives, as the War employed new technology able to deliver devastation on a previously unthinkable scale.

For a world accustomed to brief, quickly resolved wars, often won and lost in a single battle, the Great War would come as a surprise. Not only would the war be fought on land and at sea, but it also took place in the air. Brutal new weapons would be used: machine guns, tanks, flamethrowers and, perhaps most terrible of all, poison gas.

By early August 1914 it was clear that Britain had no option but to enter the war. The complicated web of political allegiances across Europe meant that Britain, then Europes greatest superpower, could not stand back while the rest of the continent imploded. Even so, only two days before Britain declared war on Germany, the British Government and the most of the population were more inclined to remain neutral in the impending European crisis. Had Germany refrained from invading Belgium a nation that Britain had sworn to protect in the 1839 Treaty of London then the United Kingdom may not have become embroiled in the conflict.

A diplomatic crisis was sparked off by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungry, by Yugoslav nationalist Gavrilo Princip, while the Archduke was on an official visit to Bosnia. Austria-Hungary, blaming Serbian nationalists for the murder, declared war on Serbia. In preparation for the invasion of Serbia, the Austro-Hungarians fired the first shots on 28 July 1914; this triggered a catastrophe which eventually sucked in all of the major world players.

Russia was forced into the crisis because it had sworn to protect Serbia. This led Germany, then aligned with Austria, to issue a warning that if Russia came out in defence of Serbia, the German Government would, in turn, declare war on Russia. During this period Germany was a relatively new country on the world stage, having only recently been formed by the amalgamation of the Prussian states, and the thought of being surrounded by warring nations terrified the German Government.

When the British ultimatum regarding Belgium was ignored by the Germans, Britain declared war on Germany at midnight on 4 August 1914. In the meantime the German invasion of neutral Belgium and Luxembourg spread into France. After the Allied Forces eventually halted the German advance on Paris, a stalemate was quickly reached and a static front line known as the Western Front opened up. The war in Europe became a war of attrition, with a front line that would change very little until 1917.

While trench warfare has provided the most abiding images of the Great War, along with the phrase, Over the top, this is a restricted view of the conflict. Today we might imagine a war measured in yards of mud along a small area of France, when, in reality, theatres of war also opened up in Italy, Africa, Asia and Turkey. An exclusive focus on the Western Front also ignores the war that was being fought at sea and, for the first time, in the air. The War was fought in many different ways too; not only in the various theatres of war were sacrifices being made and great bravery displayed. In a sense, this war was also fought on the Home Front and those who stayed in Britain faced struggles that were significant, if not comparable with those endured by soldiers on the battlefield.

On the outbreak of war Cardiff was one of the richest trading centres in the world, and had recently been granted city status in 1905. The citys wealth came from the coal often referred to as black gold mined in its surrounding valleys, which was exported around the world. It was in Cardiff, at the Coal Exchange on Mount Stuart Square, that Britains first million pound deal was struck in 1907.

Next page