2021 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045 ), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dickson, John S. (John Shields), author.

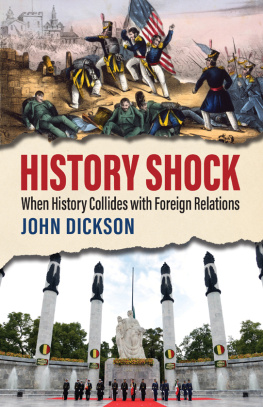

Title: History shock : when history collides with foreign relations / John Dickson.

Other titles: When history collides with foreign relations

Description: Lawrence : University Press of Kansas, 2021 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020040365

ISBN 9780700632022 (cloth)

ISBN 9780700632039 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Dickson, John S. (John Shields) | United States. Foreign ServiceOfficials and employeesBiography. | DiplomatsUnited StatesBiography. | United StatesForeign relations1989 | United StatesForeign relations. | Diplomatic and consular serviceUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Diplomatic and consular serviceUnited StatesHistory21st century.

Classification: LCC E840.8.D477 A3 2021 | DDC 327.2092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020040365.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in the print publication is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials

Z 39.48 - 1992 .

Preface and Acknowledgments

O ne of the reasons I look back fondly on a career in the Foreign Service was that it afforded me an unending opportunity to learn. The sense of wonder upon arriving in a foreign culture and taking in the new and different sights, sounds, and smells always invigorated me. After three days, I found myself an expert, only to spend the next couple of years peeling back the layers of complexity and nuance in each foreign environment. The realization would emerge that I could never truly become an expert, but the ability to keep learning lasted until the day I left, making for rich, fulfilling, and intense experiences.

For these reasons, international travel continues to take up too much of my annual calendar and budget, but there are always more places than either time or money will permit. I used to refer to getting bitten by the international bug that wont let go and will return once the pandemic eases.

Early on, I found that in the process of learning about the foreign culture, I was also gaining insight into my own. Sometimes this happened as I interacted with people whose views about the United States ranged from the comical to the infuriating. One university professor in South Africa, for example, wanted to know why he couldnt vote in US elections since our decisions would impact his own life. Conspiracies about the role of the United States in seemingly every single mishap or views gleaned from the American television shows seeped into foreign perceptions of home.

Seeing different ways of life also made me look at the environment I grew up in and took for granted. Like the fish who doesnt understand water until forced out of it, I was able to see those areas that the United States had in common with or where we stood apart from other societies. These ranged from the mundane, such as the hours for work or meals and the high walls surrounding our homes, to the more profound, including the decidedly more visible complexity of race relations and tensions in the United States. I suspect I am not alone in this aspect of foreign travel or living. Not only do we learn the foreign culture, but the opportunity to take in that environment causes us to learn and for the most part appreciate our home culture.

Over the course of my career, I began to notice a history gap: my foreign counterparts were drawing on a history that I never learned, either because I had a competing version or because I was simply unaware of any version at all. Even though I had studied history in college and continued to read almost exclusively nonfiction histories and biographies, I grew increasingly aware of these differences in historical understanding. Furthermore, I also found myself more and more at a disadvantage in my professional endeavors to advocate for and defend US interests and policies, as I was starting out with a different base of knowledge than my counterparts. Pushback from my exchanges would occur with a lesson in history that, because of my own ignorance, was hard to counter.

As I reflected on my career, I noticed that this historical gap manifested itself differently in the various countries where I served. In South Africa, for example, I tended to graft my history onto theirs. In Canada, I accepted that I simply did not know. In Mexico, the resentment against the history of American involvement was as fresh to Mexicans as it was shocking to me to learn.

In order to delve more deeply into this phenomenon, I resolved to pursue an advanced degree in history. I applied to the graduate history program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, which has a focus on public history, that niche of academic history concerned with conveying historical knowledge to a broad public. The areas of concentration in writing, preservation, museums, digital history, and archives paralleled traditional academic classwork and research.

When David Glassberg introduced the interplay between memory and history through the alluringly different lenses of Remembering Ahanagran by Richard White and Confederates in the Attic by Tony Horowitz, I knew I had found the path to unearthing my puzzling experiences with history abroad. John Higginson expanded this with the reading of Silencing History, Michel-Rolph Trouillots analysis of history denial in Haiti. The idea of a book came in a writing class with Marla Miller, and my two workshop colleagues, Amy Braimeier and Trent Masiki, gave the first real encouragement to going through with the whole project. What follows bears the prints of other UMass academics, including the immigration and colonization research of Jos Hernndez, the study of the foreign interventions of the United States under the tutelage of Chris Appy, and the careful mentoring of Mark Hamin on my thesis.

The case studies from my twenty-six years in the Foreign Service flowed easily. Harder, but more rewarding, was delving into the histories that I ought to have known as I maneuvered through these foreign interactions years earlier. Studying the history after the fact helped me appreciate what I had missed. I was not alone, though. The veteran career diplomat Bill Burns, who retired as deputy secretary of the State Department, noted in his memoir: There is no playbook or operating manual in the Foreign Service, and the absence of diplomatic doctrine, or even systematic case studies, has been a long-standing weakness of the State Department.