Acknowledgments

The central puzzle of this book is the fact that ideological enemies, or states that are dedicated to opposing ways of ordering domestic politics, are sometimes willing to set aside their differences and ally against shared threats and sometimes they are not. Liberal Britain and France allied with czarist Russia against Germany in the decades before World War I but opposed allying with communist Soviet Union against Germany before World War II. The shahs Iran allied with liberal United States against the Soviet Union during the Cold War, but Islamist Iran chose not to ally with the Soviet Union against the United States after the last became an enemy after the 1979 revolution. Communist China at the end of the 1970s allied with the United States against the Soviet Union, but authoritarian Russia today has shown little interest in forming a similar alliance with the United States to balance a rising China.

This book endeavors to explain this variation in alliance policies in response to shared threats. It does so by identifying the conditions when the effects of ideological enmity are likely to be most and least salient to decision-making.

I am deeply indebted to a number of colleagues who read part or all of the manuscript and provided numerous insightful suggestions for improvement. They include Cliff Bob, Tim Crawford, Steven David, Robert Freedman, Greg Gause, Harry Harding, Morgan Kaplan, David Lesch, Henry Nau, Chad Nelson, John Owen, Binnur zkeeci-Taner, Mike Poznansky, Evan Resnick, Robert Ross, Jennie Schulze, Gktu Snmez, Frederick Teiwes, Umut Uzer, Will Walldorf, Yafeng Xia, Keren Yarhi-Milo, and Andrew Yeo. I presented portions of the book and its argument at colloquiums at Brigham Young University, Cornell University, Dartmouth College, Johns Hopkins University, and Waseda University (Tokyo). I am grateful to the participants in all these events for their input.

A portion of the evidence in chapter 4 was presented in The Rise and Fall of the Turkish-Israeli Alliance, in Israel under Netanyahu: Domestic Politics and Foreign Policy, ed. Robert O. Freedman (London: Routledge, 2020). I thank Routledge for permission to present the material here. An abridged version of the argument and part of the evidence from chapter 2 was presented in When Do Ideological Enemies Ally?, International Security 46, no. 1 (2021): 104146.

I also thank the anonymous reviewers for Cornell University Press, especially the series editor (later revealed to be Alex Downes), for their deep engagement with the manuscript. The final product benefited tremendously from their numerous insights and suggestions. Michael McGandy and Roger Hayden at the press also provided valuable advice and encouragement.

I am grateful for fellowships from the Earhart Foundation of Ann Arbor, Michigan, with the shepherding of Montgomery Brown, and from Duquesne University (a presidential fellowship). Colleagues at Duquesne at all levels have been extremely supportive of my research, and I am thankful for their aid and the productive environment they have created. The university in 2017 appointed me the Raymond J. Kelley Endowed Chair in International Relations, and I remain extremely honored by this award. I thank in particular Cliff Bob and Jennie Schulze, deans Jim Swindal and Kristine Blair, provosts Timothy Austin and David Dausey, and President Ken Gormley.

I am particularly indebted to Henry Nau, John Owen, and Steve Walt. Henry provided the most extensive feedback of any colleague. He has also been throughout my career a constant source of support and encouragement, for which I will always be grateful. John was a member of my dissertation committee at the University of Virginia over two decades ago, and I was Steves research and teaching assistant while a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University in the early 2000s. Their work, along with Henrys, continues to inspire and inform. This book, which is at heart one of ideologies, threat, and alliances, builds on the foundations that their scholarship has created.

My deepest gratitude, as always, goes to my family. I have been blessed with a large extended family, all members of which have enriched my life. A few individuals, though, deserve special recognition. I thank my Aunt Trudy and Uncle John for their constant love and support; my brother, Kurt, and sister-in-law, Deedee, for always taking an interest in my work and for their encouragement; and my in-laws, Dotty and Dan Roosevelt, for providing a welcoming home to visit and a place of laughter and fun. My mother, Lorraine, has supported me in ways beyond counting. She is my model of love. My mother along with my late father, Carl, created a home filled with love that inspired service and achievement. My greatest joys are my three children, Katie, Abby, and Will. I cannot express how much happiness they have brought to my life, and it has been my great privilege to watch them (all too quickly) grow and mature. I dedicate the book to my wife, Margaret. She is an amazing spouse and mother, and I rely on her in more ways than I know. I am blessed to have her as my partner in our journey together.

APPENDIX A

Summary of the Relationships between Configurations of Ideological Distances and the Likelihood of Frenemy Alliances

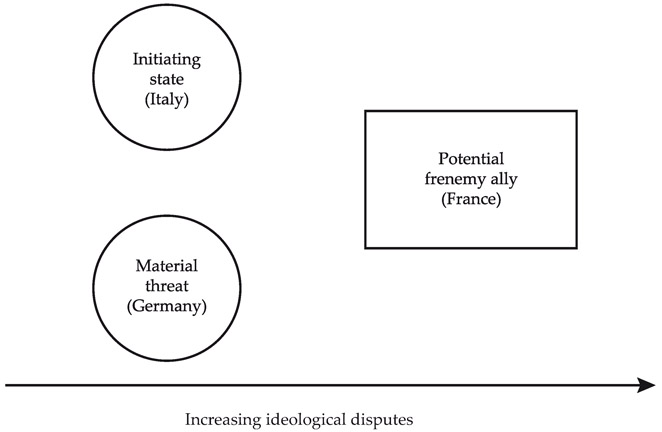

The material incentives in all the configurations are identical. The material threat is pushing the initiating state to ally with a potential frenemy ally. In the figures below, different geometric shapes indicate ideological enmity among states. Identical geometric shapes indicate high ideological similarities. I have included within each set of geometric shapes the names of the initiating state, its potential frenemy ally, and their shared material threat that were used in the highlighted example for each configuration.

Ideological Betrayal: A Frenemy Alliance against an Ideologically Similar State (Inhibits Alliance)

Core dynamic: The initiating state is being pushed for realist reasons to ally with an ideological enemy (the potential frenemy ally) against a state (the material threat) that is ideologically similar to the initiating state.

Example: Fascist Italys (the initiating states) relations in the 1930s with liberal France (the potential frenemy ally) against fascist Germany (the shared material threat).

Predicted outcome for the initiating state: Decreased preference for frenemy alliances.

Rationale: In order for the initiating states leaders to form a frenemy coalition in this situation, they must set aside two sets of ideology-based incentives: the repellent forces created by ideological differences with the potential frenemy ally and the attractive forces created by ideological similarities with the material threat. The initiating state in this configuration is also susceptible to ideological wedging policies by the material threat based on appeals to ideological solidarity and mutual enmity to a shared ideological threat.

Figure A.1. A graphic representation of ideological betrayal.

Helps explain: Why Italy did not ally with France against Germany in the 1930s; why Islamist leaders in Turkey in the late 2000s did not preserve the alliance with Zionist Israel (the frenemy ally) against Islamist Iran (the material threat) (see chapter 4).

Divided Threats: A Frenemy Alliance against a Lesser Ideological Enemy (Inhibits Alliance)

Core dynamic: The initiating state is being pushed for realist reasons to ally with one ideological enemy (the potential frenemy ally) against another ideological enemy (the material threat), but the initiating state has more in common ideologically with the material threat. The material threat is a lesser ideological enemy, the potential frenemy ally a greater one. The initiating states greatest material and ideological dangers thus diverge.