Water Politics in Northern Nevada

SECOND EDITION

WILBUR S. SHEPPERSON SERIES IN NEVADA HISTORY

WILBUR S. SHEPPERSON SERIES IN NEVADA HISTORY

Series Editor: Michael S. Green

University of Nevada Press, Reno, Nevada 89557 USA

Copyright 2014 by University of Nevada Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Design by Kathleen Szawiola

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wilds, Leah J.

Water politics in northern Nevada : a century of struggle /

Leah J. Wilds. Second edition.

pages cm. (Wilbur S. Shepperson series in Nevada history)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87417-951-4 (paperback : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-0-87417-952-1 (e-book)

1. Water-supplyPolitical aspectsNevadaHistory. 2. Water resources developmentPolitical aspectsNevadaHistory. 3. Water reusePolitical aspectsNevadaHistory. 4. Newlands Project (U.S.)History. 5. Truckee River (Calif. and Nev.)Environmental conditions. 6. Carson River (Nev.)Environmental conditions. 7. Environmental policyNevadaHistory. 8. NevadaPolitics and government. 9. Social conflictNevadaHistory. 10. NevadaSocial conditions. I. Title.

TD224.N2W55 2014

333.91'6209793dc23 2014020822

This book is dedicated to

the love of my life, Robert Dickens,

and to the light of my life,

Viki Wilds

Illustrations

PHOTOGRAPHS

MAP

Preface

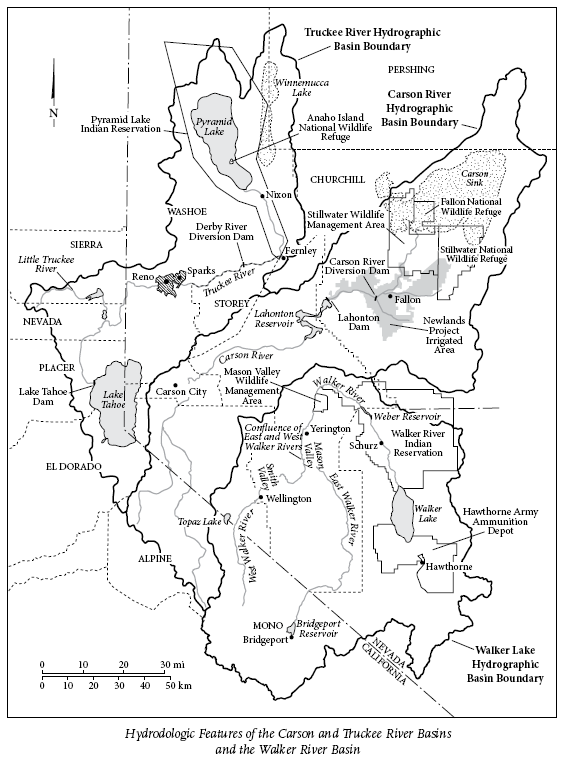

This book is a political history of conflict over water resources in northwestern Nevada and an analysis of regional approaches to resolving those conflicts. The waters discussed are conveyed by the Truckee, Carson, and Walker River systems. The use, allocation, and ownership of these waters have long been the subject of legislation and litigation.

The first edition of Water Politics in Northern Nevada, published in 2010, dealt with water policy and legislation concerning the Truckee and Carson River water systems. This revised edition brings the reader up-to-date on the implementation of the 2008 Truckee River Operating Agreement (TROA), including ongoing efforts to preserve and enhance Pyramid Lake. The second edition now also includes a discussion of the Walker River Basin, following a major project undertaken to address concerns about the health and viability of Walker Lake. The approaches taken to save these two desert treasures are offered as models for resolving similar water resource conflicts in the West.

The audience for this book includes scholars and students interested in water politics, contemporary environmentalists, new residents to the West, and those interested in regional and local natural resource history. Every effort was made to make this book accessible and interesting to both an academic and a lay audience.

Many people contributed to the writing of this book. I would like to thank all of the individuals who made themselves available for interviews. I would like to thank Chester Buchanan for helping me better understand the role of US Fish and Wildlife in the water acquisitions process and David H. Levin for his excellent editorial skills. I am indebted to Donald B. Seney, emeritus professor of government at the University of California and consultant to the US Bureau of Reclamation, who gave me access to the wonderful oral history he collected about the Newlands Project. Support for the research and writing of the second part of this book came from the Walker Basin Project. I would like to thank all of those who were involved in that project, especially the scientists who conducted research in the Walker Basin. And finally I would like to give an especially warm thank-you to Senator Harry Reid, without whom none of what is detailed in this book could have been accomplished.

Introduction

Contemporary conflict over the use of the waters of the Truckee and Carson Rivers was largely the result of the Newlands Project, the first reclamation project undertaken by the Bureau of Reclamation. Completed in 1915, the Newlands Project vision was simple: capture and store the combined waters of the Truckee and Carson Rivers to irrigate nearly a half-million acres of land, primarily in Washoe and Churchill Counties. Although the project never irrigated more than 73,000 acres, an average of 406,000 acre-feet (a-f) of water was diverted to project lands for decades.

The natural terminus of the Truckee River is Pyramid Lake, a desert terminus lake on the Pyramid Lake Paiute Reservation. The lake is home to the remains of a Lahontan cutthroat trout (LCT) population. It is also home to the unique and prehistoric cui-ui fish, which are found only in Pyramid Lake. These fish were declared threatened and endangered, respectively, under the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966. Not only did the decrease in flows over the years threaten the fish and their ability to spawn, but the decreased volume of water in the lake, combined with higher salinity levels, also threatened the lake's ability to support any aquatic life.

Beginning in the 1960s, the Pyramid Lake Tribe began to challenge the right of Newlands Project users to continue to consume that much water. Other usersenvironmental, urban, Native Americanengaged in numerous legal battles over who had the right to use how much water from the Carson and Truckee Rivers and toward what ends. The fact that both rivers are shared by California and Nevada only exacerbated those conflicts.

Beginning in the 1980s, the federal government, itself involved in many of these lawsuits, encouraged the parties to enter negotiations to overcome their differences. Sponsored by Senator Harry Reid, the settlement that was reached was incorporated into Public Law (PL) 101-618, passed by Congress in 1990. Since that time, efforts have been made to implement its many provisions. One of those provisions required additional negotiations to create a new set of operating criteria for the Truckee River. The end result has been a much more flexible operating system for the river, enabling competing users to have most of their water needs met most of the time. That effort took more than seventeen years, ending with the signing of the Truckee River Operating Agreement on September 6, 2008. All of the provisions of PL 101-618 are not yet fully implemented. Until they are, the provisions of that law will not become fully effective. Efforts are under way to make this happen.

The Walker River system presents, in some sense, a more complex water resource allocation and use situation. Unlike the Truckee and Carson, the Walker does not involve the federal presence of the US Bureau of Reclamation. Water storage and diversion infrastructure features were privately funded and constructed. Management is provided by a private irrigation district. The natural terminus of the Walker River is Walker Lake. As irrigated agriculture became a dominant aspect of the economy in the Walker Basin, more and more Walker River water was captured and stored in two reservoirs to be delivered to irrigated lands. By 1925 96,000 irrigated acres were in production in the Walker Basin. By the middle of the twentieth century, the lake level had dropped 145 feet. By 2007 it dropped another 4 feet. Resulting changes in water qualitydue in large part to increased salinity levelsthreatened the aquatic life dependent on the lake as well as the sustainability of the lake itself.

As was the case with the Truckee and Carson Rivers, increased competition over the use of Walker River water has resulted in decades of litigation between agricultural, Native American, and environmental interests. A 1993 court-ordered mediation to settle their differences out of court resulted in stalemate. The parties resumed litigation.