William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

HarperCollinsPublishers

1st Floor, Watermarque Building, Ringsend Road

Dublin 4, Ireland

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2022

Copyright Edward Wilson-Lee 2022

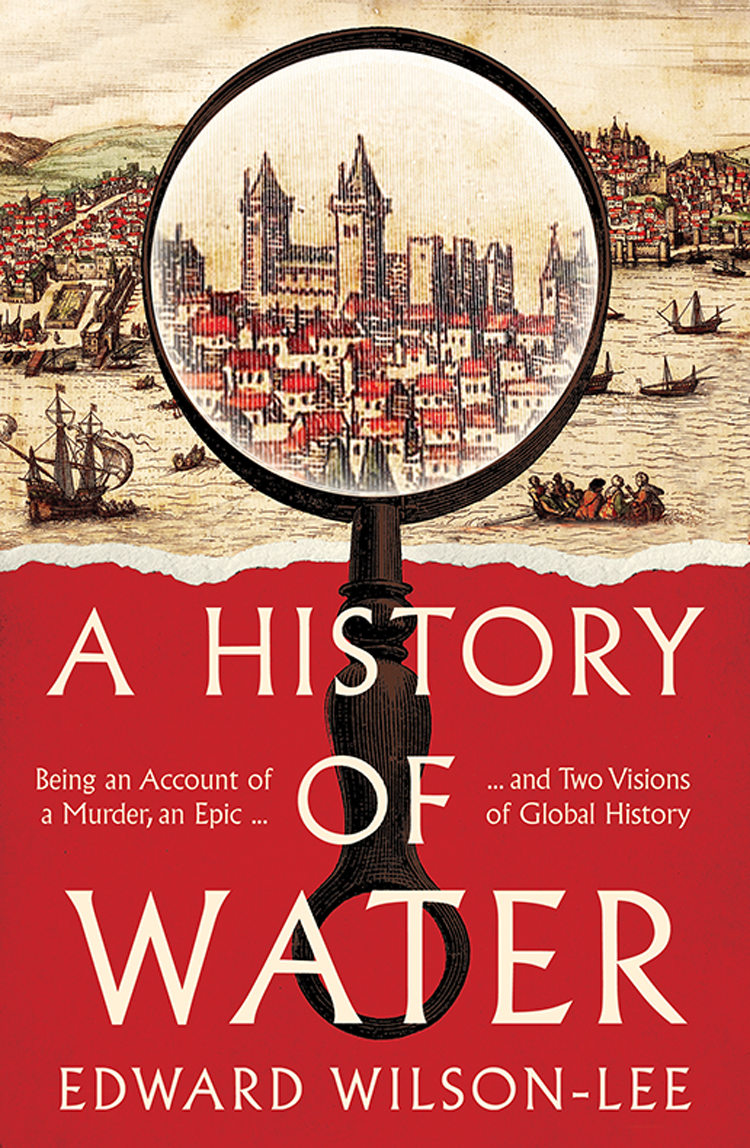

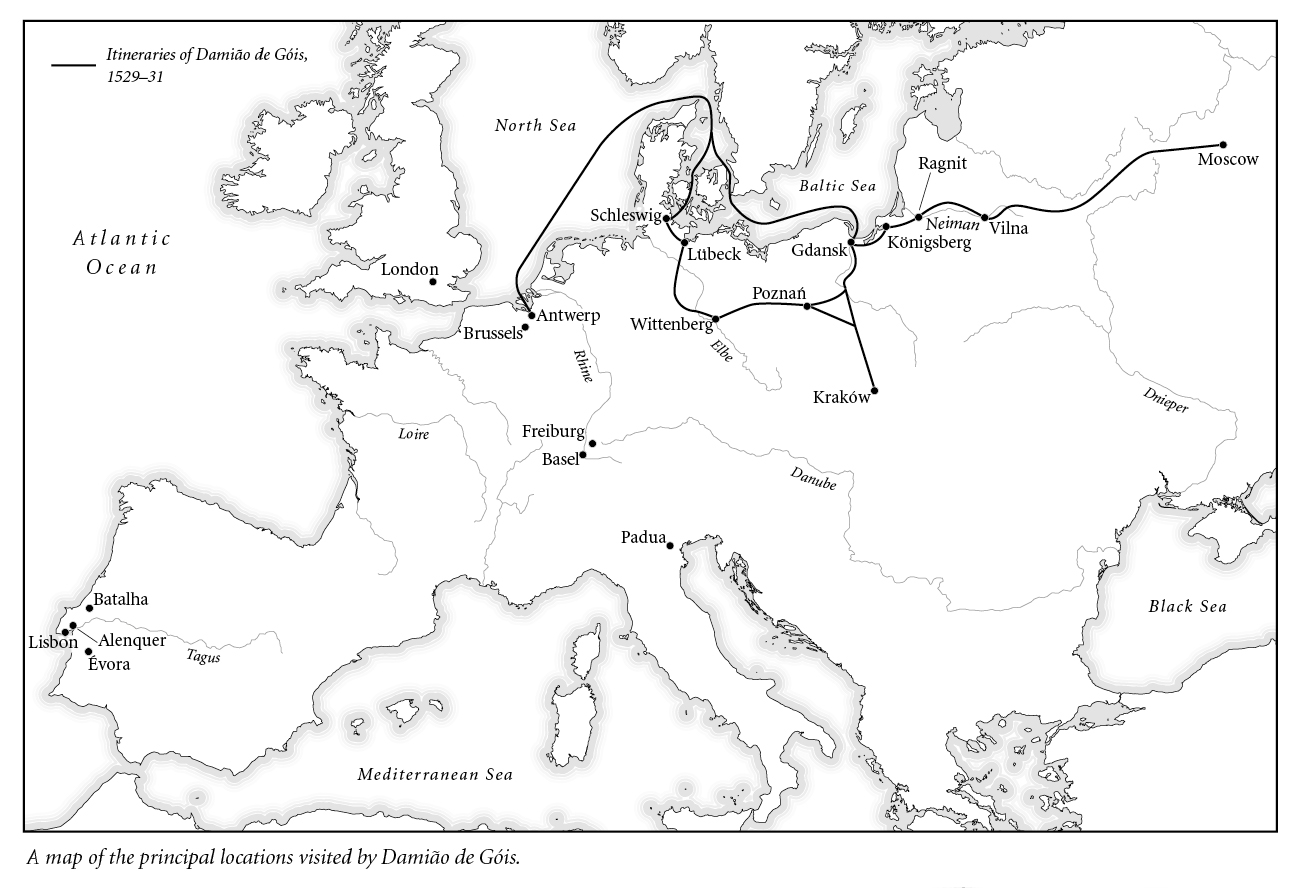

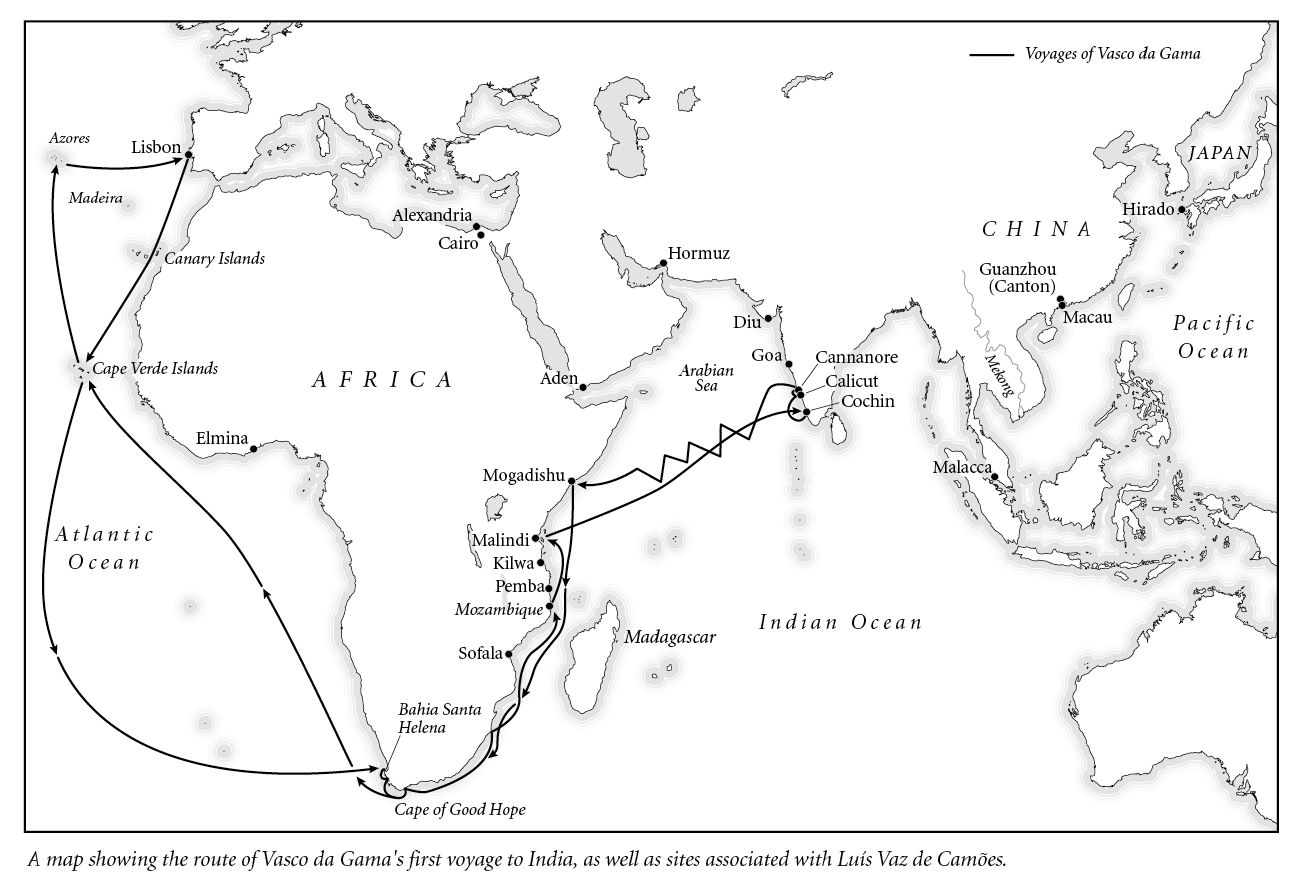

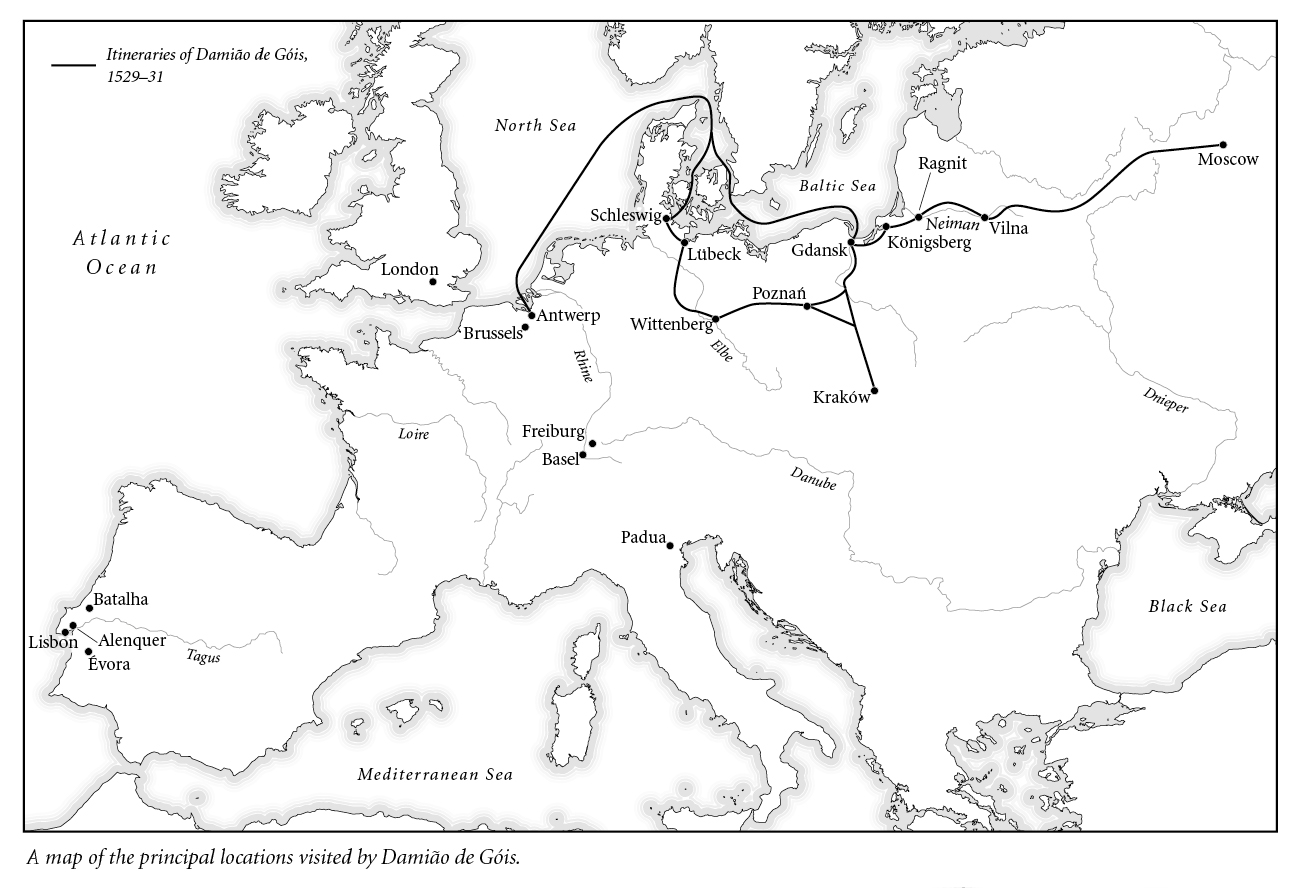

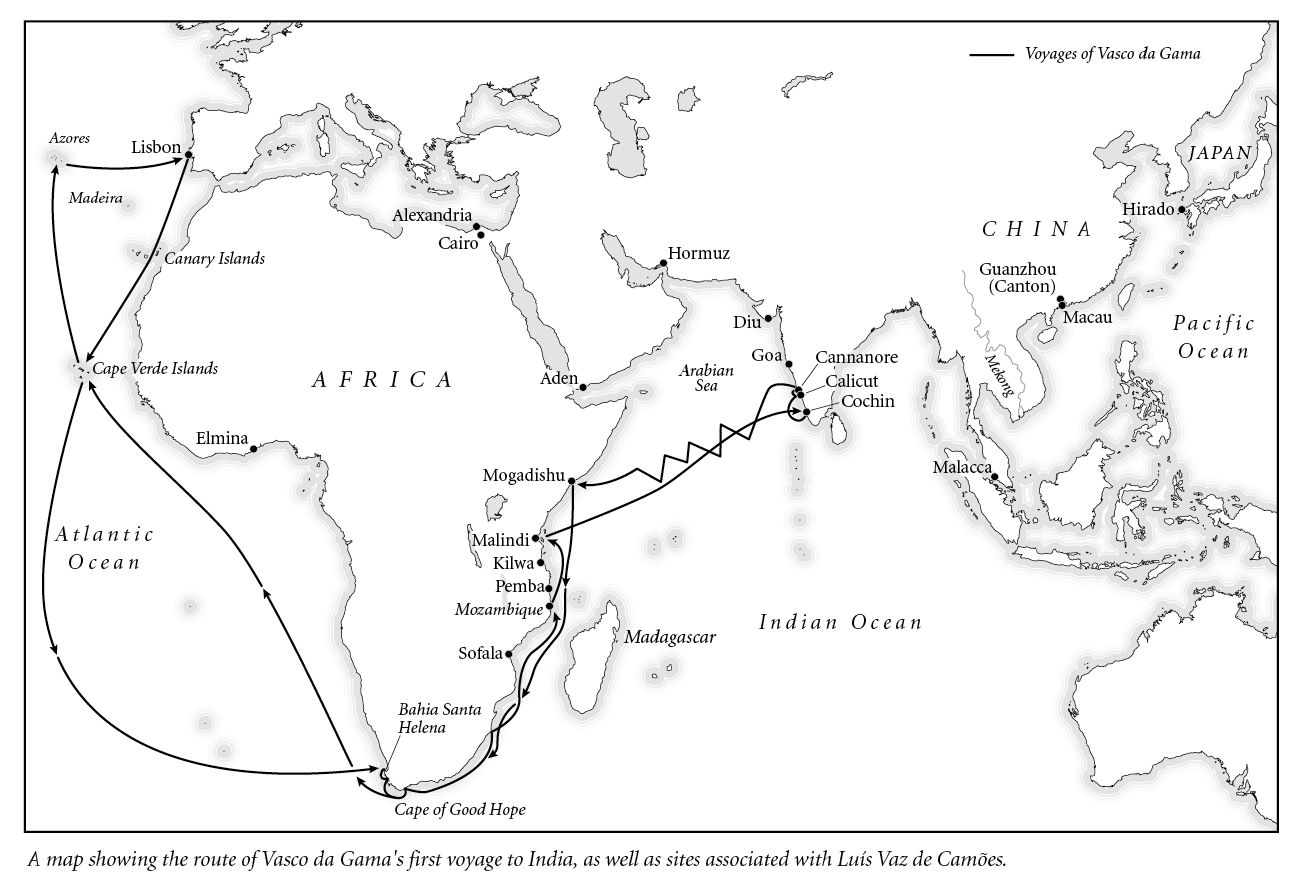

Maps by Martin Brown

Cover images Album/Alamy (view of Lisbon and Tagus River); ilbusca/Getty (magnifying glass)

Cover design by Emma Pidsley

Edward Wilson-Lee asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Information on previously published material appears

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008358228

Ebook Edition August 2022 ISBN: 9780008358235

Version: 2022-06-16

For Gabriel and Ambrose

descifradores

Following early modern practice, I have used italics in this text to represent direct quotations, the source for which can be found in the endnotes.

The tilde (, , etc.) found in many Portuguese words represents an n that was once part of the word but which is no longer pronounced. The effect is that of someone beginning to pronounce an n but then thinking better of it and carrying on, such that the name Damio (equivalent to Damian) rhymes with meow.

I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to the men of skill: but time and chance happeneth to them all.

ECCLESIASTES 9.11

When the ship parts from the quay

And feels again the space that opens

Between the ship and quay

A fresh pain comes over me I dont know why,

A mist-bank of regret

Which shines in the sun of my reawakened pain

Like the first window on which the dawn breaks

And engulfs me like the memory of someone else

Who was mysteriously mine.

LVARO DE CAMPOS , Ode Martima

Some say that the soul is mixed in the whole universe. Perhaps that is why Thales thought that everything was full of gods.

ARISTOTLE , On the Soul, trans. Kirk & Raven

All mankind is of one author, and is one volume; when one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language; and every chapter must be so translated; God employs several translators; some pieces are translated by age, some by sickness, some by war, some by justice; but Gods hand is in every translation, and his hand shall bind up all our scattered leaves again for that library where every book shall lie open to one another.

JOHN DONNE , Devotions upon Emergent Occasions

I

It was in the last days of January 1574 that Damio de Gis began his slow transformation into paper. This ending would not, perhaps, have come as a particular surprise to a man who had spent his life among documents, as Guarda-mor in charge of the Portuguese royal archive. He was entered into the register of his parish church in the village of Alenquer, a half-days journey from Lisbon, the sacristans split-quill pen catching on the fibrous paper as he wrote that on the thirtieth day of the month of January of the year 1574 Damio de Gis died and was buried in the chapel of this church. The sacristan added further, underlining the words that note an unusually quick burial, that in truth it was the same day and month and year as above. It is fortunate that the register is so exact about the timings, as the tombstone Damio had commissioned for his own burial was wrong gave a date, in fact, of more than a decade earlier. Many have looked for the body that was buried that day without success, and what remains of Damio de Gis is only paper: as well as the entry in the church register, he was folded into a letter that made its way to northern Europe with an account of his death, dispersed across Europe in unnumbered signed copies, found crumpled into a notebook that was discovered in the Lisbon archive some 200 years later. These documents may explain the sacristans muted alarm, as a number of them suggest that the kings archivist was the victim of a most peculiar murder.

The pieces of Damios death do not match up. One of the accounts suggests that he was stopping at an inn on the last night of his life, and that at the end of the evening he had sent his servants to bed, himself staying up next to the fire to ward off the midwinter cold and reading a certain piece of paper. Then something transpired in the illegible night. The report says that his body was found burned the next morning, though the description glances aside from the macabre scene to note that he was still clutching part of the same piece of paper he had been reading the night before, even if the rest of it had been consumed by the flames. The body is at the centre of the scene, holding all else around it in suspense with the newness of it being a mere object; yet it was the curious survival of the paper that caught the observers attention, less fragile (it seems) than Damios life. The report hesitates to say for sure what had taken place, when the shadows were dancing like moths at the edge of the fire, with the spit and pop of the wood, in the sough of the nights expanse. Instead, the testimony speculates that this undoing came either from falling asleep or some incident that deprived him of his senses. A slightly later anecdote also records his death by burns to his face and chest, head and arms, and suggests that his end significantly coincided with a day of auto-da-f in Lisbon, the fires in which heretics were burned.

A third report does not mention the fire at all, and in fact suggests that Damios death took place at home. But it is also less cautious in its explanation of the events. While it allows for the possibility that the archivist may have died of apoplexy a contemporary term for stroke or other sudden death it proposes that he may rather have been killed by thieving servants, using the Latin term suffocatus, which can mean either strangled or drowned.

Clues regarding the events of that January night are scattered across archives in Lisbon, Antwerp, Rome, Venice and Goa, pieces of a man whose life was tied up with records. The archive Damio himself oversaw was barricaded inside a tower of Lisbons hilltop Castelo de So Jorge, a site that had been Roman and then Arabic and then the stronghold of the Portuguese crown, though it had now largely been abandoned by the court, as the royal family preferred to live in the more modern riverside palace. Damio lived only a short distance from this Torre do Tombo Tower of Records in apartments that overlooked the Casa do Esprito Santo where residents of the castle attended church services. The building in which he lived no longer stands, having like much of Lisbon succumbed to the violent earthquake that shattered the city in 1755 and the series of fires and tidal waves that followed. But the tower itself remains, now empty but once the storehouse of Portugals memory, a darkened chamber in which all the secrets of the kingdom were kept. To those unfamiliar with the archive, it might well have seemed no more than a farrago of mouldering papers; but this puzzle box, in which each document could spring a lock or lead to a dead end, offered enormous power to those who knew its technique. The legends of China and Vietnam, cultures that Europe was encountering for the first time during Damios youth, are filled with archivists who can change a persons fate by cancelling half a line in the right ledger, and the Torre do Tombo was exactly the place where such witchcraft could occur.