STILLBORN CRUSADE

ILVA SOMIN

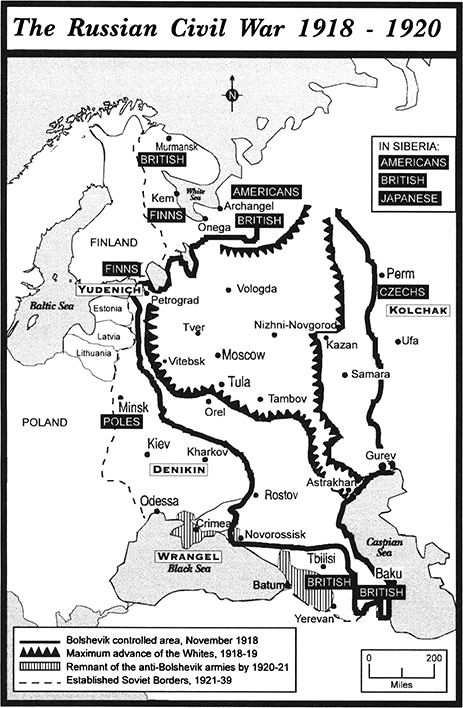

STILLBORN

CRUSADE

THE

Tragic Failure of

Western Intervention

IN THE

Russian Civil War

1918 - 1920

First published 1996 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon 0X14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor and Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1996 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 96-13273

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Somin, Ilya.

Stillborn crusade : the tragic failure of Western intervention in the Russian Civil War, 1918-20 / Ilya Somin.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-56000-274-3 (alk. paper)

1. Soviet UnionHistoryAllied intervention, 1918-1920. I. Title. DK265.4.S66 1996

947.084Tdc20 96-13273

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-1-56000-274-1 (hbk)

Contents

To my parents,

Yefim and Sofya Somin

for everything

Many people helped to bring this project to fruition. I would especially like to thank my thesis advisor, Professor N. Gordon Levin, with whom I first conceived of this topic. Professor Levin's help and encouragement have been invaluable, both in the writing of the present work and generally throughout my time at Amherst.

I also owe a great debt to Professor Peter Czap and Professor William Taubman, who generously agreed to fill in as advisors during the spring 1995 semester, when Professor Levin was on leave, and who also served as readers. Their insightful comments and criticisms have led to numerous improvements in both the style and the content of Stillborn Crusade.

Professor Paul Hollander of the University of Massachusetts, and Dr. Constantine Pleshakov of the Institute of USA and Canada Studies (Moscow), kindly took the time to read the manuscript and made useful suggestions. Christopher Gabriel of the Federalist Society provided me with a copy of his unpublished Oxford University M. Phil, thesis on Colonel Edward M. House and generally helped to impress upon me the surprising extent to which House was able to dominate President Wilson's attention to the exclusion of other advisers. At Amherst, Professor Hadley Arkes gave me the benefit of his expertise in the moral theory of intervention and reviewed the section of devoted to the application of that theory to the case of the Russian Civil War. D. Daniel Sokol read the entire manuscript and offered helpful advice on various points, an invaluable service he has performed for countless Amherst College History Department thesis writers over the last three years. Along with Michael Rubin, who also took the time to read large portions of the manuscript, Danny conducted a mock thesis defense for me that helped clarify my thinking on a number of issues.

While each of the above has helped correct flaws in my analysis, all of the opinions expressed herein are solely my own, as are any errors of whatever kind.

For their support and understanding during difficult times, I would like to thank all my friends at Amherst.

My mother, Sofya Somin, graciously took time out from her busy schedule to print out the numerous copies of the manuscript that I needed. For all their love and understanding, my greatest debt is to her and to my father, Yefim Somin. The dedication after the title page is but an inadequate expression of all I owe to them.

Amherst College

May 1995

1

Introduction

We have fought to make the world safe for democracy. Does that mean that it shall be safe for democracy everywhere but in Russia?

New York Times, June 30, 1919

[T]he great Allied Powers will, each of them and all of them, learn to rue the fact that they could not take more decided and more united action to crush the Bolshevik peril before it had grown too strong.

Winston Churchill, February 14, 1920

The triumph of the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War was the first great crack in the system of international relations established by the victorious Allies at the end of World War I. As Winston Churchill and a few other farsighted statesmen had foreseen, this event placed the entire Versailles arrangement in jeopardy almost before it had begun to function. A system based on the enforcement of shared liberal values through the League of Nations and other multilateral arrangements could not easily function effectively if one of the most powerful European states was led by a political movement that not only rejected those values but openly proclaimed its intention to actively undermine them.

Besides pursuing aggressive foreign policies of its own, the emergence of a totalitarian, anti-Western Russia would eventually help stimulate the rise of totalitarian movements of a different ideological stripe but equally aggressive foreign policy orientation in Germany and Italy. Had the Bolsheviks been defeated in the Russian Civil War, it is quite possible that Hitler and Mussolini might never even have come to power, and, if they had, it would have been far easier to establish a common Western-Russian front against them had Russia been under the rule of almost any regime other than the Soviet.

Both Hitler and Mussolini, as they openly admitted, owed much to Lenin's example. More concretely, both Hitler and Mussolini benefited from the division among their opponents engendered by the presence of Moscow-controlled Communist parties more interested in combating liberals and social democrats than fascists and Nazis.

Along with the baneful effects of the Bolshevik victory on the development of world politics, we must also consider the more immediate consequences of their victory for Russia itself. A long debate has raged between those who believe that Lenin's vision of communism was betrayed by Stalin and those who see Stalin's policies as logical outgrowths of Leninism. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, not surprisingly, several powerful new studies have reasserted the latter position.

In addition to these vast losses, Robert Conquest, the leading scholar of the Soviet regime's crimes, has estimated that some 200,000 political executions took place during the first six years of Soviet rule in Russia (1917-23), and hundreds of thousands more died as a result of mistreatment in prisons and concentration camps.

The crimes of the Lenin era alone, not to mention those of the Stalinist period that flowed from it, greatly outweighed the putative benefits Soviet rule brought to selected portions of the Russian population. Like any other great social transformation, the advent of communism raised new people to positions of authority, thus making these rising elites better off than they were before, in some cases dramatically so. This upward mobility, has sometimes been used to put a relatively favorable gloss on early Soviet rule. Yet similar gains could be cited for the early years of Nazi rule in Germany, a fact which has somehow failed to improve that regime's image among Western intellectuals. Moreover, many of these people might have done equally well or better under any of a number of possible alternative regimes. The evils of Soviet totalitarianism, like those of the Nazi variant, cannot be excused on the grounds that this regime could hardly help but benefit at least a few people.