A CULTURAL HISTORY

OF MONEY

VOLUME 1

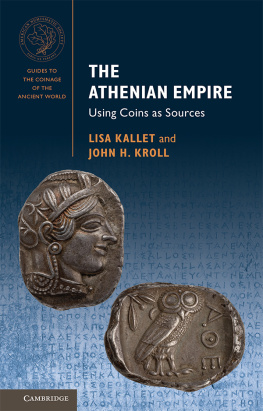

A Cultural History of Money

General Editor: Bill Maurer

Volume 1

A Cultural History of Money in Antiquity

Edited by Stefan Krmnicek

Volume 2

A Cultural History of Money in the Medieval Age

Edited by Rory Naismith

Volume 3

A Cultural History of Money in the Renaissance

Edited by Stephen Deng

Volume 4

A Cultural History of Money in the Age of Enlightenment

Edited by Christine Desan

Volume 5

A Cultural History of Money in the Age of Empire

Edited by Federico Neiburg and Nigel Dodd

Volume 6

A Cultural History of Money in the Modern Age

Edited by Taylor C. Nelms and David Pedersen

A CULTURAL HISTORY

OF MONEY

IN

ANTIQUITY

Edited by Stefan Krmnicek

CONTENTS

Stefan Krmnicek

Andrea Casoli and Marc Philipp Wahl

Franois de Callata

Stefan Krmnicek

Stphane Martin

Nathan T. Elkins

Alicia Jimnez

Clare Rowan

INTRODUCTION

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

CHAPTER 1

.

.

.

.

.

.

CHAPTER 2

.

.

.

.

CHAPTER 3

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

CHAPTER 4

.

.

.

.

.

CHAPTER 5

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

CHAPTER 7

.

.

.

.

.

.

TABLES

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 2

.

.

.

Franois de Callata is Head of Department at the Royal Library of Belgium, Professor at the Free University of Brussels and Directeur dtudes at the cole Pratique des Hautes tudes (Paris-Sorbonne). He has published extensively on Greek numismatics, the ancient economy, and history of research. His latest books include Quantifying the Greco-Roman Economy and Beyond (2014) and Cloptre, usages et msusages de son image (2015).

Andrea Casoli is Research Associate at the State Collection of Coins and Medals of the Canton of Ticino (Switzerland) and researches primarily Roman numismatics and Ancient to Medieval coin finds. He is currently writing a monograph on the Imperial coinage of Emperor Nero.

Nathan T. Elkins is Associate Professor of Art History at Baylor University. His research areas and expertise include Roman art and archaeology, coinage and coin iconography, topography, and architecture. His publications include Monuments in Miniature: Architecture on Roman Coinage (2015) and The Image of Political Power in the Reign of Nerva, A.D. 9698 (2017).

Alicia Jimnez is Assistant Professor at Duke University. Her research focuses on the study of Roman expansion in the western Mediterranean, Roman colonialism, cultural change, and monetization in Hispania. She is author of Imagines Hibridae. Una aproximacin postcolonialista al estudio de las necrpolis de la Btica (2008) and editor (with M. P. Garca-Bellido et al.) of Barter, Money and Coinage in the Ancient Mediterranean (2011).

Stefan Krmnicek is Junior Professor of Ancient Numismatics at the University of Tbingen. He has published on many aspects of Roman archaeology, with a special interest in questions of ancient coin use, economic history, and coin and (with M. Flecker et al.) Augustus ist totLang lebe der Kaiser! (2017).

Stphane Martin is Postdoctoral Associate Researcher at HeRMA, EA 3811 of the University of Poitiers. His research interests lie in the intersection of Roman archaeology, the ancient economy, and Celtic and Roman numismatics. He is author of Du statre au sesterce. Monnaie et romanisation en Gaule du Nord et de lEst (2015).

Clare Rowan is Associate Professor in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick and primarily researches on how ancient coinage was used as a medium for the negotiation of power and the expression of identity. She is author of Under Divine Auspices: Divine Ideology and the Visualisation of Imperial Power in the Severan Period (2014) and (with A. Bokern) Embodying Value: The Transformation of Objects in and from the Ancient World (2014).

Marc Philipp Wahl is Assistant Curator at the Martin von Wagner Museum of the University of Wrzburg. He completed his Ph.D. in Numismatics at the University of Vienna in 2017. His latest project is concerned with the iconography of Greek coins in Classical times and the digitization of the coin collection of the Martin von Wagner Museum.

When the British Museum decided in 2012 to redesign Room 68, the hall containing objects from its Department of Coins and Medals, its curators made a bold departure from how numismatic material had conventionally been displayed. Rather than cases filled with row upon row of gold, silver, and bronze coins of European antiquity, the new gallery design featured all manner of objects, not limited to coin or paper currency, capturing the history of transactional artifacts and infrastructures from shells to mobile phones. Each case had a theme: cases on one side of the gallery spotlighted moneys institutional supports and issuing authorities, while cases on the other underscored all the myriad ways people use money, not just for exchange or payment but for ritual or religious observance, political contestation, adornment, and storytelling.

The intention in preparing these six volumes was to provide readers with a similar experience, inviting them into the wonder-cabinets of money in all its variegation, multiplicity, and complexity. What emerges is moneys irreducible plurality, the multiple stories it tells. Money opens windows into plural economic and moral worlds, too, worlds of value and evaluation, wealth and worth. Never merely coin, cash, or credit rendered in strictly economic terms, money is so much more than the old couplet would have it: Money is a matter of functions four: a medium, a measure, a standard, a store. Instead, money is always also a medium of communication, a set of instruments with which people exchange messages with one anotherabout price, to be sure, but also about political conviction and authority, fealty, desire, or disdain. And money is a method of memorializing the past so that relations established among people, institutions, the gods, and the ancestors can be carried forward through the present and into near, distant, and imaginary futures.

Money is in this sense both irredeemably cultural and historical, and so it is apt that this six-volume Cultural History of Money should spotlight moneys relation to religion, technology, the arts and literature, everyday life, metaphysical interpretation, and a wide variety of issues of the age. While many contributors to the first several volumes are numismatists and archaeologists, trucking in the material evidence of coin and bullion, the volumes also contain contributions from scholars of digital infrastructures, literary and legal historians and science fiction scholars, sociologists and anthropologists, economists and artists.

Archaeologists have long bemoaned the fact that the great majority of ancient coins in museums and private collections today were unearthed without any data having been collected on their surrounding context, rendering much of the ancient and even more recent past a mystery. Even where the context for a particular find is present, its interpretation is always ambiguous. In the contemporary period, money is surrounded by contextcables and wireless signals, data protocols and computer servers, lobbying groups and legislators voluminous writings, television soap operas and online social media. Yet just as with ancient hoards, we have difficult escaping our own assumptions about what money is, what people do with it, and the style with which they do so.