Contents

About the Author

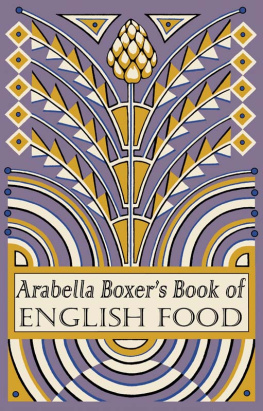

Clarissa Dickson Wright found fame alongside Jennifer Paterson as one half of the much-loved TV cooking partnership Two Fat Ladies. Her autobiography, Spilling the Beans, was a Sunday Times number one bestseller and she is also the author of many other books, including Clarissa and the Countryman, Clarissa and the Countryman Sally Forth, The Game Cookbook and Potty! She has made several programmes for television about food history, including Clarissa and the Kings Cookbook (which looks at recipes from the reign of Richard II) and a documentary on the eighteenth-century food writer Hannah Glasse.

About the Book

In this major new history of English food, Clarissa Dickson Wright takes the reader on a journey from the time of the Second Crusade and the feasts of medieval kings to the cuisine both good and bad of the present day. She looks at the shifting influences on the national diet as new ideas and ingredients have arrived, and immigrant communities have made their contribution to the life of the country. She evokes lost worlds of open fires and ice houses, of constant pickling and preserving, and of manchet loaves and curly-coated pigs. And she tells the stories of the chefs, cookery book writers, gourmets and gluttons who have shaped public taste, from the salad-loving Catherine of Aragon to the foodies of today. Above all, she gives a vivid sense of what it was like to sit down to the meals of previous ages, whether an eighteenth-century labourers breakfast or a twelve-course Victorian banquet or a lunch out during the Second World War.

Insightful and entertaining by turns, this is a magnificent tour of nearly a thousand years of English cuisine, peppered with surprises and seasoned with Clarissa Dickson Wrights characteristic wit.

A History of English Food

Clarissa Dickson Wright

CHAPTER 1

Bacon and New-laid Eggs

The Medieval Larder

A HISTORY OF English food could very well start in Anglo-Saxon times, or possibly the Roman period, or arguably even earlier, but I have elected to begin my journey in the mid twelfth century. The date may seem a little arbitrary, but I think the 1150s and 1160s were a significant moment in our culinary history, for they were the decades that started to see major developments in what we ate and the way we ate it. And there were two simple reasons for this: peace and wealth. This was a time of relative tranquillity: Henry Fitz-Empresss enthronement as Henry II in 1154 ended years of civil war between his mother Matilda, only surviving daughter of Henry I, and her cousin Stephen. As for wealth, Henry ruled an empire that included Normandy and Anjou as well as England. Moreover, England at this time was governed by dynamic and stylish people: Henrys reign wasnt without its problems, but he had all the energy and intelligence you could wish for in a ruler and he was married to one of the most stylish and influential women ever to have lived the beautiful Eleanor of Aquitaine, who also happened to be the richest woman in Europe.

England during this period was, of course, a feudal country. Loyalty was to your lord, not to your country. Tenure of property descended in established order from the Crown (who owned all the land), through the great nobles to the minor lords and knights, and down eventually to the peasants who worked the land and turned out to fight for their landlords as and when required. Everyone derived seisin, or possession of land, from someone else, and it was in the interests of the overlord to ensure that his labour was housed and fed. At the same time the power of community created an interdependence where everyone had their place and had to pull their weight for the good of all. This meant that the basics of life were generally provided. Ariadne, a thirteen-year-old friend of mine, once asked me what homeless people ate at this time, and it struck me that the homeless didnt really exist then. Yes, there were outlaws who lived in the forest for various reasons, mostly to do with evading the law (hence their name), but even they tended to band together to make life easier. The fact is that labour was a valuable asset, not to be wasted or starved. This became even more the case in the mid fourteenth century when over a third of the population was wiped out by the Black Death.

To an extent, the Church stood apart from this feudal culture. Its primary allegiance was to the Pope, not to the king, and it wielded huge power, holding dominion over peoples souls and with the power of anathema and excommunication that could refuse baptism, marriage, absolution of sins and funeral rights, and consign men to hell. Yet it was also deeply embedded in society, providing home and food not just for monks and friars but many lay brothers. It was, moreover, a substantial employer. As we will see later, once the Churchs control was shattered by the Reformation, homelessness erupted.

Another group that lay a little outside feudal society was that of the steadily growing livery companies and guilds of the nations cities, which controlled the governance of trades, from goldsmiths to butchers and street cleaners. They too, however, had responsibility for employment and so for the individuals welfare. Towns and cities at this time were small affairs. Of the 2 million people who lived in England at the time the Domesday Book was compiled in the late eleventh century, perhaps only 10 per cent could describe themselves as urban dwellers. Winchester, the second largest city in the country, had a population of probably no more than 6,000. Norwich, York and Lincoln contained perhaps 5,000 inhabitants each. As for London, described proudly by William FitzStephen in the late 1170s as head and shoulders above other cities in the world, this could boast around 10,000 citizens a handful less than the population of, say, Cranleigh in Surrey today. Nevertheless, towns and cities continued to expand throughout the Middle Ages to become major centres of trade and wealth.

I will talk about the ways in which the national diet developed during Henry IIs reign a little later. For the moment, lets focus on the basics: the staple fare that people in medieval England would have had access to. For most, that meant only what could be grown or reared locally and what happened to be in season. Opportunities to buy food from further afield would have been few and far between and well outside the budget of most. For the wealthy, things were a little different. The king and the great lords would move around the country from estate to estate so as not to devour all the provisions in one place. Their households, from the highest born to the lowliest scullions, would move with them, so being assured of their next meal. It must have been quite a sight: up to several hundred people making their way along the inadequate roads to the next place of sojourn, their ox carts creaking with everything needed for the journey carpets, wall hangings, cooking pots under cloths waxed against the rain and secured with rope. Nevertheless, the basic building blocks of their diet, like everyone elses, were seasonal, except where food could be preserved by salting, drying and preserving in fat, oil or wine.

Much reliance was placed on the living larder after all, food was much fresher if you kept it alive until the last moment, rather as they do in Far Eastern markets today. Many of the animals used for food were indigenous, but the Normans were responsible for some important additions. Indeed, their powerful impact on the food of this country can be traced through language: the names of the various animals that were eaten were transformed at the moment of death and preparation for the table from Old English to Norman French, a bullock becoming beef, a sheep becoming mutton, pig becoming pork, a deer, venison, and so on.

Next page